Quick: what’s the highest-grossing movie at the U.S. box office so far this year?

Even if you’re only a casual film fan, you probably guessed either Black Panther or Avengers: Infinity War. After all, Marvel movies are always a safe bet at the box office.

(In fact, you can probably guess “the latest Marvel or Star Wars movie” is the answer to this question no matter what year you’re reading this.)

Well, as I type, Black Panther has a slight lead but A:IW isn’t far behind. What’s even more impressive that they’re both already among the All-Time Top 10 Highest-Grossing Movies in the entire history of Hollywood… and they’ve only been in theaters for a few months.

Incredible, right?

But things weren’t always this way.

In fact, the box office supremacy of superhero movies is a very recent development.

Even more astounding are the ever-growing domestic and global tallies that films of all genres are earning around the world, as new box office records seem to be broken every month.

In short, box office totals just keep rising, even as fewer people actually go to the movies.

But wait… how is that possible?

And how did we all get so obsessed with tracking every film’s bottom line in the first place?

Would you believe it all started with an X-rated movie?

Here’s a brief look at the surprising history of how movie box office works, and why the numbers are never really what they seem.

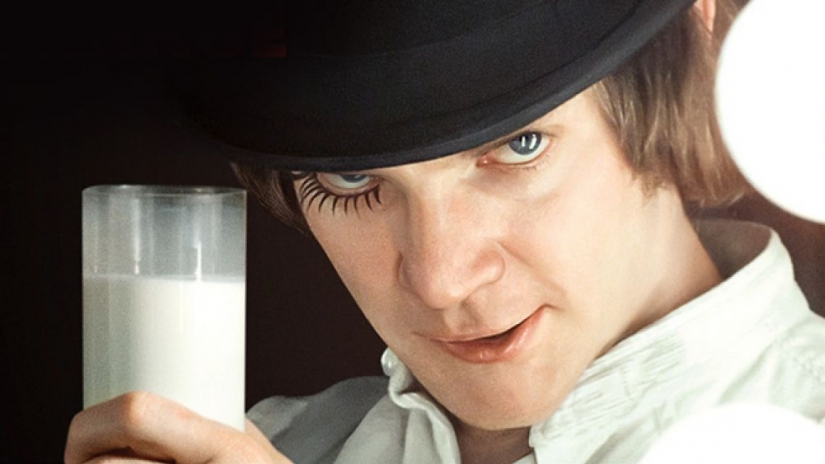

Stanley Kubrick Invented Modern Box Office Reporting

I was cured, all right

Given how breathlessly most news and media outlets report each weekend’s box office totals, it’s hard to imagine that there was ever a time when the average American had no idea how much money a film had made at the box office.

But what we think of as modern box office reporting began in 1971, when director Stanley Kubrick took the marketing of his new X-rated film A Clockwork Orange into his own hands.

As Kubrick’s colleague Mike Kaplan recalls:

Clockwork would be shown in standard cinemas as a quality platform release, which meant there were many options per city. I knew that Don Rugoff’s Cinema 1, the most prestigious cinema in New York, had to be the New York theater [for Clockwork’s debut] but how to be sure that the film would be booked into the best cinema in Indianapolis or Cleveland or Atlanta? To choose the right theater in each city, we needed to know which cinema sold the most tickets to the most interesting pictures. But while a studio would know what its own films grossed, detailed box-office figures of competitive films were closely held secrets. There was no comparative information, and that is exactly what Stanley wanted.

So Kubrick, Kaplan, and their secretary Maureen hatched a plan: they gathered up the last 18 months’ worth of the film trade publication Variety and crafted a custom box-office tracking database by hand.

The information in Variety included the weekly gross for every theater, plus the previous week’s ticket sales from whatever film had played, as well as seating capacity and ticket prices.

With all this data, Kubrick could compare the numbers among all theaters in a region and determine which theater in every city was most likely to have a successful release of a challenging (and borderline pornographic) film like A Clockwork Orange.

Once they crunched the numbers, Kubrick and his team worked out the film’s release strategy with Leo Greenfield, the vice-president of distribution at Warner Bros, who was stunned by Kubrick’s level of detail.

The results?

A Clockwork Orange opened to stellar reviews and broke theatrical records in nearly every major American city, becoming a highly-influential cult classic in the process.

But its influence didn’t end onscreen. When Hollywood saw the numbers that Clockwork was putting up, they asked Kubrick how he did it. Somewhat surprisingly for a well-known control freak, Kubrick told them.

And with that knowledge in hand, every studio was off on a race to dominate box office headlines.

Coppola, Spielberg, and Lucas Break the System

They made us an offer we couldn’t refuse

Blame The Godfather.

In the 1970s, the “film school generation” of Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, and other American auteurs changed Hollywood from a studio-based production model where producers and executives controlled the final product into a director-driven model where a recognizable name and a one-of-a-kind vision could earn you final cut.

But that change would never have happened if their movies weren’t breaking all previous box office records.

It started in 1972, when Francis Ford Coppola‘s The Godfather became the first movie to ever gross $100 million at the U.S. box office. Once studios realized that breaking $100 million was possible, they started looking for ways to get there even faster.

In 1975, Universal found a way.

We’re gonna need a bigger boat

Steven Spielberg’s Jaws became the first film to ever debut in wide release, meaning it was available to view in most major American cities on the same day.

Prior to Jaws, films would debut in a small number of markets and then platform out based on box office earnings and word of mouth. That tactic is still seen today for indie, arthouse, and documentary films, but wide release is now the standard practice for mainstream blockbusters ever since Jaws destroyed box office records.

As a result, it only took Jaws six months to set the all-time domestic box office record, plus an eventual worldwide record of more than $470 million.

That seemingly untouchable title stood for only two years.

When George Lucas’s original Star Wars (now known as Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope) debuted in 1977, 20th Century Fox had such low hopes for its long-term success that it allowed Lucas to retain 40% of the film’s profits, as well as the movie’s merchandising rights.

(Maybe it had something to do with the film’s legendarily bad first edit?)

Instead, Star Wars was the biggest hit the country had ever seen, and Lucas became one of the wealthiest filmmakers of all time.

Released on May 25, 1977, Star Wars set a Memorial Day weekend record of $2.5 million despite opening on just 43 screens nationwide. By December it had claimed the domestic box office crown from Jaws, and in April of 1978 Star Wars finished its original run with a then-record box office tally of $215 million.

Impressive, no?

Now fast-forward 40 years, and you’ll find that Black Panther earned slightly more than that…

… in just 6 days.

But today’s box office records don’t mean quite what they used to, for two reasons: magic calendars and the mysteries of inflation.

Inflation Means You’re Never Getting the Real Story

“Wakanda forever!”

In 1977, the year Star Wars became a phenomenon, the average movie ticket price in America was either $2.13 or $2.23, depending on your source.

In 2017, the year Black Panther became only the 3rd movie to ever surpass Titanic in terms of domestic box office, the average movie ticket price in America was $8.97 — which is on par with national inflation over the last 40 years.

(Note that these numbers include an average of all ticket prices — regular adult tickets, matinees, 3-D, IMAX, etc.)

Wakanda’s rise to the top of the box office is notable for many reasons, but the effects of inflation can’t help but add an asterisk to the conversation.

Why Black Panther and Wakanda Are the Keys to Marvel’s Future

So, yes, box office records are designed to keep falling simply because inflation guarantees there will always be a new “all-time highest-grossing movie” every few years.

But those numbers don’t mean more people are actually seeing modern movies.

In fact, individual ticket sales have been steadily declining for decades, as television, VCRs, and the Internet compete directly with the theatrical experience.

That’s why a more accurate way to measure the all-time biggest box office hits would be to count the number of individual tickets sold, not the amount of revenue earned.

But there’s one very big problem with that method.

We’ll (Probably) Never Top Gone with the Wind

Frankly, Scarlett, I don’t give a damn about inflation

If you look at the list of all-time highest-grossing domestic box office after adjusting for inflation, you’ll see one film to rule them all: 1939’s Gone with the Wind.

At current inflation rates, GWTW has earned $1.8 billion in the United States. That’s a lofty $219M more than second-place Star Wars: A New Hope at $1.6B adjusted. (The Sound of Music comes next at $1.3B adjusted, or half a billion dollars behind GWTW.)

That’s a LOT more ticket sales.

To put this in perspective, Black Panther, whose headline-dominating domestic total of $699M (and counting) currently has it ranked #3 on the all-time domestic box office list, falls to #30 when adjusted for inflation. (Meanwhile. current #4 Titanic only falls to #5.)

That means more than 20 classic films sold an epic amount of tickets back in the day.

In fact, if you look at the all-time domestic box office adjusted for estimated ticket sales at the time, Black Panther is estimated to have sold 76 million tickets. That’s impressive, especially in this highly-competitive media climate.

But Gone with the Wind is estimated to have sold 202 million tickets, or nearly 3 times as many as Black Panther. (It’s also the only film to ever top 200M domestic tickets sold.)

While the cash totals at the box office may be going up, no one’s going to be stealing Scarlett O’Hara’s all-time ticket sales crown anytime soon.

So, instead, studios keep looking for new ways to earn box office headlines.

The $100M Opener Was Once an Impossible Dream

Face it, Tiger… You just hit the jackpot

Until 2002, no movie had ever earned $100 million on its opening weekend.

Then Sam Raimi‘s Spider-Man debuted, and Hollywood got its very first proof that a good superhero movie is basically box office catnip.

Spider-Man obliterated the opening weekend record, needing just 3 days to become the fastest film to ever earn $100M en route to an eye-opening $403M domestic total. (It also earned $418M overseas, cracking the code of superhero box office dominance that Marvel Studios has since perfected.)

Since 2002, when Spider-Man finally proved a $100M opening weekend was possible, that feat has been accomplished 51 more times. It’s now so commonplace that a $100M opening weekend is considered the industry standard for a franchise blockbuster.

The new brass ring? $200M openings.

There have been 6 of those in history, all since Marvel’s The Avengers first hit that mark in 2012. Two of them happened just this year, and if Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom reaches that goal in June, this would be the first-ever year with three different $200M openers.

But with current inflation rates, you can expect a Marvel movie to earn headlines for a $300M opening weekend soon enough.

Unfortunately, even those headlines will be slightly misleading, because…

Sometimes Thursday Is Friday

Maybe Dr. Strange can use the Time Stone to figure out how Thursday previews work

Have you ever seen a movie during Thursday night preview showings?

If so, you technically saw it on Friday, at least as far as Hollywood is concerned.

That’s because most studios roll their Thursday night preview numbers into their Friday totals.

But wait… how is that even… allowed, right?

Well, in the perpetual arms race for box office records and buzzworthy headlines, every sneaky tactic counts — and that includes reporting Thursday previews as part of Friday’s total because…

Uh…

Well, there really is no explanation, and it literally makes no sense.

But since Thursday previews can sometimes amount to as much as 20-25% of a movie’s weekend total, who wants to risk a wonky headline like Avengers: Infinity War Sets New 3-Day Opening Weekend Record [But It Actually Took 4 Days]?

Besides, at least the movie theaters must love all that extra business, right?

Well… not necessarily

Movie Theaters Rely on Concessions, Not Ticket Sales

Let’s all go to the lobby to get ourselves a treat

Wait… what?

Yeah. The whole movie business is a shell game.

See, when you buy a movie ticket, about half of that ticket price goes back to the distributor or studio. That means your local theater or multiplex is only keeping about $4.50 of that current $8.97 average ticket price.

But it gets worse.

Distributors of high-demand films like a new Marvel or Star Wars title can negotiate even higher terms. When Star Wars: The Last Jedi opened in 2017, Disney took some heat in the press for allegedly demanding 65% of the ticket price.

To be fair, this ratio is actually an improvement from past decades. In 1972, Paramount was pocketing 90 percent of every ticket sold for The Godfather.

But even looking past the guaranteed blockbusters, most distributors angle to receive the majority of each ticket sold during the first few weeks that any film is in release, because that’s when most people are inclined to go see it. This means most theaters won’t start getting a favorable return on their ticket sales split until a few weeks into a film’s run, when it’s been in theaters long enough to no longer be a big draw.

No wonder the price of popcorn keeps going up.

By comparison, around 80 cents of every dollar spent at the concession stand is direct profit for the theater. And since teens have more expendable cash to buy snacks and drinks, theaters and studios both have a vested interest in marketing PG-13 blockbusters rather than G or PG (which skew younger and encourage cheaper matinee tickets) or R-rated films (because adults are less likely to splurge on concessions).

It’s also why most theater owners didn’t complain too loudly when Disney altered the terms of the deal for those Last Jedi tickets. In 2016, The Force Awakens and Rogue One helped combine to push concession sales at the AMC Theatre chain over $1 billion.

Gone with the Wind may have sold a lot of tickets, but Star Wars sells a LOT of Milk Duds.

So that must mean a true blockbuster is always good financial news all around, right?

Alas… not always.

The 3X Rule

The cast of Solo stare up at the film’s insane break-even point

Generally speaking, a movie usually needs to earn 3 times its production budget at the worldwide box office in order to break even.

Why?

Because it costs roughly twice as much to distribute and market a film around the world as it does to produce that film in the first place.

This means if you have a film that costs $100M to make, that movie needs to earn $300M globally just to break even.

That’s one reason why Solo: A Star Wars Story was making box office headlines for all the wrong reasons. Not only did it debut to a “meager-for-Star-Wars” opening of $84M — or about $20M less than industry analysts had hoped — but the film reportedly cost Disney around $250M to produce. Right now a $750M break-even point looks like a galaxy far, far away.

(That’s too bad, since Solo is the closest Disney has come to the original spirit of Star Wars.)

Unfortunately, even when a film does make a profit, that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s considered successful… or, technically, profitable.

(Hang on, it’s about to get weird.)

Not All Profits Are Created Equal

Desperately chasing that elusive Hollywood profitability

Sure, everyone wants to be in a blockbuster. It’s good business.

But as Edward Jay Epstein explains in his book The Hollywood Economist, it’s not always a great payout.

While some actors, directors, and producers will sign contracts that include a percentage of a film’s profits, many movies never actually declare a profit no matter how much money they earn.

How is this possible?

Because the studios like to get very creative with their accounting, to ensure that they retain the lion’s share of revenues.

Granted, this isn’t surprising.

Right now, every major Hollywood film studio is owned by a publicly traded corporation (with the exception of MGM, which is currently owned by a consortium of capital management groups). This means every dollar spent or earned affects the shareholders’ bottom lines.

As such. the studios can’t afford to hand out cash to every profit participant in their production schemes, even when those films are wildly profitable. So the trick is to hide as much profit as possible inside other expenses within the marketing and distribution costs for those films, to ensure that they never technically profit enough to trigger any revenue-sharing deals.

This includes adding future marketing costs to the ledger of films that have long since left theaters, essentially burying any profits behind a perpetual smokescreen.

As result, we end up with bizarre situations like Lucasfilm claiming Return of the Jedi ($475M worldwide box office against a production budget of $32.5M) never earned a profit…

Or New Line alleging that the Lord of the Rings trilogy ($3 billion worldwide box office against a collective production budget of ~$300M) never broke even…

Or the financiers of one of the most financially successful films ever made — My Big Fat Greek Wedding ($368M worldwide box office against a production budget of $5M) — claiming the film actually lost money, all so the producers and stars would never receive their payouts.

Maybe they should all go into the popcorn business instead.

Box Office Gets the Headlines, but (Actual) Profit Keeps the Studios Alive

One of the best investments ever made

Even with our higher modern ticket prices, only seven horror movies have made over $100M so far this century.

So why does Hollywood keep making so many of them?

Well, in addition to being great date night entertainment (read: concession stand gold), horror films often star no-name actors and don’t require expensive special effects to generate their jump scares.

This is why a studio like Blumhouse (creators of the Paranormal Activity and Insidious franchises) will keep pumping out low-budget horror movies like DIY cash machines.

For example, even a critical and box office dud like The Lazarus Effect may have “only” made $38M globally, but it also only cost $3.3M to produce.

Marvel can keep their record-breaking headlines; Blumhouse will gladly take a 10X return on their investment even on their flops.

You’ll Never Guess Who the Original Low-Budget King of Hollywood Was

For all our talk of epic box office records, sometimes the most memorable numbers come from tiny films that break out in a big way.

So what was the original champion of budget-to-profit ratio?

In 1973, American Graffiti, a melancholy high school dramedy about the last night of summer, became a surprise hit that literally no one saw coming. In fact, its distributor, Universal, had such low hopes for the movie that they considered releasing it straight to TV.

Instead, on a production budget of just $777,000, American Graffiti went on to earn a staggering $115M at the domestic box office, or 148 times its money.

Adjusted for inflation, that’s $601M, which currently makes it the 49th-biggest movie of all-time.

Oh, by the way: who was the writer-director of that low-budget unicorn?

George Lucas, who wrote it on a dare from Francis Ford Coppola.

And you’ll never guess what movie he decided to make next.

Did You Enjoy This Post?

Share this post on Facebook or Twitter. (Sharing is caring, yo.)

Subscribe to my newsletter and get a weekly update I don’t share anywhere else.

1 Comment

Tim Brechlin · June 6, 2018 at 9:56 pm

A great example of fuzzy accounting is with the Star Trek franchise; while Star Trek: The Motion Picture was absolutely a financial hit for Paramount, they and their parent company Gulf + Western had absolutely no desire to deal any further with Gene Roddenberry, so they claimed the final cost was $45 million (by tacking on more than a half-decade’s worth of attempts to make a movie as well as the costs from the aborted Paramount television network and the Star Trek: Phase II series), using it as an excuse to kick him upstairs, give him an office and the title of “executive consultant,” pay him handsomely, but strip him of any further direct involvement in the Trek movies. He was allowed to see every script draft and provide his comments (and he was the person who leaked Spock’s death in The Wrath of Khan and the destruction of the Enterprise in The Search for Spock to the fanzines), but for all intents and purposes, his actual authority was ripped away. He didn’t have any control over another Trek project until he and David Gerrold approached Paramount about doing The Next Generation … at which point he was borderline-senile, his brain badly addled from decades of alcohol and drug abuse.