Every villain is the hero of his own story.

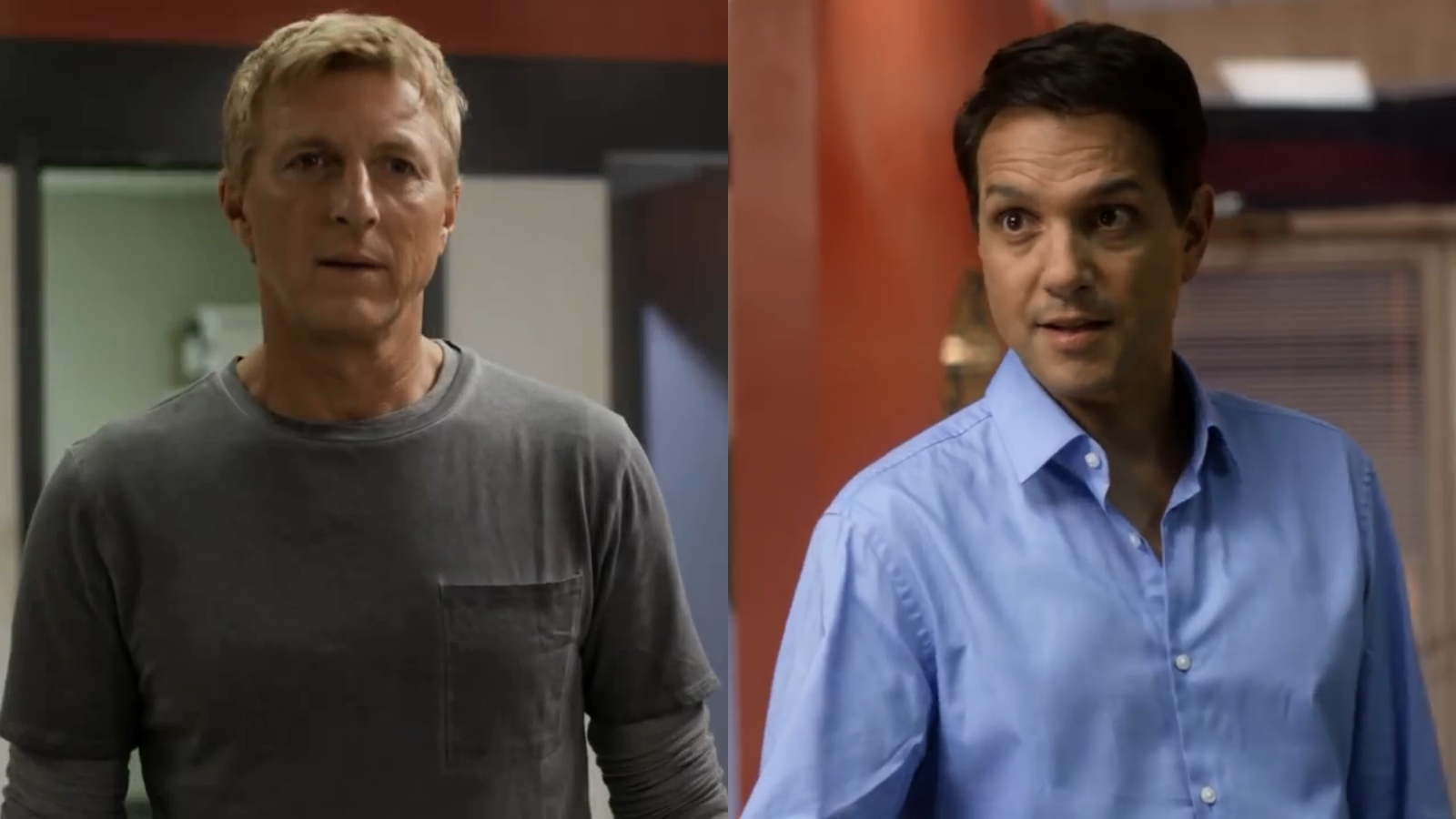

In Cobra Kai, we see this maxim come to life in the form of Johnny Lawrence (William Zabka). The former high school bully once came a single point away from winning the 1984 All-Valley Under-18 karate championships before injured underdog Daniel LaRusso (Ralph Macchio) did this:

With one well-placed crane kick, Daniel won the tournament and changed the trajectory of his and Johnny’s lives forevermore.

This moment is the climax of 1984’s original The Karate Kid movie, a cultural mega-hit that spawned three sequels and a 2010 remake. It also provides the creators of Cobra Kai — the YouTube-turned-Netflix TV sequel to the film franchise — with a perfect series setup that’s as rich in ’80s nostalgia as it is in timeless themes of identity and self-worth.

In Cobra Kai, we get to examine what happens to vanquished villains after the credits roll. We also get to ask a much deeper question: in the end, who decides if we’re the villain in someone else’s story, or the underdog hero of our own?

To find out, let’s look at what Cobra Kai does best: establishing character through conflict.

Your Characters Are What They Do (and Don’t Do)

Shows like The Wire explored the complex idea that who counts as a “hero” or “villain” depends on your perspective. Cobra Kai inverts this concept by placing us directly in the perspective of the “villain,” which makes him our “hero” by default… right?

To do this, the pilot episode of Cobra Kai functions as a very efficient “origin story” for Johnny.

The series begins by reintroducing us to 50-something Johnny Lawrence, now an alcoholic repairman and absentee father who literally lives in the constant shadow of Daniel LaRusso’s perpetual success.

Showrunners Josh Heald (Hot Tub Time Machine) and Jon Hurwitz and Hayden Schlossberg (Harold & Kumar) quickly establish everything we need to know about Johnny, including:

- the sad state of his daily life (drinking alone in his barely-furnished apartment, watching ’80s movies on an endless loop, driving a “classic” car that’s falling apart)

- his terrible job (cleaning the gutters of the wealthy while their children mock him)

- his self-destructive habits (racism, sexism, toxic masculinity, isolationist self-loathing)

- all the things he wants but doesn’t have (money, love, respect)

By contrast, Daniel LaRusso is initially seen as an omnipresent spectre in Johnny’s life, always visible in billboards and TV commercials as the owner of the most successful automotive group in the valley — a success that Johnny likely believes he could have had, if only he’d won their match 34 years ago.

By forcing us to see Daniel through Johnny’s eyes, we come to view Daniel not as a conquering hero who unquestionably deserves all of his success, but as an egotistical ham who reeks of self-satisfaction. When contrasted with Johnny’s empty life, we can’t help but feel bad for the former bully.

This sequence of early scenes establishes that Johnny’s primary antagonist isn’t actually Daniel; it’s himself. Johnny’s central conflict isn’t interpersonal; it’s his internal conflict between how he sees himself and what he thinks he deserves.

What we have here is a redemption arc.

Therefore, as viewers, it’s not that we necessarily want to see Daniel lose what he’s earned; it’s that we want to see Johnny stop losing, and to stop getting in his own way.

The problem is, Johnny sees his road to redemption differently than we might want.

The Bigger the Difference, the Bigger the Conflict

For Cobra Kai to work, it wouldn’t be enough for Johnny to simply be less successful than Daniel; they must start out as complete opposites.

This means we need to see Johnny living alone in a run-down apartment with bad plumbing, driving a burned-out Pontiac muscle car that serves as a relic of ’80s machismo, hitting on a jogger who blows him off and calls him a creep, getting fired from a job he hates, and looking so down on his luck that a homeless woman accuses him of trying to steal her turf.

By contrast, Daniel is shown as perpetually smiling, respected, and in control. In the beginning of the show’s second episode, we see him waking up in his palatial home, making breakfast for his appreciative children, bonding with his supportive wife, and having fun all day at work. It looks as though he doesn’t have a care in the world… but of course, this is impossible.

In reality, he’s worried that he’s starting to lose touch with his daughter and son — or, more specifically, that they’re growing up to be not very good people. His son is self-absorbed and entitled, and his daughter is starting to lie, get in trouble, and ignore her old friends as she tries to join the rich and popular crowd. Daniel is starting to realize that he can’t just magically wish for his kids to turn out perfect; he has to put in more work.

Meanwhile, Johnny’s own son is so estranged that when his high school principal busts him for drugs, he tells Johnny off over the phone in a blatant show of disrespect. Thus, not only are Johnny and Daniel’s financial lives drastically different, but even their parental troubles are different by an order of magnitude.

So, what provides Johnny with a chance at internal and interpersonal redemption?

The opportunity to serve as a mentor and father figure to someone else: his teenage neighbor, Miguel Diaz (Xolo Maridueña)

Character Motivation Grows from Their Low Point

One night, when Johnny can no longer ignore the sounds of Miguel getting beaten up in a parking lot by his high school bullies, he intervenes — to protect his car, not Miguel — and kicks the other kids’ asses… only to get himself arrested and spend the night in jail.

The next morning, Miguel asks if Johnny will teach him karate, but Johnny turns him down. (If you want to get all Joseph Campbell “Hero’s Journey” about it, this would be the point where our hero “refuses the call.”)

He also refuses the offer of financial stability from his stepfather Sid (Ed Asner), who cuts Johnny a check in order to write his deadbat ass out of his life for good. Johnny, still a man of pride despite appearances to the contrary, rips the check up; he doesn’t want anyone’s charity. So Sid leaves, and Johnny drinks himself into a stupor while reminiscing about flashbacks from the first two Karate Kid movies…

which leads him to drunkenly drive over to the high school where Daniel defeated him all those years ago…

and where an SUV driven by distracted rich teens now totals his beloved Pontiac in a hit-and-run.

To make matters worse, he finds out his car was towed to the place he’d never want to go:

A LaRusso dealership.

Cobra Kai: The Inciting Incident

Now Johnny is at his lowest point — and this brings him into inevitable conflict with Daniel himself.

At the dealership, Johnny does all he can to negotiate getting his car towed somewhere — anywhere — else. But just as he’s about to get that issue figured out, Daniel walks in and recognizes Johnny. Now Johnny is forced to live out his own worst nightmare: making small talk with the guy who humiliated him and ruined his life while turning Johnny’s defining failure into his own rags-to-riches success story.

Not only does Johnny end up getting embarrassed again by Daniel and his coworkers, but he also has no choice but to accept Daniel’s charity offer to cover the cost of Johnny’s car repairs himself, since the damages cost more than the car is worth. (Adding insult to injury, Johnny also realizes that Daniel’s daughter was a passenger in the SUV that totalled his Pontiac.) Now fully humiliated by the LaRusso clan, he leaves the lot with Daniel’s parting gift: a free bonsai tree, which Daniel gives to every customer as a way to honor the selfless spirit of his former sensei, Mister Miyagi (Pat Morita).

But it’s what Daniel says at the end of this conversation that provides a crucial turning point for Johnny: “It’s a good thing Cobra Kai is gone; everybody’s a lot better off now.”

These are the words that wake Johnny up, because he realizes everybody except him has been better off since Cobra Kai ended.

With that realization fresh in his mind, Johnny drops the bonsai tree — and its representation of service, holistic balance, and calming inner peace — with a crash and stalks off Daniel’s lot (to the tune of “Sirius” by The Alan Parsons Project, which was the song the Chicago Bulls used as their home court introduction theme during the unstoppable dominance of the Michael Jordan years).

This can only signal one thing in an ’80s nostalgia trip like Cobra Kai: a montage.

At home, Johnny pieces Sid’s torn check back together. He uses the money to lease space in the strip mall and open a new Cobra Kai dojo. And he signs up his first customer: Miguel. Johnny is going to redeem himself by becoming Miguel’s sensei and instilling within him the Cobra Kai motto: “Strike first. Strike hard. No mercy.”

In just 30 minutes, we’ve established the main characters, their core internal and interpersonal conflicts, and the audience’s own conflict: yes, we want Johnny to find his redemption… but not like this.

Rotting Machismo

Johnny’s initial persona in Cobra Kai represents the macho glory days of the 1980s, which haven’t aged very well in the 21st Century. He’s casually racist and sexist, perpetually self-destructive, dismissive of other people’s needs, unable to accept help when it’s offered, and he doesn’t even recycle. He repeatedly tells people that he just wants to be left alone. His social flaws and his isolationist misanthropy are presented as a benchmark of just how many changes he needs to make in order to reconnect with others and get his life together.

On the other hand, his neighbor and main student, Miguel, represents a kinder, gentler, and more self-aware social sensibility. He points out Johnny’s “gendered” language when insulting people, he assures his geek friends that the rich girls in school aren’t necessarily mean just because they’re wealthy, and he tries to be helpful by pointing out that Johnny should separate his recycling from his trash. In theory, Miguel represents a better and more inclusive future for modern society than Johnny does.

The problem is, Miguel is also getting his ass kicked by high school bullies. That’s because sometimes being the nice guy only gets you so far.

Cobra Kai posits that both sides have a point: Miguel’s woke perspective may better serve society, but there are times when Johnny’s take-no-shit attitude is necessary for survival. A “real man” would find a way to rectify these opposing perspectives and become both a social includer and an honorable defender when the situation calls for it. Cobra Kai asks what it will take for both Johnny and Miguel to find that balance for themselves.

Cobra Kai‘s Central Theme

How a character behaves — both in their passive habits and their active choices — will naturally bring them into conflict with others who behave (and believe) differently.

Viewer interest arises from the tension between two questions: what do the characters want, and what do we want for the characters?

For example, we want Johnny to get his life together, but how he chooses to do so — by restarting the Cobra Kai dojo that directly led to his feelings of inadequacy, shame, and low self-esteem that he’s been dealing with for the past 34 years — is not the healthiest choice. What we really want is for Johnny to regain his confidence and begin living like a responsible adult, but now we realize he needs to learn more lessons before he can put his tortured past behind him and start truly caring about others, and about himself. And, worse, he might make someone else’s life — like Miguel — even worse in the process.

On the other hand, Daniel isn’t exactly living a perfect, stress-free life either. While on the surface he seems to have it all — booming business, local fame, nice house, great marriage, two happy and healthy kids — there are cracks in that foundation. He’s worried that he’s an inadequate father, and his self-esteem is shaken when he sees the Cobra Kai dojo reopen, bringing back painful memories from nearly 40 years ago.

The fear Daniel thought was behind him is back, while Johnny proves it never really left.

One thing that Cobra Kai — and other popular teen dramas from 90210 to Riverdale, and even Game of Thrones — does well is remind viewers that many adults and parents are really just overgrown teens who still haven’t resolved their own childhood traumas.

In the case of Johnny and Daniel, they’re each still dealing with their own feelings of inadequacy, honor, and purpose. Just because Daniel emerged from their high school showdown with a victory doesn’t mean he’s not still filled with self-doubt, no matter how many billboards and commercials he smiles his way through. And just because Johnny was on the losing end of that match, that doesn’t mean he’s a loser — even though he may still feel that way, and even though he may still dream of revenge for taking an L in a formative moment that everyone except he and Daniel have completely forgotten about by now.

The theme of Cobra Kai can be boiled down to: “How do we define ourselves to ourselves?” The actions that these characters take — and the conflicts their actions create — will provide each character with their own answer.

If You Liked This Post, You May Also Like These:

WandaVision’s Biggest Question Gets Deep: Who Are We, Really?

Why Black Sails Has One of the Best Main Characters in TV History

Steve Harrington, Jaime Lannister, and the Secret to Writing a Redemption Arc

1 Comment

Matthew H Lee · December 10, 2020 at 1:31 pm

Phenomenal piece! Tips for my own writing to follow!