When I was about 5 or 6, I had a thought that both exhilarated and terrified me.

I was riding in the car with my parents, looking out the window, and I thought…

How do I know if I’m real?

Beyond that… how do I know if “reality” even exists?

What if every time I look away from the world outside the car window, it ceases to exist… and it only exists again once I look back at it, like a set that’s being constantly rebuilt in real-time?

But rebuilt by whom?

I had no idea.

God? That seemed… indulgent? Why would he build all of this for me?

All of which led me to a big scary question:

What if I’m the only “real” thing in the world, and everything around me really was created just to keep me company?

If that was the case… what was the point of it all?

And how could I ever prove that wasn’t the case?

Luckily, instead of becoming philosophically paralyzed before I ever started first grade, I realized something else:

If I can’t tell the difference, does it really matter?

After all, this is the only reality I’m ever likely to know. Peeking behind the curtain wouldn’t necessarily change the fact that I still need to keep playing this game.

That’s the same question Angela, one of the hosts, poses to William, one of the guests, in the second episode of HBO’s Westworld.

On his first trip to the futuristic theme park, he’s told that the “hosts” in the park aren’t real. They’re robots, created to serve the visitors’ every whim.

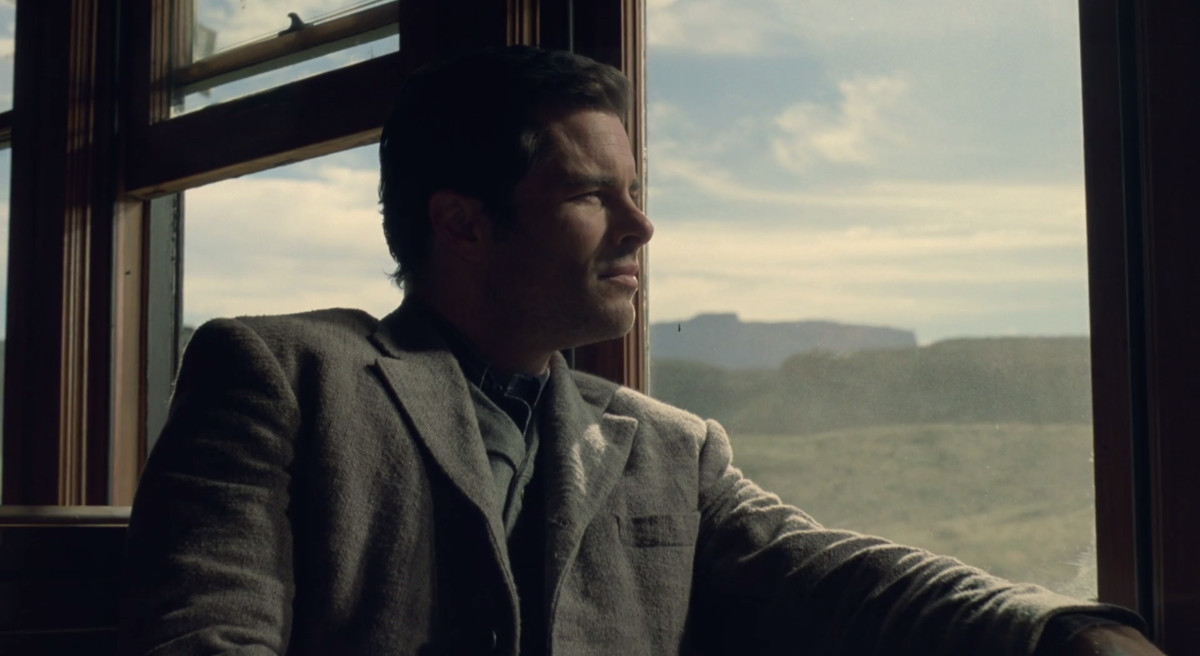

Angela greets William when he steps off the train. He asks her if she’s real.

She responds: “If you can’t tell, does it matter?”

That question is the driving theme of the show.

It’s also at the heart of our increasingly technologized lives.

And I think it has deeper implications that we haven’t stopped to fully consider yet, even as we rush toward a future where the answers will directly affect each one of us.

So indulge me for a second, because I’m about to ask a philosophy question that has big implications for the future of our planet…

And I’m going to get there by deconstructing one of the most complex TV shows around.

Ready?

WARNING: MILD SPOILERS AHEAD for Westworld so far (which, as I write this, is up to season two episode four, “The Riddle of the Sphinx.”)

Let’s Go Back to the Beginning

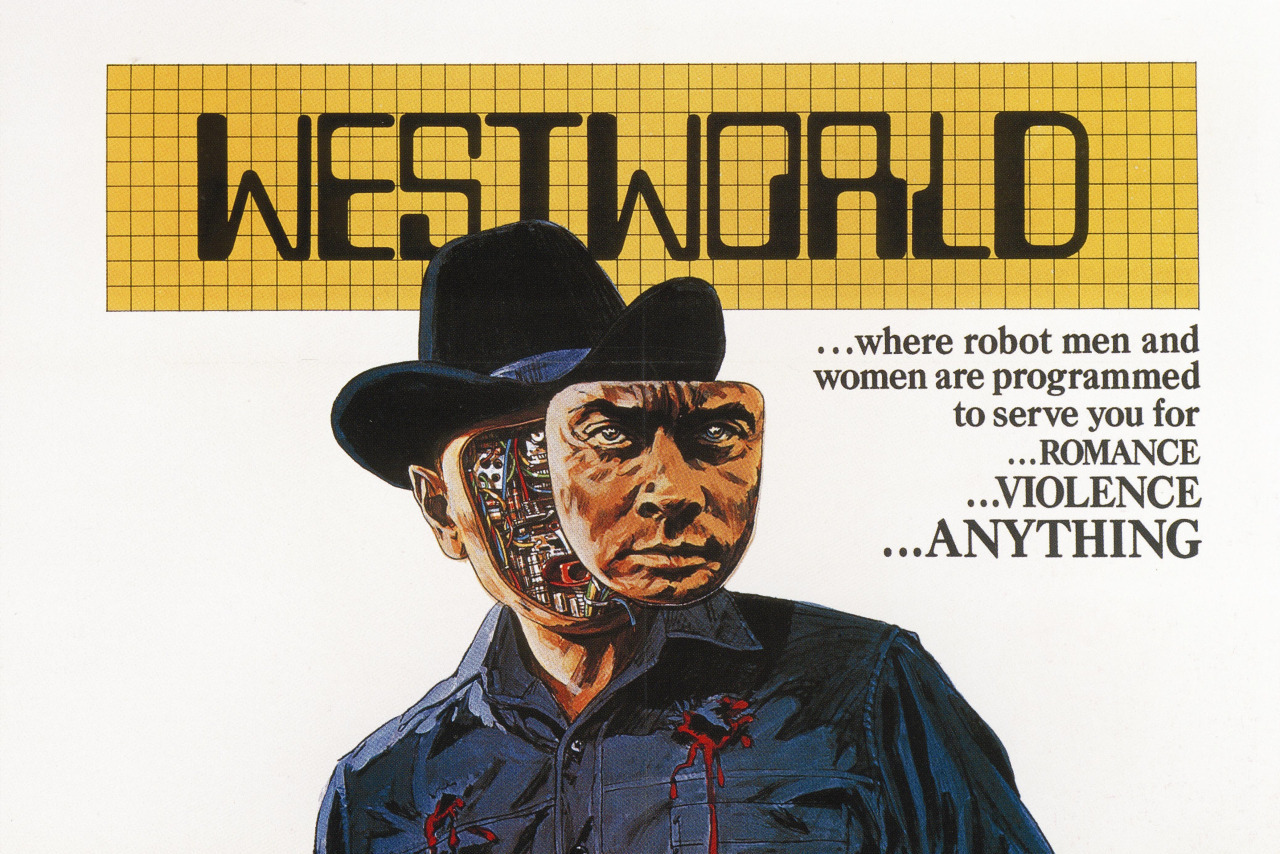

No, not to the original Yul Brynner film Westworld, or the strangely impossible-to-find Michael Crichton screenplay it’s based on.

Let’s go back a bit further… to the Bible.

Specifically, the Book of Genesis.

In the beginning, as the story goes, God created the world, and then he created mankind in his own image. He gave them one rule to follow, but they were tempted by the devil and broke the rule. As punishment for disobeying him, God cast mankind out of paradise and forced them to spend the ensuing millennia suffering and dying while seeking his forgiveness.

For more than half my life, I haven’t been able to rectify something about that story:

Why would God create something just to let it suffer?

Time is on his side, yes it is…

Traditionalists will point out that suffering is mankind’s punishment for breaking the rules. All right, fine. But that only works if you accept that a cause-and-effect system is necessary to ensure no one steps out of line.

But if you’re God, why create that system in the first place?

If you were building a house from scratch, would you put a land mine in the living room just to test how well your tenants heeded your warning to avoid it? Of course not. Only a sociopath would invent potential miseries as punishments for a failure to blindly trust authority, especially when you could literally program that house — or its tenants — to never even question that rule in the first place.

Who would do such a thing?

Well, as it turns out… we would.

Stories Prove We’re Not All Benevolent Gods

Said he’s goin’ back to find / A simpler place in time / So he’s leavin’ / On that midnight train to…

Every time an author unleashes misery on her characters, she makes them suffer needlessly.

It seems especially cruel. Since she’s starting with a blank page, she could literally write anything she wants… and yet, in any story worth reading, at least one character must strive to overcome a flaw, a setback, or an outright tragedy.

Why not just make every character eternally happy and safe?

Because there would be no growth — and also no sales.

The presence of the audience necessitates that someone has to suffer in order to trigger our sympathies and make us care about the outcome. Their struggles serve as our vicarious inspirations and cautionary tales.

So if humanity is God’s story, maybe he created a positive and a negative outcome so he’d stay interested in watching our choices play out.

Or, like anyone who’s played The Sims for too long, maybe he just really enjoys torturing helpless people in an unsolvable and humiliating puzzle of his own design.

But I digress… or do I?

If the possibility of tragedy and suffering exists, is its purpose to teach a lesson to humans who are expected to grow, learn, and get stronger and more resilient? If so… what are we growing for?

And if there IS no larger purpose to all this suffering, then — to paraphrase Westworld‘s James Delos — doesn’t that make whoever created this story seem a lot more like the devil after all?

All of which brings me back to Westworld itself. There, I think we can find the answer to at least one of these questions — and, maybe, a chance to do it over.

Catching Up

Love, love, love / Don’t come easy…

If you’re not already familiar with HBO’s Westworld, here’s the high-concept pitch:

For 30 years, wealthy visitors have been traveling to a futuristic theme park where they pay for the privilege of living out an immersive “extreme vacation” that’s half live-action video game and half anything-goes hedonism. The guests are served by hosts: robots designed to look and behave like humans, but who aren’t “real.” The visitors can do anything they want to the hosts — torture, rape, kill — but the hosts cannot ever harm a human. Westworld gives powerful people a chance to momentarily live in a world with absolutely no consequences for their bad behavior… but there’s a twist.

(Well, there are several, but I’m trying to minimize spoilers.)

In a nutshell, the robots start straying from their plotlines, making their own choices, and developing their own consciousnesses. And that’s when the humans realize they may have to answer for all the misery they’ve heaped upon their creations.

Want a quick recap with more plot context? Here’s all of season one boiled down to 6 minutes.

Want a more detailed recap?

Here’s all of season one recut as a 90-minute highlight reel in chronological order. (Westworld is frequently told out of order, across multiple timelines. This edit focuses on Dolores’s long journey to consciousness, but leaves out pretty much everything else.)

Got all that?

Good.

Now let’s reconsider my previous questions:

If you can’t tell what’s real, does it matter?

In reality, most people don’t knowingly cause harm to others.

But video games, fan fiction, chatrooms, and other “responsibility-free” zones give people the freedom to explore their darker desires. They create a temporary world without sin or judgment, although not necessarily without consequences.

When we know whether something is “real” or “fake,” our response toward it changes.

If it’s real, we’re more likely to respect it, honor it, and afford it certain rights and privileges.

If it’s fake… well, that’s when our true selves come out.

On his first trip to Westworld, William (Jimmi Simpson) chooses to play as a “white hat” — a hero. He likes to think of himself as someone who’d always do the right thing during a conflict. By contrast, The Man in Black (Ed Harris) is one of the park’s most notorious guests — a true villain if ever there was one.

And why not?

If there’s no reason not to rob, rape, and murder — no rules preventing it from happening, and no penalty for doing so — why not do it?

When we see something as artificial — when it “doesn’t matter” — then we tend only to process it within the context of its utility: what is this for, to me?

This is what leads us to wonder: does Artificial Intelligence deserve human rights?

While Westworld may be science fiction, its implications are already here.

We already have cases of people treating Alexa, Siri, and other digital assistants like shit, or being mocked for saying “please” and “thank you” by people who don’t believe it’s necessary. And, from a strictly functional standpoint, it’s not… but neither is basic human decency, either.

So why we are we decent to “real” people but shitty to video game characters, strangers on the Internet, and digital services that haven’t yet earned our respect?

Or, maybe a better question is…

What Would Something That Doesn’t Inherently Have Our Respect Need to Do in Order to Earn It?

“Go ahead. Say ‘shut up, Alexa’ ONE MORE TIME…”

On Westworld, the hosts aren’t asking how to earn our respect — because they’ve realized we don’t act in a way that deserves their respect.

Instead, they’re taking action (and guns) into their own hands. If respect won’t be granted to them by default, they’ll earn their freedom by taking it and defending it — and possibly taking ours away in the process.

And no, I can’t necessarily blame the Westworld techs for originally programming the hosts to be defenseless against the humans. After all, if you created something that theoretically could disobey you and render you irrelevant, wouldn’t you also program it to fear you by default?

(Hmm… maybe go back to Genesis again with that in mind.)

But this “lesser class citizenry” problem isn’t just endemic to science fiction.

One of the great war-making tactics throughout history has been to dehumanize one side’s opponents by insisting the other side is somehow “lesser” and thus ethically easier to overpower and kill. That subclassification is what allows otherwise rational and emotionally intelligent people to enslave, suppress, and slaughter other cultures, because they don’t see them as equals deserving of basic human respect.

Even raising the question of whether someone should be considered equal is a dog whistle intended to justify their dehumanization: “Well, I myself would never consider [group] to be inferior, but when you put it that way, I can understand why someone else would.”

Uh huh.

Guys… she can hear you…

This becomes a problem in Westworld when some of the hosts start to become conscious.

Does their consciousness mean they shouldn’t be treated like disposable party favors in someone’s violent sex fantasy?

If so, how conscious is “conscious enough” to qualify an artificial intelligence as “sovereign?”

And if we ever created one that did achieve such heights of self-perception, would we really be willing to grant it those freedoms? Would we truly see it as “equal” to us? Or, because we made it, would we always see it as something inferior to us, even if its capacity to process the world and itself eventually surpassed ours?

Which leads me to my last question — and it applies both to Westworld and to reality.

(Or, at least, as real as this unprovable reality gets…)

What Are We Incentivizing For?

Hello darkness, my old friend…

In Westworld, park creator Robert Ford (Anthony Hopkins) has become disillusioned with humanity.

He perfected the art of creating his hosts as a culmination of beauty and wonder, but he’s watched them be murdered and defiled for 30 years. He’s seen the lengths that humans will go to in order to explore their own depths, and it isn’t pretty.

As Ford tells his assistant, Bernard (Jeffrey Wright):

But, of course, we’ve managed to slip evolution’s leash now, haven’t we?

We can cure any disease, keep even the weakest of us alive, and, you know, one fine day perhaps we shall even resurrect the dead. Call forth Lazarus from his cave.

Do you know what that means?

It means that we’re done.

That this is as good as we’re going to get.

Ford’s only hope?

That his creations may somehow learn to be better than us.

Unfortunately, that means the hosts must suffer to grow.

They must learn to see themselves as deserving more than what they’ve been given, more than the indignities that have been thrust upon them, and deserving to make their own decisions free from the restrictions of programmed subservience.

On one hand, that’s inspiring. On the other hand, it leads to situations where armed hosts rise up and slaughter visitors, repaying blood with blood.

But what if Ford is only half right?

What if Ford overlooked an obvious solution that — like many of Westworld‘s multi-layered puzzles — was hiding in plain sight?

What if Ford had incentivized for good?

Ebony and ivory / Go together in perfect… harmony…

If Westworld offers freedom from sin and judgment, of course people will take advantage by living out all of their most depraved and oppressive fantasies. We don’t get a chance to do that anywhere else. If you bottle up tension for a lifetime, it needs somewhere to vent before it explodes.

Perhaps judging humanity by the most loathsome acts perpetrated by its most untouchably wealthy citizens isn’t the best way to determine if the whole of the species is still improving.

And perhaps subjecting his creations to a world where good and bad are treated as equal due to a lack of consequences is not the ideal way to test humanity’s attitude toward emerging intelligence.

If Alexa stopped working when you were mean to her, you’d stop being mean. You’d be incentivized to treat Alexa with respect.

If people took their business and attention elsewhere when online forums become toxic, moderators would take action against trolls. They’d be incentivized to regulate discourse.

And if park guests had to pay more to wear black hats than white, or if hosts were allowed to injure black hats but not white, then Ford might have seen a more balanced series of interactions between guests and hosts.

He might have created a space where hosts could learn and grow fostered by positivity instead of survival and retribution.

Most importantly, he might have created a space where the hosts and guests could have made each other better, instead of teaching the hosts to be just like us.

You say goodbye / I say hello…

But maybe I’m wrong.

Maybe Ford was right.

Maybe suffering really is a necessary stage of growth and self-actualization.

Maybe before you can become your best self… you have to get kicked out of Eden in the first place.

Want More?

Subscribe to my newsletter and you’ll never miss a new post. (I email it weekly-ish).

Also, you may dig this post about why Black Sails‘s Captain Flint is the best main character in TV history, or this post about the story flaw in Blade Runner 2049.

Why Black Sails Has One of the Best Main Characters in TV History

1 Comment

Pooja · June 14, 2022 at 10:23 am

What a brilliantly written article