Incredibles 2 is one of the best superhero movies in years.

And as the film’s multi-record-setting box office proves, the public was more than happy to see the Parr family back on the big screen.

But now that Pixar is essentially a sequel factory, and we happen to be living through a summer of “sequels that no one asked for,” Incredibles 2 also has to answer a different question:

Is it really necessary?

That word, necessary, is the heart (or, more accurately, the calculating brain) that powers the theme of the entire Incredibles franchise. And no, I don’t mean the amazingly retro Incredibles theme song composed by Michael Giacchino — although it is a work of art that deserves all of its accolades.

And I also don’t mean the secret universal theme that runs throughout all Pixar movies (yes, including Incredibles 2) and which I revealed in my recap of Coco.

No, I mean the thematic question that influences every choice the characters in the Incredibles cinematic universe have to make, which is:

“How do we decide what is truly necessary?”

The original Incredibles movie already addressed the core thematic questions that have fueled superhero stories for the past 50+ years, like how to balance personal glory with moral sacrifice, and it did so with an impressive mix of eye-popping imagery, family-friendly humor, and heart.

But that was 2004.

Since then, the Marvel Cinematic Universe (which began with Iron Man in 2008) has covered the same topical ground from a rainbow of perspectives.

Thus, to justify a sequel to The Incredibles (and to avoid looking like a calendar-filling cash grab amid the production delays of the seemingly obligatory Toy Story 4), Incredibles 2 would have to tell a story that felt necessary for these times.

Did it succeed?

To answer this, let’s examine the movie’s influences and intentions. Then we’ll compare the ending of the sequel to the ending of the original movie, to see how The Incredibles’ perspective has changed in the 14 years between films.

NOTE: MILD SPOILERS AHEAD for a movie you’ve probably seen and its eerily similar sequel.

Incredible Influences

From Ayn Rand to Brad Bird, Incredibles 2 blends objectivism with idealism to create an imperfect, messy balance where beliefs and actions don’t always coincide — much like the real world.

The Incredibles‘ central family, the Parrs, are an amalgamation of Hanna-Barbera’s “retro-future” family, The Jetsons, mixed with Marvel’s pioneering superhero family, The Fantastic Four.

Beleaguered dad with identity issues? Check.

Mom who not-so-secretly makes all the decisions? Check.

Angsty teenage daughter? Check.

Pure-hearted boyish exuberance? Check.

By mirroring the powers of the Fantastic Four (elasticity, invisibility, super-strength, and — in a slight departure — hot-headed super-speed in place of literally hot-headed fire control), the Incredibles film franchise also essentially doubles as Disney-owned Pixar’s replacement for the film rights to the Fantastic Four, which Marvel famously signed away to Fox before figuring out how to build their own Marvel Cinematic Universe.

(Add in Frozone, whose ice control powers match those of Fox’s other Marvel film rights coup, Iceman from the X-Men, and it’s understandable why Disney-owned Marvel doesn’t feel like overpaying to get those film rights back just yet.)

Visually, Incredibles 2‘s look and feel recalls the wistful comic book art of Bruce Timm (Batman: The Animated Series) and the late Darwyn Cooke, whose odes to Golden Age sensibility feature clean lines, bold action, and falsely rose-colored memories of a simpler time.

Bruce Timm’s kinetic vision of Gotham as an art deco nightmare is echoed by Elastigirl’s action sequences in New Urbrem. There, she must save a hovertrain filled with innocent bystanders from certain death at the hands of the Incredibles 2’s mysterious new villain, the Screenslaver.

Likewise, Darwyn Cooke’s attention to detail even in the midst of a pulse-pounding action set piece underscores the lived-in reality of his most fantastic scenes.

For example, notice the box of tissues cascading through the rear window of a gunman’s flipped car in the Batman and Robin panel below.

This same focus on relatable and mundane details is present throughout Incredibles 2, where the Parrs’ professional and aspirational identities as superhero crimefighters are inseparable from their shared identity as a family that’s struggling with everyday domestic drama.

It’s in that dichotomy that Incredibles 2 — like most superhero stories — finds its defining tension.

And it makes the film’s ending that much more problematic. (I’ll explain why in a second.)

Identity as Purpose

Incredibles 2 director Brad Bird (The Iron Giant, Ratatouille, Tomorrowland) has built his career around the twin themes of individual destiny and idyllic optimism.

Like Cooke’s art, Bird’s films frequently look back at “simpler times” and “better days,” in search of clear delineations between good and evil, black and white, or right and wrong… only to find those distinctions are rarely so clear in retrospect.

In The Iron Giant, a boy’s best friend turns out to be a nuclear war machine.

In Tomorrowland, a utopian society is literally destroyed by pessimism.

And in the Incredibles franchise, people with superhuman abilities must constantly wrestle with the questions of how (and even if) their powers should be used for the greater good, and what “the greater good” actually means.

The dual nature of superheroes as both loyal citizens and extralegal vigilantes has been a cornerstone of the genre since its inception, when Superman, Batman, and The Shadow fought crime while keeping their personal lives secret — ostensibly to protect their loved ones, but also to allow themselves some much-needed privacy.

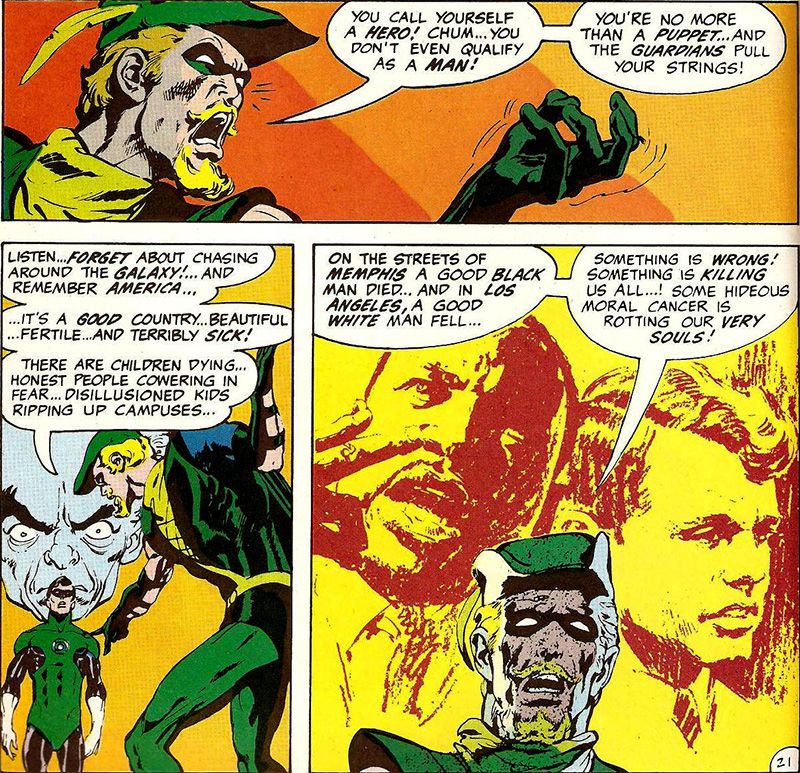

Meanwhile, the legal ramifications of allowing superpowered individuals to act outside the boundaries of the law has been a more recent focus of the genre since the ’70s and ’80s. That’s when Green Lantern / Green Arrow writer-artist Neal Adams first asked what responsibilities a superhero has to fix all the wrongs in the world.

Shortly thereafter, Alan Moore‘s Watchmen raised the issue of humanity’s overdependence on superheroes (and governments) to solve the problems that their very existence inevitably creates for “normal” citizens — a question that was taken to its extreme end in Alex Ross and Mark Waid‘s futuristic cautionary tale, Kingdom Come.

The libertarian ponderings of Moore’s Watchmen (and also of Spider-Man creator Steve Ditko‘s less-famous vigilante, The Question, on whom the Watchmen’s Rorschach was based) fuel this recurring theme in both Incredibles movies:

“How do we decide what is truly necessary?”

To explore how the Incredibles worldview compares to Adams or Moore, let’s examine each film’s plot through the threats posed by their primary villains.

A Hero Is Only As Good as His Villain

In The Incredibles, when superfan Buddy Pine asks Mister Incredible if he can be his sidekick, the hero turns him down.

Offended, Pine (as the villain Syndrome) devotes the rest of his life not only to murdering all superheroes as revenge for what he sees as their hurtful sense of superiority, but he also plans to use his advanced technology to make everyone “super” — because, in his words, “when everyone is super, then no one will be.”

Syndrome traps Mister Incredible by appealing to his ego. Only the intervention of Parr’s super-powered family saves the day.

The lesson? Even heroes need help, and there’s no shame in sacrificing some of your own professional glory to be a family man.

In Incredibles 2, those lessons evolve with the times.

Set literally moments after the ending of the first film, the sequel follows the Parr family as they attempt to navigate the political fallout from the property damage caused by their battle with The Underminer.

Although the Parrs and Frozone save countless lives, many of those lives were actually imperiled by the Parrs’ own actions. Bureaucrats tell them, point blank: “the bank was insured, and we have systems in place to handle this kind of thing.” Bob angrily asks them, “you would rather we had done NOTHING?”

Their answer is unequivocal: “YES!”

(Perhaps in a nod to white-collar corporate criminals everywhere, the Underminer escapes with the bank’s money and is never seen again, nor even pursued. Infer your own lessons here.)

Faced with the soul-crushing possibility of having to get a day job to support his family — a paralyzing fear felt by aspiring artists, entrepreneurs, and other “special” people the whole world over — Bob is saved from this identity-obliterating fate when a technocrat named Winston Deavor (“please, call me Win”) and his designer sister Evelyn offer them a different choice: work for them as paid advocates to help prove that superheroes SHOULD be legalized again.

If this plot sounds a lot like Incredibles 1, when Bob’s day job misery was also cured by a mysterious and lucrative offer to fight an evil robot on behalf of a shadowy employer, that’s because Brad Bird loves those “personal identity fulfilled by moonlighting among untrustworthy techno-billionaires” plot points. (See also: his entire filmography.)

The sequel-mandated twist?

This time, since Bob is too much of an insurance risk (his superpower is basically “mass destruction”), the Deavors choose Elastigirl as their safest bet.

This means Helen gets to be the big hero in public, while Bob must serve as a loyal stay-at-home dad — a “male identity crisis” trope that somehow still generates comedy 35 years after Michael “I’m Batman” Keaton became Mr. Mom.

The Big Villain Differences

Politically-minded viewers love to find libertarian talking points in the Incredibles franchise, like the need for less government regulation and the sovereignty of the individual without regard to the larger needs of society.

But perhaps the most interesting reading of Incredibles 2 is as a grey area between “we’re all in this together” socialism and “every person for themselves” libertarianism.

This is most clearly embodied in the motivational differences between the two films’ villains.

Syndrome doesn’t want anyone to be able to tell him that he isn’t special; he wants to be as revered as the “supers” whose abilities and actions are celebrated by the public. His motivation is ego-driven, because his identity is entirely dependent on how others see him.

Meanwhile, Screenslaver doesn’t want anyone to have to rely on someone else who is more special than they are, but instead to rely solely on themselves. This belief system frames heroes as villains, since Screenslaver believes the very existence of superheroes causes people to abdicate responsibility for their own safety and well-being.

Like Killmonger and Thanos, Screenslaver’s motivation is arguably practical and even justified. But it’s the execution of Screenslaver’s ideals where the argument falls apart. Assigning blame and punishment in childishly black-and-white terms doesn’t acknowledge the larger systemic problems such solutions don’t address.

So while Syndrome and Screenslaver both seek to destroy all superheroes, Syndrome aims to do it conceptually by eliminating the functional need for them to exist, while Screenslaver aims to do it ideologically by eliminating any public desire for them to exist.

The heroes’ solution to defeating each villain is largely the same, and it even follows the same plot points:

- the adults must defy the law in order to learn the truth

- the kids must defy their parents in order to save the adults

- the adults in turn must save the public from certain destruction.

Seems redundant, right?

Well, here’s the real difference:

In the end, each film seems to be saying something slightly contradictory about the nature of heroism, identity, and choice itself.

Key Takeaways from Each Ending

At the end of The Incredibles, superheroes are still illegal, so the Parrs must be heroes in secret.

Bob even tells Dash to limit the use of his powers and let someone else win a track event at school, parodying the generational complaint about celebrating mediocrity in which “every Millennial gets a participation trophy” while the abilities of the truly exceptional are diminished.

But at the end of the sequel, the Parrs and their peers (including a multicolored array of heroes from around the globe) have won the right to use their powers in public.

Now, instead of having to hide their true super-selves in private, they’re free to be themselves in public, amid a world that now appreciates them for their differences. (Cue the various sociological comparisons to identity politics.)

And yet…

This seeming victory actually erases the dramatic tension that fuels the franchise.

At every point until now, and especially in the second film, the Parrs have had to repeatedly ask themselves: “How do we decide what’s truly necessary?”

They were forced to make difficult emotional trade-offs because what they want (the freedom to be themselves and their choice to defend the public) was in conflict with what they needed (to be law-abiding citizens who set good examples while earning legal income that paid for their family’s needs).

Now, without having to choose between family and work, or law-abiding citizenry and vigilante heroism, the Parrs have it all. The removal of this tension effectively turns the Incredibles into…

Well, into the Fantastic Four. Or into any other superhero group who have the freedom to save the day without fear of government reprisal or financial ruin.

The thematic value of the Incredibles franchise was in asking questions about identity vs. purpose that we, as viewers, didn’t have easy answers for.

Is hoping that others will save us a rejection of our own responsibility to save ourselves?

Does having your own powers (or nukes) automatically mean others will want theirs?

What’s more important, family or duty?

What Happens When We Don’t Need Balance?

This is where Randian altruism meets Birdian idealism:

The Incredibles want to defend humanity’s less-powerful citizens from the evil intentions of the world’s villains not just because it’s the morally right thing to do, but because using the special gifts they have to create a positive difference is what makes them feel necessary.

When their powers are outlawed, and when the media and politicians insist that supers are not necessary — or, worse, that their very existence may even be detrimental to society as a whole — it places the Incredibles in a no-win situation:

To be themselves, they would have to break society’s rules and laws… but to follow those rules and laws, they must suppress their true selves.

As Robert McKee says in his screenwriting classic, STORY, a character is defined by their actions during conflict. But that presumes a character has a choice to make.

The Incredibles just removed the characters’ core internal conflict… so what defines them now?

Maybe we’ll have to wait another 14 years to find out.

Want to Read More Posts Like This?

How Avengers: Endgame Succeeds on the Strength of Marvel’s Characters

0 Comments