Aliens turns 35 this week. Released seven years after Ridley Scott‘s original 1979 Alien, writer-director James Cameron‘s sequel was not only one of 1986’s biggest summer blockbusters, but it’s also regarded as one of the best movie sequels of all time.

While the original Alien is essentially a tense slasher-horror film in space, Aliens changes genres. It morphs from a misty suspense thriller into a fast-paced action-survival adventure, all while respecting and expanding upon the legendary sci-fi aesthetics of the original film.

Putting Aliens in Perspective

The success of Aliens (which earned $85 million in 1986, equivalent to $208 million today) is even more impressive when you consider some of its development challenges:

- James Cameron was writing the screenplays for Aliens and Rambo: First Blood Part II at the same time (!) while also directing the original Terminator (!!)

- Sigourney Weaver almost didn’t return to play Ripley because executives at Fox worried that she’d want too much money for the role, but Cameron and producer Gale Ann Hurd refused to make the movie without her

- The role of male lead Corporal Hicks had to be recast just as filming was about to begin when original actor James Remar was fired from the project; he was replaced by Terminator‘s Michael Biehn

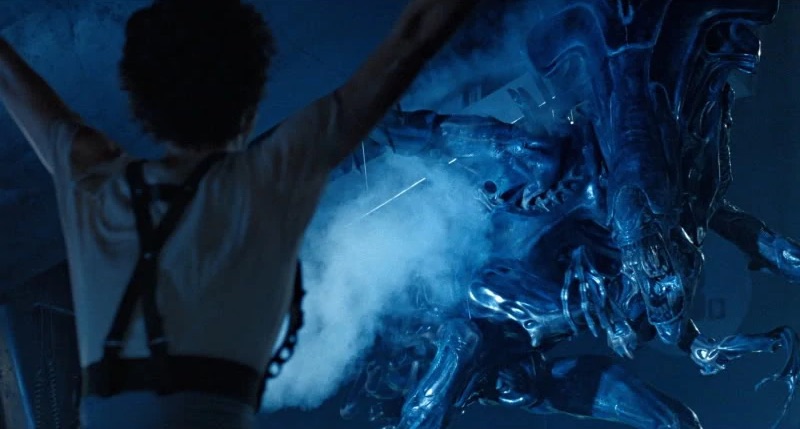

- The film’s Academy Award-winning special effects by Stan Winston — which have influenced generations of sci-fi, action, and horror films — were created on what would today be considered a surprisingly small budget: Aliens had a production budget of between $17 and $18.5 million in 1986, equivalent to $45 million today; by comparison, Pitch Perfect 3 also had a production budget $45 million in 2017, while Avengers: Endgame reportedly cost about $400 million in 2019 (Source: The Numbers)

But the film’s iconic cast, epic effects, and budgetary gymnastics wouldn’t have mattered if it didn’t have such a memorable script.

Let’s study James Cameron’s screenplay for Aliens (you can read it here) to see why it still holds up as one of the best films — and best screenplays — of the ’80s.

RELATED POST: How three-act structure works in screenwriting, and why most films use it

Descriptions That Convey Emotions

Right from the very first page of Cameron’s script, he demonstrates his gift for writing action and description with brisk yet highly emotional language. The screenplay begins with these words:

FADE IN

SOMETIME IN THE FUTURE — SPACE

Silent and endless. The stars shine like the love of God… cold and remote. Against them drifts a tiny chip of technology.

CLOSER: It is the NARCISSUS, a lifeboat of the ill-fated star freighter Nostromo. Without interior or running lights it seems devoid of life. The PING of a RANGING RADAR grows louder, closer. A shadow engulfs the Narcissus. Searchlights flash on, playing over the tiny ship, as a MASSIVE DARK HULL descends toward it.

In just two paragraphs, this sequences does an astonishing amount of crucial writing work:

- It establishes the setting, mood, genre, and scope of the story

- It reconnects us to something recognizable — Ripley’s escape pod at the end of Alien

- It guides the action without using actual camera directions, but instead uses audio and visual cues: a radar sound that gets closer, which signals the arrival of a ship whose motions and size we can clearly visualize

- The phrase “like the love of God… cold and remote” foreshadows that whatever threats arise in this story, our heroes will be on their own

Later, Cameron first describes the surface of the alien planet LV-426, and the human colony that has been established there, like this:

EXT. ALIEN LANDSCAPE — DAY

PANNING SLOWLY ACROSS a storm-blasted vista of tortured rock and bleak twilight onto a metal sign which reads:

HADLEY’S HOPE – POP. 159

Some local has added “have a nice day” with a spray can. Gale-force wind SCREECHES around the corroded sign. In the b.g. is the COLONY, a squat complex surrounded by an angled storm-barrier wall.

EXT. COLONY COMPLEX

SEVERAL ANGLES ESTABLISHING the town, a cluster of bunkerlike buildings huddling in the wind. VISIBLE across two kilometers of barren heath, bg., is the massive ATMOSPHERE PROCESSOR, looking like an oil refinery bred with an active volcano.

Again, we cover a lot of visual ground with minimal words that nonetheless tells us exactly how it feels to live in this place.

Cameron uses this same brisk visual technique throughout much of the script, which essentially operates as a storyboard with words. (It’s worth noting that the shooting script does include a few actual camera directions, but Cameron wrote his original treatment for Aliens without knowing he’d eventually be directing it, so those camera directions may have been added once he knew the movie was his. Nonetheless, his approach to writing description would still have been invaluable to any director.)

Lesson? Don’t just describe what’s happening; direct the viewer’s eye (ideally without using directions).

Compelling Character Introductions

Writing a character introduction, especially for a major character, can be tricky. You want to give the reader (and the actors, and the audience) enough information that they understand who this person is, what they look like, how they move, and how they fit within the ensemble cast and the story’s world. But you also can’t stop the script’s natural pace to drop in a chunk of backstory, or specifically tell the reader how they should feel about this character; you have to let the words lead the reader to their own conclusion.

Here’s how Cameron introduces Carter Burke (Paul Reiser), the man who has just brought Jones the cat into the hospital room of a recovering Ripley.

A MAN crosses the room carrying a familiar large, orange TOMCAT.

RIPLEY

Jones!Ignoring the man she grabs the cat and hugs it to her. Jones seems none the worse for wear and begins to purr.

RIPLEY

Jonesy. You ugly thing.The visitor sits beside the bed and Ripley finally notices him. He is thirtyish and handsome, in a suit that looks executive or legal, the tie loosened with studied casualness. A smile referred to as ‘winning.’

BURKE

Nice room. I’m Burke. Carter Burke. I work for the company, but other than that I’m an okay guy. Glad to see you’re feeling better.Ripley’s gaze turns stony.

RIPLEY

You’re with the company? Then you’re the last person I want to be talking to.

Like the very first scene above, this intro covers a lot of narrative ground all at once:

- Burke doesn’t introduce himself; he waits to be noticed

- His suit is “executive or legal,” which suggests the questions that must be running through Ripley’s and the reader’s minds (who is this guy?), while his tie is loosened with “studied casualness” — and with that phrase, Cameron clues us in that everything Burke does is intentional and serves an ulterior motive; it’s an entire character backstory in just two words

- Note that Cameron doesn’t call it a winning smile, but a smile “described as winning,” which tells us that it’s inauthentic yet serving him well in his upwardly-mobile career

- Burke’s dialogue matches his description: befriend with a compliment, offer a self-deprecating quip that betrays his questionable morality, and conclude with what may or may not be an authentic expression of concern, so that neither Ripley nor the reader is sure she can trust him

- By the end of Burke’s first lines of dialogue, we already have conflict between them

Lesson? Your character’s description, motivation, and narrative purpose can all be conveyed through their outfit and their actions — what they do and don’t do.

Write Like Every Extra Word Costs Money

Later, in the scene where Burke and Lieutenant Gorman (William Hope) visit Ripley to recruit her for their mission to the alien planet, Cameron once again achieves maximum onscreen direction with minimal language. Yet the areas where he does get wordy also happen for a reason.

INT. RIPLEY’S APARTMENT — GATEWAY — DAY

Silence. Ripley, looking haggard, sits at a table in the dining alcove contemplating the smoke rising from her cigarette. The place is minimal, the bed is unmade, there are dishes in the sink. Jones prowls across the counter. The WALLSCREEN is on, a vapid commercial.

The door BUZZES. Ripley jumps like a cat. Jones doesn’t.

INT. CORRIDOR

Carter Burke stands in the narrow, dingy corridor with LIEUTENANT GORMAN, Colonial Marine Corps. Young and severe in his officer’s parade uniform. The door opens slightly.

BURKE

Hi, Ripley, this is Lieutenant Gorman of the…SLAM. Burke buzzes again. Talks to the door…

BURKE

Ripley, we have to talk. They’ve lost contact with the colony on LV-426.The door opens. Ripley considers the ramifications of that. She motions them inside.

These two scenes together are about 3/5 of a page, or around 36 seconds as written, but their pacing is very different. Cameron can afford to spend some extra words describing Ripley’s apartment because this shot directly follows a sequence of horror on the alien planet, so the lengthier description serves as a pacing cue: we’re taking a moment to decompress here before the next plot point arrives.

But once Burke is at the door, the tension picks up, which is matched by the pacing of the writing. Notice all the unnecessary words that Cameron doesn’t include in his script. For example, a clunkier version (with my own 33 unnecessary bold words added) might read:

INT. CORRIDOR

Carter Burke stands expectantly in the narrow, dingy corridor with LIEUTENANT GORMAN, Colonial Marine Corps. Gorman is young and severe in his officer’s parade uniform. Ripley opens the door, but not all the way.

BURKE

Hi, Ripley, this is Lieutenant Gorman of the…Ripley SLAMS the door. Burke buzzes again. No answer. Insistent, Burke talks to the door…

BURKE

Ripley, we have to talk. They’ve lost contact with the colony on LV-426.Ripley opens the door again, all the way this time. She considers the terrible ramifications of what Burke has just told her, and then she motions for them to come inside.

Why does Cameron’s version read better? Economy of language.

Cameron doesn’t need to tell us that Ripley doesn’t answer Burke’s second buzz. He skips right ahead to “talks to the door” and we automatically understand that’s she’s not answering. Similarly, “the door opens slightly” means one thing, and “the door opens” means another; we know what that difference looks like on the screen without needing to add more clarifiers on the page.

Also, in these examples Cameron doesn’t use a single adverb, yet we still have a clear sense of pace and tone.

Lesson? Instead of using adverbs, write with action verbs.

For example, instead of “she runs quickly,” use more evocative terms: “she hurries” or “she speeds” or “she races,” etc. Not only does this save space on the page, but it can also give the actors an emotion to play within the action. And if you do it throughout an entire script, you’ll save several pages of extra space while also keeping the reader’s pace as brisk as the onscreen action.

Multiple Overlapping Obstacles

Aliens would already have been a compelling sequel even if its only innovation was in multiplying the number of alien threats. But that concept by itself wouldn’t have created a story that audiences actually cared about beyond the same typical “who survives the monster” conceit of most horror films.

So in addition to the central, survival-based external conflict of “humans vs. aliens,” Cameron elevates the narrative’s stakes by adding several additional conflicts, each of which affects the others.

First, there’s Ripley’s internal conflict. How will she deal with the trauma of having survived the original alien attack? The fear and survivor’s guilt that she carries with her will need to be faced and overcome in order for her to succeed and survive.

Next, there are Ripley’s interpersonal conflicts. On Burke and Gorman’s mission, Ripley is an outsider in a group of close-knit space marines who don’t initially accept her. She may know more than they do about the threat they face, but if she can’t convince them to listen, they’re all headed for a catastrophe. Meanwhile, as an employee of the Weyland-Yutani Corporation, Burke turns out to embody the worst aspects of corporate bureaucracy, duplicity, and greed; his self-interested choices clash with Ripley’s selfeless ideals to create additional life-or-death obstacles for Ripley and the marines to overcome.

Last, there is a ticking clock — or, technically, three ticking clocks. The first occurs when the transport explodes and the survivors need to barricade themselves inside the colony for seventeen days until another rescue team comes to find them. Cameron then vastly accelerates that timeline when Bishop (Lance Henriksen) discovers that the atmosphere processor is overheating and will likely explode in just a few hours, obliterating everyone. Finally, once an alternate transport is acquired and the processor has begun its countdown to self-destruction, Ripley must go back inside the structure to rescue Newt (Carrie Henn).

Lesson? A good external conflict might initially grab people’s attention, but it’s the internal and interpersonal conflicts that make the story compelling from scene to scene.

The Story’s Theme Connects the Conflicts

What ties all the different conflicts in the Aliens screenplay together? One overarching theme:

Trust and respect.

This theme manifests itself in different ways throughout the script as various characters gain and lose each other’s trust and respect, as well as their own self-respect. For example:

- The commission of suits doesn’t trust Ripley’s report about the original alien attack; they think she may have destroyed the ship herself

- Ripley isn’t sure if she should trust Burke, a representative of the company that sent her to discover the alien in the first place

- The marines don’t initially respect Ripley, Burke, or Gorman because they’re outsiders; they eat at separate tables and generally treat them with suspicion — or, in Gorman’s case, outright derision

- Gorman is “in charge” of the operation, but it’s Sergeant Apone (Al Matthews) that the marines actually listen to and respect

- To prove her mettle to the marines (and herself), Ripley demonstrates that she can be useful by operating a massive heavy loader; this causes Hicks and Apone to begin respecting her

- When things start going wrong, Gorman freezes up and Ripley has to take action in order to save the rest of the soldiers; Gorman even tries to stop her (“That’s an order!”) but Ripley ignores him because he’s proven himself unworthy of respect

- Burke refuses to authorize Ripley’s plan to escape the planet and nuke it from the sky, but Ripley points out that this is a military operation, which means Hicks, as the highest-ranking surviving marine, is technically in charge; Hicks sides with Ripley because he trusts her more than Burke

- When Vasquez (Jenette Goldstein) is injured during an escape from the attacking xenomorphs, Hicks starts to go back for her, but Gorman insists that Hicks go on ahead and he goes back for Vasquez himself; although he’s unsuccessful, his final brave actions manage to earn him Vasquez’s respect

One lack of trust is absolutely crucial to the audience’s expectations: Ripley doesn’t trust Bishop at all. Not after Ash, the android on her last mission, betrayed them. And since Ripley is the point-of-view character that the audience empathizes with, we see every other character through her eyes, which means Bishop seems untrustworthy to us, too. Thus, we’re conflicted: he seems friendly, so we want to trust him, but our past experience (and Ripley’s influence) tells us that’s a bad idea.

Most importantly, Ripley doesn’t respect herself at the beginning of the story because she feels like she failed her daughter. Here’s how Cameron writes the script’s character-defining revelation for Ripley:

Burke ENTERS in his usual mode, casual haste.

BURKE

Sorry… I’ve been running behind all morning.RIPLEY

Have they located my daughter yet?BURKE

Well, I was going to wait until after the inquest…He opens his briefcase, removing a sheet of printer hard copy, including a telestat photo.

RIPLEY

Is she…?BURKE

(scanning)

Amanda Ripley–McClaren. Married name, I guess. Age: Sixty-six… at time of death. Two years ago.

(looks at her)

I’m sorry.Ripley studies the PHOTOGRAPH, stunned. The face of a woman in her mid-sixties. It could be anybody. She tries to reconcile the face with the little girl she once knew.

RIPLEY

Amy.BURKE

(reading)

Cancer. Hmmmm. They still haven’t licked that one. Cremated. Interred Westlake Repository, Little Chute, Wisconsin. No children.Ripley gazes off, into the pseudo-landscape, into the past.

RIPLEY

No children.

(a beat, then)

I promised her I’d be home for her birthday. Her eleventh birthday.BURKE

Some promises you just can’t keep.Let’s get one thing straight… Ripley can be one tough lady. But the terror, the loss, the emptiness are, in this moment, overwhelming. She cries silently. Burke puts a reassuring hand on her arm.

BURKE

The hearing convenes at 0930. You don’t want to be late.

- Here, their differing approaches to emotion helps to crystallize Burke and Ripley’s characters: Burke operates exclusively on the surface while Ripley is experiencing an existential crisis

- The pacing of Burke’s reveals hit Ripley (and us) like a roller coaster of details: Amy exists?! She’s married! She’s 66!! She’s dead?!? And while Ripley is dealing with this gut punch, Burke meanders through the minor details until he drops the final bomb: no children. Ripley may have survived, but now she’s all alone, with no family.

- Burke’s advice — “Some promises you just can’t keep” — might seem like words of comfort, but they also reveal how he feels about trust, foreshadowing his own inability to live up to it

Ripley will spend the rest of this story trying to make up for her broken promise. And Cameron gives her the perfect chance — and the perfect complication — in Newt, the little girl that Ripley and the marines rescue in the colony.

Lesson? Overlapping plots can be tied together by an overarching theme, whose exploration can help magnify conflicts and guide character choices.

Your Main Character Is Responsible for the Ending of Your Story

As the main character, every important thing that happens in this story depends on Ripley. From a story structure standpoint, another way to think about this is: the ending of this story would not be possible if Ripley wasn’t in it.

Without Ripley, the marines would have discharged their guns when the aliens first revealed themselves, which would have caused a thermonuclear explosion beneath the atmosphere processor that would have blown up the entire colony, including Newt, Hicks, and Bishop. Those three only survive because of Ripley.

Even if the marines had somehow escaped from the alien hive and barricaded themselves in the colony, Newt is the one who leads the survivors to safety thanks to her knowledge of the air ducts… and the only person who was able to get Newt to talk was Ripley. Once again, without Ripley, everyone dies.

Likewise, even if someone else had gotten through to Newt and formed a bond, and that connection helped them escape in the nick of time, they still may not have known how to use the mechanical loader that Ripley operates to defeat the Alien Queen in the script’s final moments.

And yes, even if someone else did kill the Alien Queen and the remaining survivors were able to return to Earth, Burke probably would have sabotaged the other marines’ cryogenic pods on their way home in order to smuggle a facehugger back to Earth, where it would likely run rampant and cause a mass extinction event. The only reason this doesn’t happen is because Ripley figures his plan out first.

But her actions are just the first half of Ripley’s character arc; they’re what she does, but not why she does them. They’re plot points that have to make sense within the logic of the story, but to really resonate, they also have to be anchored in character development.

The other half of Ripley’s character arc depends on Newt.

How so?

- Newt hides from the marines, but Ripley is the one who gets her to come out of her hiding place

- Gorman can’t get Newt to talk so he gives up on her (“we’re wasting our time”), but Ripley is patient with Newt and treats her with care and respect, which helps Newt slowly begin to open up

- Thanks to this bond, Newt starts sharing what she knows with the survivors; her experience and knowledge of the colony will end up saving some of their lives

- After protecting Newt several times, Ripley loses her when Newt literally slips through her fingers and falls down a pipe; she and Hicks attempt to rescue Newt but they’re forced to retreat when a xenomorph nearly kills them both and badly injures Hicks

- With just minutes to go before the whole place explodes, Ripley uses all the weapons knowledge she learned from Hicks to re-enter the facility, find and rescue Newt, and lay waste to the alien hive

- Ripley’s final showdown with the Alien Queen isn’t just a one-on-one battle against the story’s antagonist; it’s a battle for Newt, because the Queen is about to kill Newt when Ripley initiates the final showdown (“Get away from her, you bitch!”)

By finding, bonding with, protecting, and ultimately rescuing Newt from the aliens, Ripley manages to quiet her own inner demons of failure as a mother. She can’t bring her daughter back or undo what’s in the past, but she can start a new life with a little girl who only survives life-threatening terror because of the brave choices that Ripley makes.

Lesson? Go back through your own screenplay and ask yourself two questions:

- “If my main character wasn’t in this story, would it still end this way?” If the answer is yes, revise until the ending is only possible because of the main character’s actions

- “Do the choices my main character makes resolve both her inner conflict and the theme?” If not, keep revising until they do.

The Ripley–Hicks Connection

Not every story needs a romance, but they all need a human connection.

In Aliens, Hicks becomes the male lead by necessity when his two superiors, Apone and Gorman, are removed from the story halfway through the script. This puts Hicks in charge at the tactical level, but he recognizes that Ripley understands these creatures better than he does, so he shares his leadership status with her.

While there could be romantic possibilities between the two of them, they can barely acknowledge this fact because they’re preoccupied with trying to stay alive during an alien attack. So instead of flirtation, their growing bond is based on mutual respect: Ripley respects Hicks’s calm demeanor under pressure, his natural leadership, and his willingness to look out for her while also teaching her how to fend for herself; Hicks respects Ripley’s bravery for even coming on this mission in the first place once he realizes what the stakes really are, as well as her patient and nurturing care toward Newt.

How does Cameron build this connection on the page? Through small details. For example:

- During their drop to the planet’s surface, Hudson (Bill Paxton) is bragging about how much firepower they have, but Hicks tells him to can it because he can tell it’s making Ripley uncomfortable. (However, this line is actually given to Apone in the film, not Hicks, because it makes sense that Apone would reprimand Hudson since he’s the commanding officer; instead, Hicks is shown sleeping during the drop, to reinforce how calm he is under pressure.)

- When Ripley decides to stay outside the colony alone in the armored personnel carrier, Hicks tells Frost to keep an eye on her.

- When they first find Newt, the girl is hiding, scared, but Hicks suggests Ripley approach her rather than one of the marines. Ripley steps forward, “trusting his judgment.”

- When Ripley points out that Hicks is in charge, not Burke, Hicks responds by ordering Ripley’s suggested alien-nuking strategy verbatim, confirming that he fully trusts her judgment, too.

Interestingly, the scene that cements their bond also differs between the script and the finished film. In the screenplay:

Hicks sets down his welder and removes what looks like a wristwatch from his arm. It is a standard issue LOCATING BEEPER.

HICKS

Here, put this on. Then I can find you anywhere in the complex on this —He indicates a tiny LOCATOR hooked to his battle harness. He shrugs, a little self-consciously.

HICKS

Just a… precaution. You know.Ripley pauses for a moment, regarding him quizzically.

RIPLEY

Thanks.HICKS

So, uh, what’s next?She consults a printout of the floor plan.

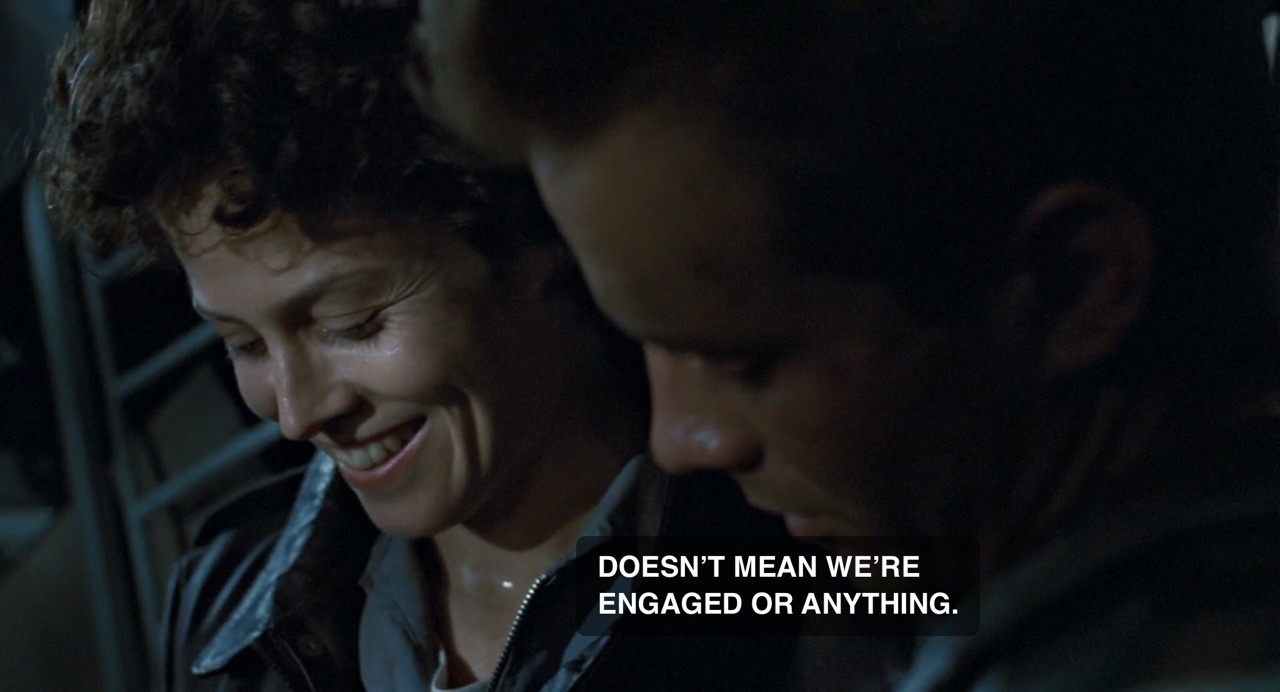

That version of the scene suggests Hicks is more shy than the self-assured version of the character that Biehn was playing, which might explain why the finished film adds an extra line:

HICKS

It’s just a precaution.RIPLEY

Thanks.HICKS

Doesn’t mean we’re engaged or anything.

His nonchalance lets both characters laugh at the mild absurdity of the situation without losing their focus, their mutual respect, or the possibility of something happening between them in the future… if they survive.

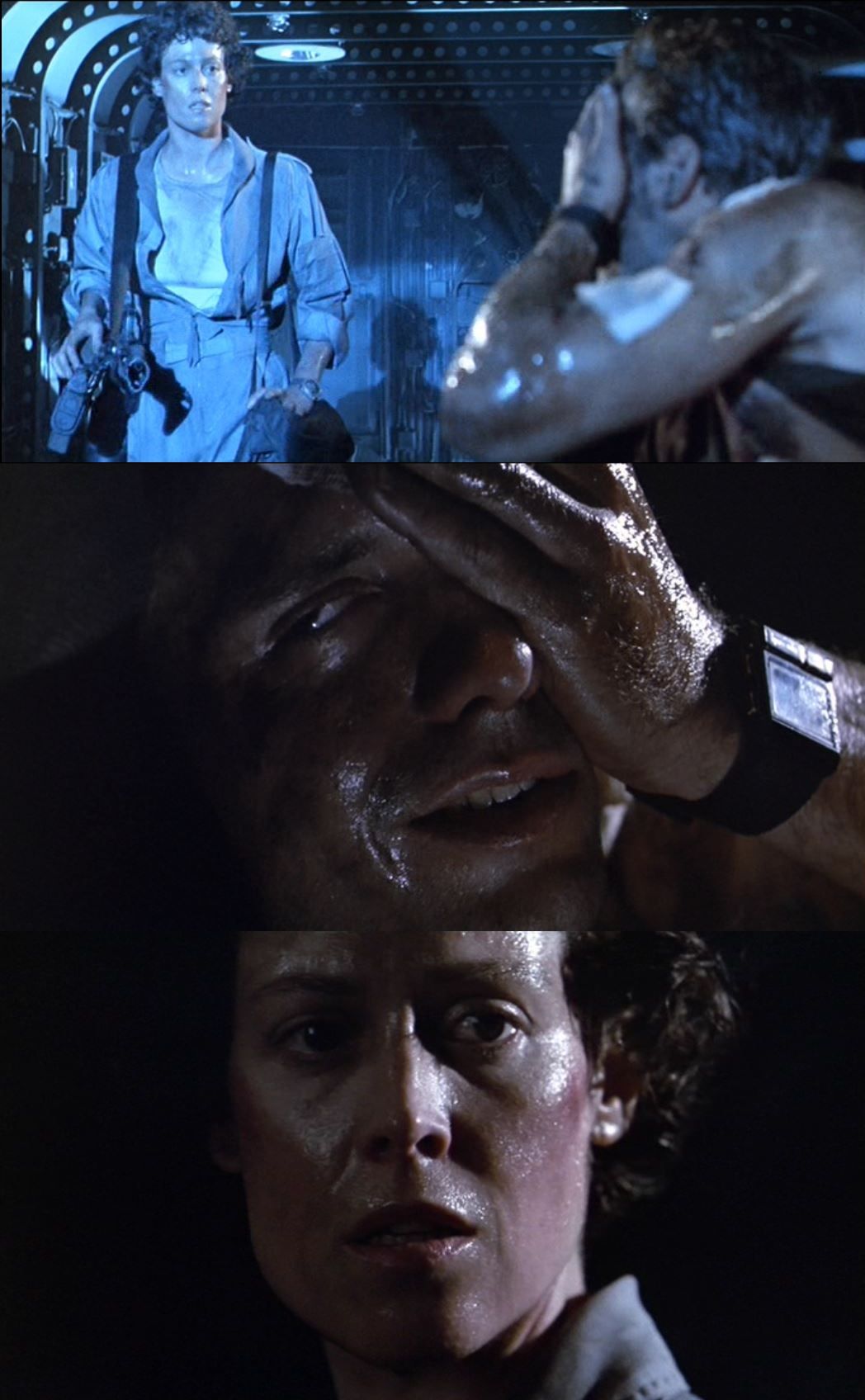

This bond pays off at the climax, when Ripley is about to leave the injured Hicks on the escape transport and go rescue Newt.

RIPLEY

See you, Hicks.Hicks is holding a wad of gauze plastered over his face.

HICKS

Dwayne. It’s Dwayne.Ripley grabs his hand. They share a moment, albeit brief. Mutual respect in the valley of death.

RIPLEY

Ellen.HICKS

(nods with satisfaction)

Don’t be long, Ellen.

This scene also plays differently in the film, as Ripley doesn’t take Hicks’s hand during this sequence. Instead, they’re standing several feet apart, each in their own closeup.

Again, this is likely due to the onscreen chemistry between Weaver and Biehn, which has been so well established by this point in the film that they can convey their emotions without needing to make it obvious through physical contact. This makes their connection feel more mature and believable, while the purpose of the scene remains the same: since they may never see each other again, Hicks wants them to remember each other as people, not just as names.

Lesson? You don’t always need a full-fledged romantic subplot in your script — especially if it would be preposterous to have one during its circumstances — but there are plenty of other kinds of relationships that can give characters a chance to connect and grow.

Every Upside Has a Downside

In the original Alien, the xenomorph was stalking a small ship of general contractors. Ripley and her colleagues didn’t have tons of firepower to protect themselves then, so you might think that having an entire squad of space marines would improve the odds of surviving against the aliens.

But you’d be wrong.

That’s because Cameron does a masterful job of making sure every seeming advantage the humans have actually works against them, and that everything that seems designed to protect them ends up nearly killing them.

Some examples:

- Sure, the marines have flamethrowers… but when the xenomorphs first attack, the marines are so surprised that they accidentally set each other on fire with the flamethrowers instead

- Sure, they have an armored personnel carrier… but when Ripley pushes Gorman aside and drives it into the hive to rescue the marines, her panicked escape grinds the gears so badly that they won’t be able to use it again without repairing it

- Sure, they have an air transport that can evacuate them back to their ship… but when a xenomorph kills the pilot while it’s in mid-air, the resulting crash not only destroys their way off the planet, but it also collides with and wrecks the personnel carrier, causing most of their firepower to explode

- Sure, Ripley can fight the Alien Queen with the power loader… but when they fall on top of each other in close quarters, the weapon can just as easily become a tomb

Lesson? The bigger the advantage your characters seem to have, the more trouble it should actually cause when things go wrong.

Hide the Setups for Your Payoffs in Plain Sight

The whole reason I wanted to write this post in the first place is because Aliens is a perfect example of how to write effective setups and payoffs. Nearly every character quirk leads to a catharsis, surprising choices organically stem from previously established motivations, and what may seem like minor details or exposition in dialogue often turn out to be clues to future twists — yet almost all of the setups are hidden by flashier information.

For example, when Ripley wants to know what’s laying all the eggs, Bishop suggests it’s something they haven’t seen yet; Hudson then suggests the aliens might operate like ants or bees, with a huge queen (“Yeah, the momma. And she’s badass, man. Big.”) But this conjecture is immediately followed by a more serious revelation: Bishop tells Ripley that Burke has ordered him to keep the facehugger specimens alive to bring to Earth, which overtakes both Ripley’s and the audience’s attention. Thus, Burke’s revelation as a heel buries Hudson’s musing about a possible queen, but that seed is still planted. (It also helps that Hudson has proven himself to be mostly full of tall tales, so the audience is inclined to disregard his latest observation as more nitwit blabbering.)

In the next secene, when Ripley confronts Burke about his scheme to bring the facehuggers home so they can be used as military weapons, she tells him she’s going to bring him up on charges as soon as they get home. This is a choice that’s true to her character as someone who insists on always doing the right thing, yet it has consequences: later, when the facehuggers attack Ripley and Newt, Burke intentionally ignores her calls for help. But when Ripley initially calls Burke out, we don’t have time to think about the possibility that Burke is a potentially serious threat because that scene is immediately followed by an alarm as Hicks announces that aliens are in the tunnels leading to the colony. Once again, something we probably should spend more time thinking about is pushed to the background by the arrival of a more immediate danger, but that future narrative seed is still planted.

Even Hudson’s famed breakdown (“Game over, man!” — which was actually ad-libbed by Paxton) is a payoff to an earlier setup of character quirks. Hudson is introduced as the embodiment of jokey machismo, but his over-the-top bravado is quickly shown to be a front; when Drake (Mark Rolston) grabs Hudson so Bishop can perform his famous “knife trick” on him, Hudson is terrified.

Later, despite his “ultimate badass” speech to Ripley — which actually doubles as an inventory rundown so the audience understands all the weaponry the marines have at their disposal — Hudson is the first to lose his nerve when the aliens attack, and Ripley is the one who has to get him to snap out of it.

Lesson? Audiences are smart, and a lifetime of watching movies and TV has trained them to look for obvious setups and payoffs. To help disguise the surprise of a payoff, don’t linger on the setups; instead, redirect the audience’s attention to something more immediate.

Earned Catharsis, Destroyed

Like any good monster movie, Aliens essentially has two endings.

First, Ripley saves Newt, only to discover that Bishop has indeed flown away without them. Her suspicions were right all along! She was right not to trust him!!

But just as the Alien Queen approaches, Bishop returns to rescue them after all!!! They get away safely, proving that Ripley’s distrust of Bishop was misplaced. He is trustworthy, and he does deserve her respect (and ours).

Ripley acknowledges this when she finally compliments him (“You did okay, Bishop”), and Bishop takes a moment to appreciate the fact that he’s finally proven himself — just as the Alien Queen destroys him in a sneak attack!!!!

The ensuing sequence, where Ripley uses the power loader to fight the Queen — the same loader that she’d used to prove her own worth to Hicks and Apone when their mission began, and to regain her own sense of self-respect as a capable contributor to their cause — completes Ripley’s arc and concludes the plot. And, in a twist, Bishop even “survives” in pieces, so that his subplot doesn’t end on a tragic note.

The moment when the Alien Queen stabs Bishop through the chest is one of the most memorable jump scares in film history. It achieves this distinction not just because of how it happens, but when it happens — mid-celebration, just as we thought two characters whose interpersonal conflict has been resolved were about to celebrate a very well-earned catharsis.

Lesson? Your emotional payoffs must be earned, and so do your surprises. Sure, a passing moment of camaraderie or a cheap jump scare can provide your audience with some clichéd emotional cues. But anchoring those moments within a character’s established conflicts, arcs, and themes will lead to an even more memorable and effective emotional arc for your entire story.

If You Liked This Post, You May Also Like…

How Avengers: Endgame Fulfills the Emotional Arcs of Marvel’s Characters

0 Comments