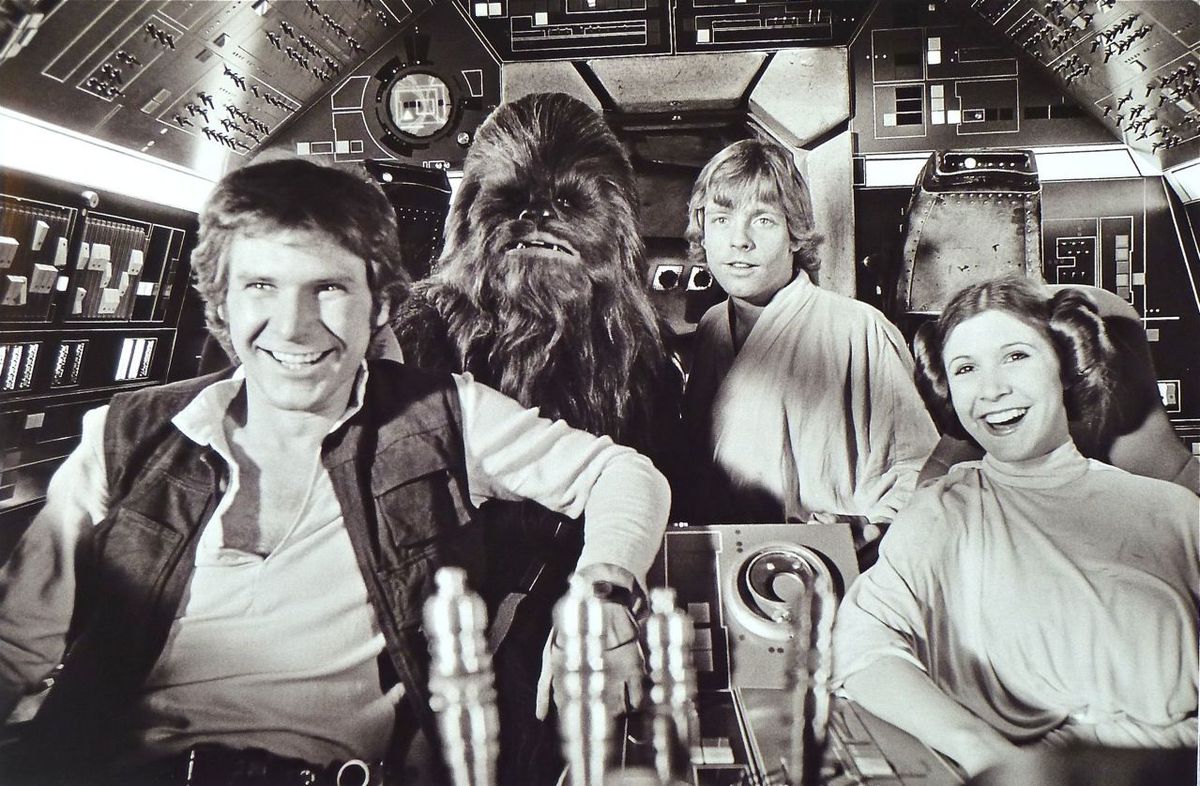

It’s a well-known secret that the original cut of Star Wars would likely have failed at the box office if its editors (including George’s then-wife, Marcia Lucas) hadn’t saved the movie.

But did you know just how important their changes were to the film’s blockbuster success?

As it turns out, the culture-changing impact of George Lucas’s vision for Star Wars owes as much to his editing team’s insights (and the blunt advice of Lucas’s film school buddies Steven Spielberg and Brian De Palma) as it does to the creative genius of sound designer Ben Burtt, composer John Williams, and Lucas himself.

Here’s a great video that itemizes over a dozen of the changes made to Star Wars between its legendarily bad rough cut and the iconic version that was eventually released into theaters in May 1977.

One of the key points the video makes is the crucial importance of pacing.

The success of any story ultimately depends on its audience’s ability to do three things:

- Follow the story’s logic

- Form an emotional bond with the characters

- Prefer a specific outcome from among the known possibilities

This means an editor’s primary job isn’t to ensure that the film makes sense, or that the cuts match and there aren’t any mistakes or discrepancies. No, an editor’s most important job is to organize information for the audience to maximize the story’s logical flow and emotional impact.

Unfortunately, as even George Lucas knows, it’s easy to get this part wrong.

How?

Three easy mistakes:

Don’t give an audience too much information too quickly, or you’ll overload them and they won’t know what to pay attention to.

Don’t mishandle the crosscutting between storylines, or you risk losing the emotional thread that leads from setup to payoff.

And don’t introduce a key element without giving it sufficient attention, or your audience could miss what matters about a clue, character, or plot point — and that means the eventual payoff won’t have the logical and emotional impact you’re counting on.

Wait… you’re telling us this is all because of midichlorians?

Star Wars offers a fantastic example of the power of good film editing, because having the rough cut available means that we can see the before-and-after results of the choices the editors made.

But even when we can’t literally see the other possibilities, we can easily imagine them… and they’re not always pretty.

Here are three more examples of how the organization of information in a movie affects the audience’s expectations and their emotional investment in the payoff.

Casablanca and the Well-Timed Reveal

Two very attractive hills of beans

In one of the greatest ticking clock thrillers of all-time, we don’t learn about Rick’s past life with Ilsa until after their paths have crossed for the second time. Withholding this backstory, which contains the seeds of Rick’s controlling motivation, is crucial to the plot’s effectiveness.

If Casablanca had opened chronologically, we’d have begun with Rick and Ilsa in Paris, and her abandoning him at the train station would have signaled the end of Act One.

Instead, we open the film with intrigue, murder, dark humor, and political gamesmanship… and only then, after the tone and setting have been established and we think we know what the stakes are, do we then realize just how complicated Rick’s week is about to get.

The lesson?

Revealing the underlying reason for a character’s motivation after establishing the known stakes can make for a much more powerful and humanizing twist than simply spoon-feeding the audience the information in order.

On the other hand, there are times when following chronological order is exactly what you need to set the audience’s expectations.

The Butterfly Effect

Guess who’s coming to dinner?

You know what’s fun?

Thrill rides.

You know what’s not fun?

An hour of exposition before the thrills kick in.

And yet, 25 years ago, Steven Spielberg bet that audiences won’t hate exposition if they don’t realize it’s happening… and they proved him right to the tune of $350 million dollars.

Spielberg is a master of setup and payoff, as his films from Jaws and E.T. to Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan have proven. But what he doesn’t get enough credit for is how simply and effectively his films convey huge amounts of information that the audience needs in order to understand the plot, bond with the characters, and desire a possible outcome.

Take Jurassic Park.

When Spielberg and screenwriter David Koepp adapted the bestselling Michael Crichton novel, sure, they had a magnetic premise — an amusement park filled with actual living dinosaurs goes terribly wrong! — but think about everything the audience needs to know before we get to the part where the dinosaurs actually run amok.

First, we have to…

- Establish the tone (yay science! uh-oh doom!)

- Introduce ten main characters, their personalities, and their desires

- Establish the geography of the island

- Indulge in a majestic spectacle [that also establishes the size of the dinosaurs]

- Explain the plot-critical science at work (DNA, amber, chromosomes, carnivores)

- Clarify the safety mechanisms and how they [should] work

- Lampshade the fact that Nedry is about to break the system for personal gain

Only then do we reach the point where we have all the information we need to:

- Form clear opinions about each character

- Understand the scope and layout of the island

- Appreciate the comparative size and strength of the dinosaurs

- Formulate expectations based on known motives, threats, and genre tropes

- Know what’s at stake [and just how screwed everyone is about to be]

Wisely, Koepp and Spielberg hide most of their exposition within amusing dialogue, conflicts between characters, and even an animated video that sugarcoats the obligatory science lesson.

But couldn’t Spielberg have just… skipped some of these steps?

For example, what if Nedry had scrambled the computers just after the visitors arrived at the island?

Sure, that would save us several scenes of dialogue, exposition, and world-building, and allow us to jump straight into the whole reason we came to see the film in the first place: to watch humans try to escape from massive hungry dinosaurs on the loose.

But…

If that kind of high-stakes conflict had happened in the film’s first twenty minutes, we wouldn’t yet have the information we need to clearly understand the stakes. We wouldn’t know where the characters might escape to, how steep their odds are, or why we should care about them as anything more than victims in a slasher film.

Instead, by giving us nearly an hour of setup, Spielberg gives us everything we need to process the fast-paced action once the T-Rex breaks free and our worst fears kick in — made all the worse because now we clearly understand just how bad things may get.

The lesson?

If your story requires your audience to process a huge amount of information in order to accurately appreciate the stakes, pace your exposition alongside rising tensions.

Lastly, there are some cases where less really is more.

One Is the Loneliest Number

To this day, I still feel bad for this horse

Sometimes, tunnel vision is a good thing.

While this lesson applies broadly to most suspense and horror films, it works on TV, too.

In the pilot episode of The Walking Dead, we only know as much about the sudden and mysterious zombie plague as Rick Grimes himself does. As a result, we share his sense of inescapable dread, which is the POV that the entire series is built on.

With Rick as our only window into this new world for much of the first episode’s screen time, showrunner Frank Darabont can take his time steeping us in isolation and paranoia. This slow burn means every encounter with a zombie serves two purposes:

- It gives Rick (and us) another clue about the scope of the outbreak

- It releases our buildup of tension with a momentary burst of life-or-death action

All of which leads to the episode’s final twist: just when it looks like Rick’s about to be overrun by a horde of the undead, he learns he’s not alone after all — and that moment opens up his (and our) world, setting the entire rest of the series in motion.

The lesson?

If you want to make sure your audience is only focused on one emotion — like fear — don’t distract them with details (like a plot) until it’s absolutely necessary.

As for Marcia Lucas…

You definitely want to bookmark this in-depth look at the career of Marcia Lucas. Her impact on pop culture is almost as interesting as the odd twists in her personal life with George.

Enjoyed This Post?

… then you may also like why Solo keeps the spirit of Star Wars alive.

2 Comments

How Hollywood Can Inspire Your Courtroom Presentations | IMS Consulting & Expert Services – Movie News Live · December 19, 2022 at 4:35 pm

[…] or star actor, even if they are significantly less celebrated. In fact, the story goes that the original Star Wars was “saved” (or at least vastly improved) by those who edited […]

How Hollywood Can Inspire Your Courtroom Presentations - Litigation Insights · August 21, 2020 at 11:05 am

[…] or star actor (even if they’re significantly less celebrated). In fact, the story goes that the original Star Wars was “saved,” or at least significantly aided, by those who edited […]