We often use the word “hero” to describe the main character of a story. But since the 19th Century, our most popular stories usually aren’t about heroes.

Instead, they’re about anti-heroes.

So what’s the difference, and why are traditional “heroes” getting so hard to find?

To understand this, we first need to answer a surprisingly complicated question:

What Makes a Hero?

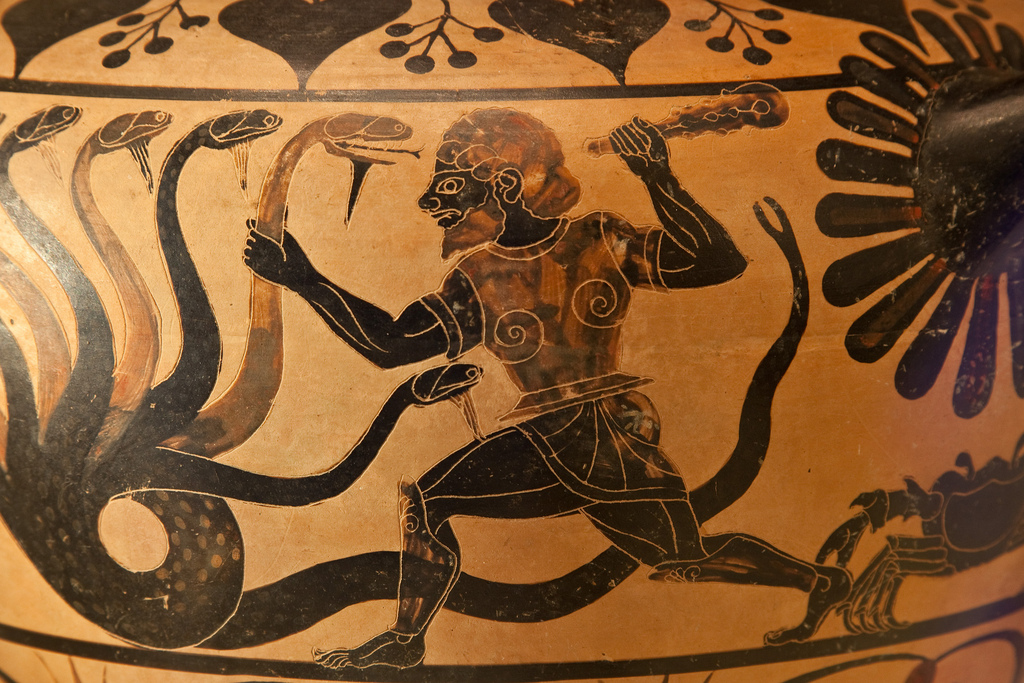

The original super-hero

The word “hero” derives from the Greek term for “defender” or “protector.”

The ancient Greeks told epic stories of legendary heroes like Achilles, Odysseus, and Heracles (or, in Roman, Hercules). These heroes usually shared three traits:

- They were the mortal descendants of gods

- They were exceptional above all other men regarding some particular skill

- As mortals, they were destined to die

Thus, both bravery and tragedy are interwoven in the source code for a hero: their exceptionalism makes them capable of incredible feats, but their mortality means they can’t live forever, so every fantastic risk they take could be their last. Their vulnerability makes every risk they do take feel more dramatic, rather than seeming like an easy and inevitable win.

(That’s why even gods like Thor end up feeling surprisingly relatable.)

Centuries later, we’ve departed from the idea that heroes are children of gods, but their exceptionalism remains.

I could be your hero, baby…

We rarely tell stories about “normal” people. Instead, we tell stories about people who may appear to be normal, but whose exceptional abilities enable them to achieve feats that normal people never could. (Think of Sherlock Holmes, Harry Potter, or Katniss Everdeen.)

We also tell stories about super-heroes, a 20th Century update to Greek myths in which men and women are granted godlike powers through science, magic, or mutation, rather than through divine interventon.

But even our super-heroes are not all “heroes” in the traditional sense.

That’s because a classic hero also requires a clear code: to boldly stand FOR something, which requires clearly and simultaneously standing AGAINST its opposite.

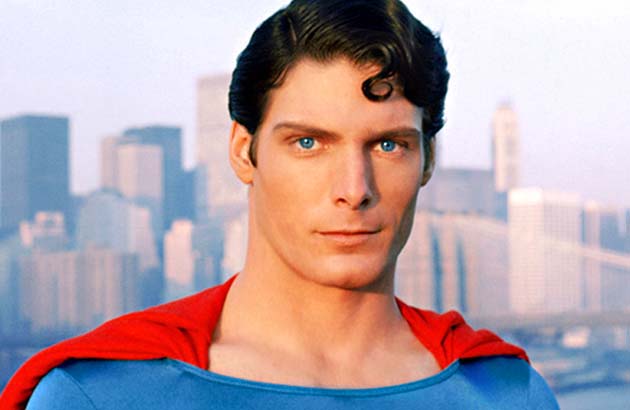

Actually, neither a bird nor a plane…

Superman, Wonder Woman, and Captain America are designed to be classic heroes. They stand for truth, justice, and the idealized equality of the American dream. This means that, by definition, they also stand against dishonesty, corruption, and the abuse of power.

Heroes also possess one more defining quality that separates them from anti-heroes, which we’ll get to in a second.

But first…

What Makes a Character an Anti-Hero?

Is Batman a hero, or an anti-hero?

What about James Bond?

Or Arya Stark on Game of Thrones?

In each case, those characters behave more like anti-heroes than heroes.

What’s the difference?

Generally speaking, an anti-hero is a compromised hero.

Instead of clearly and unequivocally standing FOR something, an anti-hero stands for AN END regardless of the MEANS used to achieve it. Their ends are often the same as a hero’s values — truth, justice, equality, etc. — but the means they use to achieve and defend those ends make it impossible for them to entirely stand against something.

Dancing with the devil in the pale moonlight

For example, Batman is a vigilante. He believes in justice, but his methods for defeating crime lead him to work outside the law.

James Bond is a secret agent with a license to kill. He believes in protecting the world (and especially his home nation of the United Kingdom) from evil, but he’s empowered to break the law, spy, steal, murder, and casually commit war crimes, all under cover of being the good guy.

And Arya Stark seeks justice and equality in a world filled with corruption and brutality… which leads her to adopt those same methods in order to “win” a game that corrupts all players.

But it’s not just the laws or rules of society that anti-heroes frequently find themselves working around. It’s also their own moral compasses. That’s because anti-heroes are frequently torn between upholding their own ideals and doing what’s personally convenient.

Scruffy-looking nerf herder and friends

In Star Wars, Luke Skywalker is the hero. He may initially be reluctant, but his core beliefs in justice, honor, and defending the world from evil compel him to take ever-bigger risks as he faces off against his mortal nemesis, Darth Vader.

Meanwhile, Han Solo is the anti-hero. He professes to not care about anything other than money and his own well-being, which gives him an excuse to ignore the risks he’d rather not take. And yet, one of the film’s most cathartic moments is seeing Han and Chewbacca swoop in to save Luke from certain death so Luke can complete his mission to blow up the Death Star.

Did Han have to make that choice? No. He’d already absolved himself of the need to take action by articulating his own code — to paraphrase Rick Blaine in Casablanca (and countless film noir private eyes), “I stick my neck out for no one.”

That’s what makes it so emotionally satisfying when Han decides to take that final risk after all: his eventual embrace of a higher moral code makes him a compelling anti-hero. (See also: Captain Jack Sparrow in the first Pirates of the Caribbean movie.)

But there’s one more ingredient that determines whether a character is a hero or an anti-hero, and it has nothing to do with superhuman abilities or moral grey areas.

In fact, even more than our growing distrust of governments, justice departments, and economic systems — all of which are usually the territory that we expect “heroes” to defend and protect — I believe it’s this missing ingredient that has led to the meteoric rise of the anti-hero since the 1960s.

So, what is that missing ingredient?

Sincerity.

The Rise of the Anti-Hero in Pop Culture

A man’s gotta have a code…

The rise of the anti-hero mirrors the rise of postmodernism in America.

When you believe in clear ideals, it’s easy to have heroes. But when you start to deconstruct society, government, and media, seeing anything other than a grey area becomes increasingly difficult to the point that having unshakable beliefs seems childish and corny.

In other words: to be a modern “hero” means embracing ambiguity and rejecting sincerity…

… which means all modern heroes are really anti-heroes.

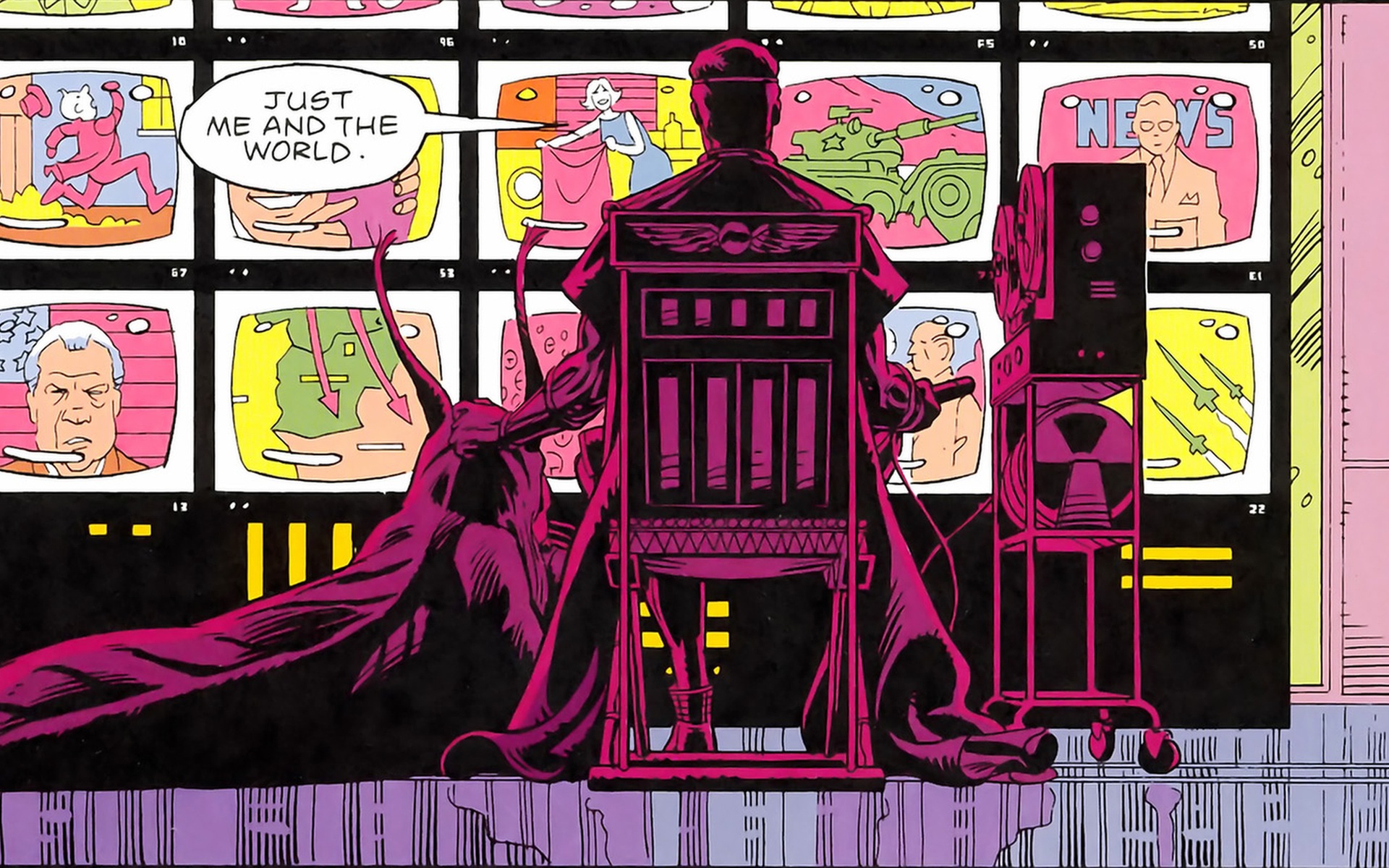

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons may have illustrated this most clearly in Watchmen.

Who watches the… oh, right…

As a parable about the perils of the superhero ideology, Watchmen is clash of five differing perspectives:

- The original Night Owl is an (antiquated) believer in truth, justice, and the American way — a classic hero

- The Comedian is essentially a villain who channels his sadistic violence into acts of heroism — an anti-hero whose ends are achieved by highly questionable means

- Rorschach divorces himself from society and refuses to play by its rules, yet he’s paradoxically the biggest believer in an unwavering moral code — he’s the opposite of the Comedian, in that he breaks the law to uphold his personal sense of justice whereas the Comedian unleashes terror under protection of the cover of law

- Dr. Manhattan goes a step further, divorcing himself not just from society but from reality — he’s the most powerful “hero,” yet he increasingly finds it impossible to adhere to a moral code simply because his consciousness has expanded beyond the need for one

- Ozymandias is the hero as villain — someone who believes that his exceptionalism makes him unjudgeable and unaccountable, yet also the only person capable of saving society from itself

Ozymandias’s plan to “save” humanity is a clear precursor to the “grey area” quest of Thanos in Avengers: Infinity War mixed with the calculated warnings of the Screenslaver in Incredibles 2. But Moore’s take is actually more subversive then Marvel’s or Pixar’s, because Moore never lets Ozymandias (or us) off the hook: he refuses to make Ozymandias a true “villain,” or even depict him as being categorically “wrong.”

Instead, he forces us to ask ourselves: how far should a hero be willing to go in order to defend his unassailable ideals?

And by asking that, in effect, Moore makes us all antiheroes by association.

500 channels and nothing’s on…

America’s post-Kennedy and post-Vietnam rise in cynicism mixed with the detached irony of “nothing really matters” sucked the oxygen out of sincerity and created a breeding ground for anti-heroes who take turns justifying their means to achieving noble ends — or, just as often, avoiding noble ends altogether until it’s cathartically convenient for them to do so.

It’s a bone thrown to our hopeful sense that, when push comes to shove, of course we’ll always do the right thing…

Won’t we?

Anti-Heroes Recast as Heroes

Move over, bub…

The Marvel Cinematic Universe, and Marvel comics before them, stand in stark contrast to the classic comic heroes of DC.

There’s a reason they call Superman “the big blue boy scout”: because he embodies a youthful and innocent belief in the inherent goodness of mankind. Superman, Wonder Woman, Aquaman, Green Lantern, the Flash, Shazam… DC’s most iconic heroes (aside from Batman) all represent classic heroism.

Meanwhile, almost every major Marvel character (except Captain America and Thor) is a compromised hero, or an anti-hero.

Wolverine and the X-Men are mutant outcasts, hunted by the very society they attempt to protect. Iron Man is a sarcastic genius playboy who uses his family fortune earned from creating weapons to start defending the planet instead of exploiting it. Black Widow and Winter Soldier are former assassins who decided to seek redemption by finally playing for the good guys. Dr. Strange is an egomaniac who only became a hero through sheer force of will. And Daredevil is a lawyer by day and vigilante by night who uses his fists to deliver the justice he can’t achieve in court.

To modern audiences, Marvel’s heroes always seem more relatable than DC’s because Marvel’s heroes are flawed and conflicted, just like us. (For example, Wanda Maximoff’s conflicted character arc in WandaVision or the Avengers’ struggle to overcome their own grief in Avengers:Endgame.)

Those same flaws make for magnetic 3-act film stories, because their ultimate catharsis comes from overcoming their internal conflicts in order to achieve their idyllic goals.

But DC’s heroes rarely have defining flaws.

Sheer perfection

Instead, DC heroes’ weaknesses are mostly external — like kryptonite, magic, or the color yellow.

That means they rarely have to change in order to succeed because they’ve been “right” all along.

This doesn’t make for nearly as compelling of a story arc… which probably explains why Warner Bros. has been “Marveling-up” the DC heroes over the past decade, both as a way to make them “dark and gritty” to match the Frank Miller-inspired tone of post Dark Knight-Batman and because they recognize that audiences seem addicted to antiheroes. (See: the joyless “heroism” of Zack Snyder’s DC movies.)

In a similar vein, Jonah Nolan — the brother and collaborator of Dark Knight director Christopher Nolan — used the same tactic on Westworld: in order for the robotic hosts to achieve their own sentience and freedom, the once-virtuous Dolores feels that she must now become a cold-blooded killer. So what if that makes her as bad as the humans who abused her? If it achieves her freedom, it’s justified… right?

RELATED POST:

The problem?

Forcing heroes to become antiheroes is unnecessary, because it ignores the differentiation that makes a pure hero (and those purely heroic ideals) attractive to audiences in the first place.

Here come the neck snapper…

Antiheroes work as a contrast to heroes, not exclusively as replacements to them. Iron Man is interesting when contrasted with Captain America, but he’d be less compelling in a world where every member of the Avengers was a fast-talking quip machine. (The Defenders already tried that; it didn’t work.)

Worse? Without heroes who clearly stand for something, we can’t really tell where the lines are drawn between heroes, antiheroes, and villains.

Batman is defined as much by his costume as he is by his willingness to bend or break the law in order to defend the justice those laws are intended to ensure. He needs the big blue boy scout of Superman to counterbalance him, as a reminder that Batman’s work outside the law is a choice. (Granted, Superman is also bulletproof and Bruce Wayne isn’t, so Batman’s illegal approach could be justified… but Bruce’s endless wealth provides him with his own kind of deathless invulnerability.)

The inescapable popularity and relatability of anti-heroes has also led to a bizarre pop culture development in our post-9/11 world, which is…

Heroes Masquerading as Anti-Heroes

What do you do when sincerity is considered an unrelatable flaw?

You dress it up in black.

Bad bad bad bad boys… make me feel so good..

In the story problem-filled Jurassic World franchise, Owen Grady is infallible. He’s tough, smart, athletic, virtuous, and never, ever wrong… so, naturally, he’s presented as a “bad boy.” He’s not big on technology. He likes the simple things in life. He rides a motorcycle.

Owen is a classic hero, forced to masqerade as an antihero with a Han Solo vest and a Clint Eastwood scowl.

Or take the Deadpool franchise, in which a meta-motormouthed cartoonish assassin — who’s essentially a villain who’s only considered a hero because the people he kills are worse than he is — secretly believes in things like family, love, and protecting the innocent. He just has to hide those values and vulnerabilities behind an insurmountable wall of detached sarcasm… kind of like everyone you’ve ever dated, amirite?

Likewise, the entire Fast and Furious franchise is built around a gang of criminal street racers who also happen to believe that the honor of family bonds are unbreakable. This makes them more virtuous than any of the law enforcement agents they face, and even converts their enemies to their side.

And perhaps the most obvious masquerading “anti-hero” of all is The Rock.

When you’re here, you’re family

Throughout his filmography, Dwayne Johnson has almost always played characters with clear moral codes and “strong daddy” swagger. (Think Roadblock in G.I. Joe, Hobbs in the Fast and Furious franchise, and his one-legged family-defending supersoldier in the weirdly fascinating Skyscraper.)

The Rock is about as classic as an American hero can get. But because we live in the age of the anti-hero, where truth, justice, and the American way is either considered quaint, myopic, embarrassingly sincere, or a weaponizable ideology for extremism, Johnson cloaks his heroism behind the raised eyebrow and scowl of rugged individualism. Will he always do the right thing? Absolutely. He just needs to look like he’s a badass while doing it, because someone told the marketing department that no one likes a kind and gentle Superman anymore.

But life is a pendulum, and the popularity of these faux-antiheroes who smuggle classic hero tropes in the guise of self-interest suggests that the pendulum may be starting to swing back.

So, are we culturally ready for…

The Return of the Pure Hero?

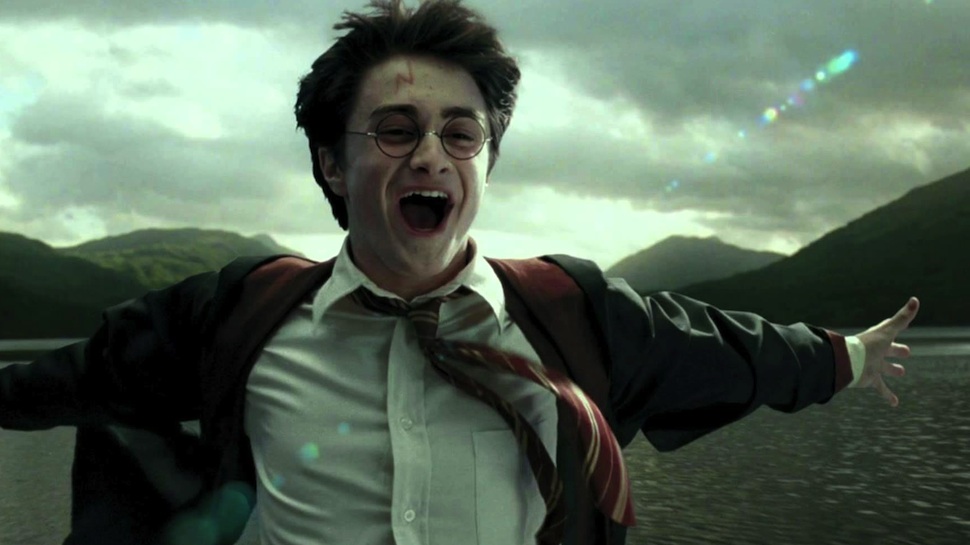

The first sign that audiences never really lost their appetite for unironic heroes was the unquenchable popularity of the Harry Potter franchise.

Harry is a lot of things, but hip and ironic is canonically not one of them.

A whole new woooooooorld…

Instead, Harry Potter is a pure classic hero: he stands for what he believes in, and he only breaks the rules to achieve his goals when it becomes clear to him that the rules and the systems he believes in have become inescapably corrupt. But when he does break the rules, he doesn’t do it ironically, or sarcastically, or while demeaning the idea of a system; he does it in the hopes that a pure and just system can be restored once the corruption is removed.

Harry’s contemporary in Westeros is Jon Snow.

He’s as cold as ice / He’s willing to sacrifice your love

While his unwavering adherence to truth and honor would seem to make Jon Snow one of the less interesting characters in Game of Thrones, the opposite is true: his refusal to bend the rules and his implicit trust in the benevolence of others is not just his defining trait, but it also means he’s taking daily risks in a world where everyone else is willing to lie and betray each other just to stay alive.

And Warner Bros. finally got a DC character right with Patty Jenkins‘s Wonder Woman.

Leading by example

Instead of changing the essence of Wonder Woman’s character, the film leans into it by positioning Diana as a selfless idealist whose core value is protecting others. To hedge their bets, the film surrounds her with a supporting cast of antihero scoundrels whose doubts and flaws serve as a contrast to Diana’s clear-eyed focus.

This results in perhaps the most heroic moment in a DC film yet, in which Diana strides across a “no man’s land” to end a deadly military stand-off and bring peace to an occupied village — the literal Greek definition of heroism.

I am titaaaaniiiiiuuuuum

(Meanwhile, does The Snyder Cut of Justice League depict Wonder Woman any better than the Joss Whedon cut? Well… it’s complicated.)

Even Marvel, who currently owns the global box office after cornering the market on antiheroes, seems ready to lean into classic heroism.

After building their empire on the back of Tony Stark and the Iron Man franchise, Marvel wisely noticed that the counterpoint sincerity of Captain America proved today’s audiences are still willing to show up for characters who proudly and openly live their code. This allowed them to fill Black Panther with forthright statements about honor, justice, and man’s obligation to his fellow man without needing to temper those moments with an ironic wink to the audience.

And maybe the most overtly classic hero of them all is — ironically enough — the one who started Marvel’s DC-disrupting anti-hero movement in comics 50 years ago.

In a not-so-friendly neighborhood.

Tobey Maguire played Spider-Man with a gee-whiz thrill, but the Sam Raimi era of Spider-Man was still filled with sly winks and nods, as if we were all “in on the joke” that Spider-Man was a purist. It was a tentative step toward (and admittedly the truest on-screen incarnation yet of) the character’s irreverent underdog roots.

But Tom Holland‘s version of Spider-Man is notably different.

He’s boyish, whimsical, and seems genuinely awed by what he’s doing as he does it. He’s eager to please, he craves validation, and he’s incapable of refusing to do the right thing — he’s basically a puppy in a costume. And that kind of unabashed joy at being a hero has been sorely missing from superhero films in particular, and in American cinema in general, at least since Bruce Willis‘s pure-hearted grumbler John McClane morphed from underdog to invulnerable over the course of the Die Hard series.

It’s also what makes the final moments of Avengers: Infinity War so powerful: it feels like we just got to see what uncompromised heroism looks like for the first time in so long, only to have it snatched away by the whims of a cruel universe.

But if trends really are a pendulum, we may yet see the return of heroism and sincerity on its own terms, rather than feeling obliged to show up disguised in sarcasm and defensive irony.

Especially if the Avengers have anything to say about it.

How Avengers: Endgame Fulfills the Emotional Arcs of Marvel’s Characters

6 Comments

Abril · August 15, 2023 at 2:59 am

Interesting article, and structured in a digestible way. The Rings of Power is a perfect example of how the mystery box and turning heroes into anti-heroes kills storytelling, causing the biggest culture outcry than The Last Jedi.

Joe · January 12, 2022 at 8:38 pm

I strongly disagree with your second point. Not that it’s wrong, necessarily, just that your point of view is skewed. Mystery box media are, at their core, games. They’re riddles, puzzles to be solved. This gives the audience a feeling that they’re participating in the film, or show, as opposed to being a mere bystander. I guess you could call this an IQ test, in the same way a crossword puzzle is an IQ test. In fact, I would argue that mystery box more closely resembles sports than puzzles on paper. It’s all about being an active participant. So of course there’s a caste system. Any game by its very nature is going to create a caste system of winners and losers. If that upsets you then don’t play, but don’t try to convince others that the game is broken. If you don’t like games then watch something else, because mystery box isn’t for you. But that doesn’t mean people who thoroughly enjoy this genre somehow see themselves as “better,” or “smarter” than you. Your idea that mystery box viewers think they’re better sounds to me like you’ve been on the sidelines your whole life and hate the game because no one let you play, or because you never learned the rules. Just because you don’t like the genre doesn’t mean you can look down on those who do. People who enjoy intellectual stimulation and being a participant in the storytelling experience shouldn’t be shoehorned just because you don’t feel included. So yeah, you’re not wrong. There is a caste system. There is competition. But it’s okay that it exists because it’s a game, after all. And that’s why people love the mystery box genre. Because it’s a game. Games are fun. The only people who say the game is broken are the ones who never have fun playing – or never felt included in the first place.

Abril · August 15, 2023 at 2:56 am

No mystery here. Projection much?

Mohamed · June 12, 2021 at 6:47 am

I Never Like Anti-Heroes Because They Fought Heroes.

I Stand With Heroes Against Anti-Heroes.

Move over bub · February 19, 2020 at 10:50 pm

move over bub

Karim · July 31, 2018 at 4:11 pm

The problem with the notion of a pure hero or villain for that matter is that it leaves no room for compromise, for flexibility. If you want an example of that, just consider the cockroaches that inhabit the Oval Office and even the current Congress. There are a plethora of pure fanatics who are not willing to budge so much as an inch and as a result, nothing can be done and nothing changes. On the other hand, we can’t handle sincerity in society or the real world. We are taught to be in anti heroes and villains with the ends justifying the means at such a frantic pace that there’s simply no room for processing anything much taking time out to actually feel.

I can’t speak for anyone else but perhaps there’s a need for far less defining lines between heroes and villains because realistically speaking – we have a serious shortage of both.