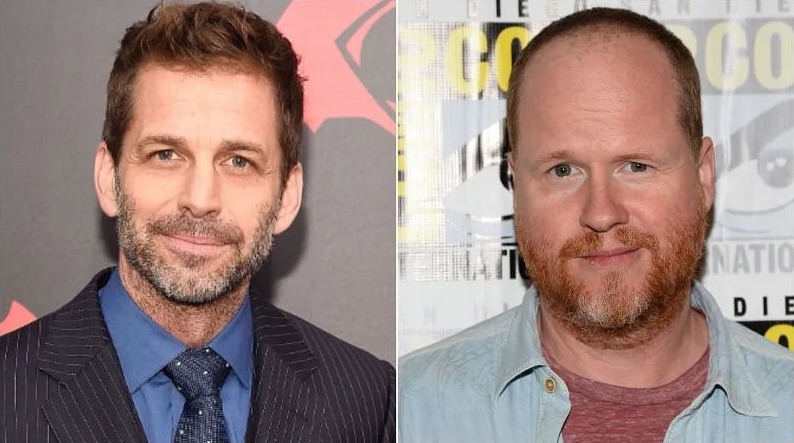

When director Zack Snyder left the Justice League movie unfinished prior to its 2017 release, everyone involved was in a tough spot.

Snyder’s daughter had just died, and he needed a leave of absence.

Warner Bros., which owns DC Comics (home to Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Aquaman, etc.) had a slate of DC films in the works, including Justice League, that had to hit certain release dates in order to generate revenue.

And Joss Whedon, whom WB hired to complete Snyder’s movie, was coming off back-to-back Marvel blockbusters with Avengers and Avengers: Age of Ultron, the latter of which was rife with stories of “creative difficulties” between Whedon and parent company Marvel/Disney.

While it may have seemed like the safest bet to WB at the time, hiring Whedon to finish Snyder’s movie was, in retrospect, probably a bad idea all around.

Not only are their storytelling styles and goals inherently incompatible, but Whedon was already deeply associated with the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). Until they hired Whedon, WB seemed to be actively trying to differentiate themselves from the MCU by giving the reins of the DC Extended Universe (DCEU) to ponderous auteurs like Christopher Nolan (The Dark Knight trilogy) and Snyder. In fact, Snyder’s two prior DC films (Man of Steel and Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice) had already established his particular versions of Superman and Batman as joyless heroes who only help people due to obligation, not inspiration.

Given all of this, it’s no surprise that Whedon’s Frankensteined version of Snyder’s Justice League was so poorly received in 2017. (Granted, the terrible marketing didn’t help.) Whedon fans already had their fill of his schtick from the Avengers films, which made his take on Justice League feel both reductive compared to Snyder’s version and redundant to his own Marvel work. Plus, Snyder’s fans felt he was forced off the movie, so they were naturally resentful of embracing someone else’s completion of his vision.

So in 2020, when WB finally gave in to the years-long petition from Snyder’s diehard fans to “release The Snyder Cut,” it seemed like “justice” for Justice League might actually happen.

Snyder was given $70 million and the freedom to do almost anything he wanted to complete his version of the story. The result is a 4-hour superhero epic that is undeniably Snyder’s vision from top to bottom. Now Snyder gets to feel at least semi-satisfied, his fans get to feel vindicated, and WB-owned HBO Max gets to enjoy tons of free publicity and presumably a few new subscribers as the only place where The Snyder Cut can be seen.

Because Snyder has a legion of fans at his disposal, and because public opinion of The Whedon Cut — and, these days, of Whedon himself — is so low, The Snyder Cut is generally thought to be better than The Whedon Cut by default; that it is an artistic victory simply by virtue of existing at all, given the long and winding road it took to get it here.

With all of this in mind, I finally sat down to watch both versions of Justice League over the past week, and I was shocked to discover something that I absolutely did not expect:

The Whedon Cut actually tells a better story.

I don’t just mean “better” from a subjective “I prefer this version” standpoint. I mean that The Whedon Cut, for all its flaws (and there are definitely several), tells a more efficient, effective, thematically consistent, logically and emotionally coherent story featuring characters with clearly defined arcs of growth and change.

Meanwhile, The Snyder Cut — even with total artistic freedom and an extra two hours of runtime — feels less thematically consistent, coherent, or fulfilling. Its characters barely have arcs or exhibit any signs of meaningful change (although, to be fair, they also express no real desire to do so) and the film is designed around a plot point that can’t help but automatically alienate a number of viewers. And yes, it’s consistent within Snyder’s worldview, but his worldview isnt exactly consistent within itself.

To explain why The Whedon Cut works better at a storytelling level, I’m first going to compare what each movie is trying to accomplish, and then look at specific scenes and elements from both versions of the movie that directly impact their storytelling goals. By the end, even you still prefer The Snyder Cut, I hope you’ll be able to give The Whedon Cut more credit for what it does accomplish than the automatic dismissal it usually receives.

But first, let’s get one quick thing out of the way: neither Joss Whedon nor Zack Snyder was the best choice to tell the story of the Justice League in the first place.

The Wrong Men

If you look at Zack Snyder’s filmography (Dawn of the Dead, 300, Watchmen, Sucker Punch, etc), the dots are easy to connect: he’s an Ayn Rand fan who believes in Libertarianism, Objectivism, and “great man” theory. His men are usually extremely manly men who either represent the law or work outside it in order to stop debased subcultures from rising to power and polluting sovereign exceptionalism.

Crucially, Snyder’s version of Superman and Batman are isolationists who don’t even want to be heroes; they do so out of obligation. Snyder’s Superman is here to protect and rescue the weak wretches of humanity, as if he’s a messiah condemned to save this hell on earth from itself. Meanwhile, Snyder’s Batman isn’t trying to save people but to exterminate threats — including Superman himself, whom Batman has identified as humanity’s greatest threat of all.

With that backdrop from the first two movies in this series, Snyder’s worldview and his renditions of these characters seem entirely ill-suited to the concept of a superhero team-up movie in which a squadron of headstrong heroes learn how to work together in order to defeat an even more powerful enemy. That motivation reeks of altruism and selflessness, which are antithetical to Snyder’s Randian worldview.

But you know who does have a track record of telling stories about a group of outcasts who come together, form a makeshift family, learn to trust each other, and collaborate to stop a powerful threat? Joss Whedon (Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel, Firefly), which is why his take on Avengers and Avengers: Age of Ultron were already so successful for Marvel… and thus, why he was the exact wrong choice to finish Snyder’s uncompleted vision for DC/WB’s Justice League.

The stories Whedon tells tend to have three recognizable traits in common: they’re efficient plot engines, dripping with sarcasm, and bursting with heart — all of which are ideal for a studio tentpole that’s intended to sell fast food and kids’ toy tie-ins.

Snyder’s stories, by comparison, are Herculean trials to be endured by heroes who didn’t ask for this burden but who learn to suffer through it with resigned grace. Snyder’s movies aren’t here to sell action figures; they’re here to get kids hooked on Atlas Shrugged. The emotions that Snyder’s stories seem most comfortable exploring are anger, dominance, paranoia, righteousness, and spite, which are the opposite of what a traditional superhero team-up usually revolves around.

In other words, asking Joss Whedon to finish making Zack Snyder’s movie is like asking Guy Fieri to finish making a dinner that Bobby Flay began. The ingredients may be the same, but each man is going to see their value very differently.

With that said, let’s take a look at the story that each man finally brought to the screen, and then look at how those ingredients were used to varying degrees of success.

What Is Each Version of Justice League About?

While the two cuts of Justice League are about 70% similar in terms of footage, scenes, and storylines, what Whedon does with Snyder’s footage — and what he changes — gives The Whedon Cut a very different narrative purpose than The Snyder Cut.

What doesn’t change is the general plotline of each film, which is:

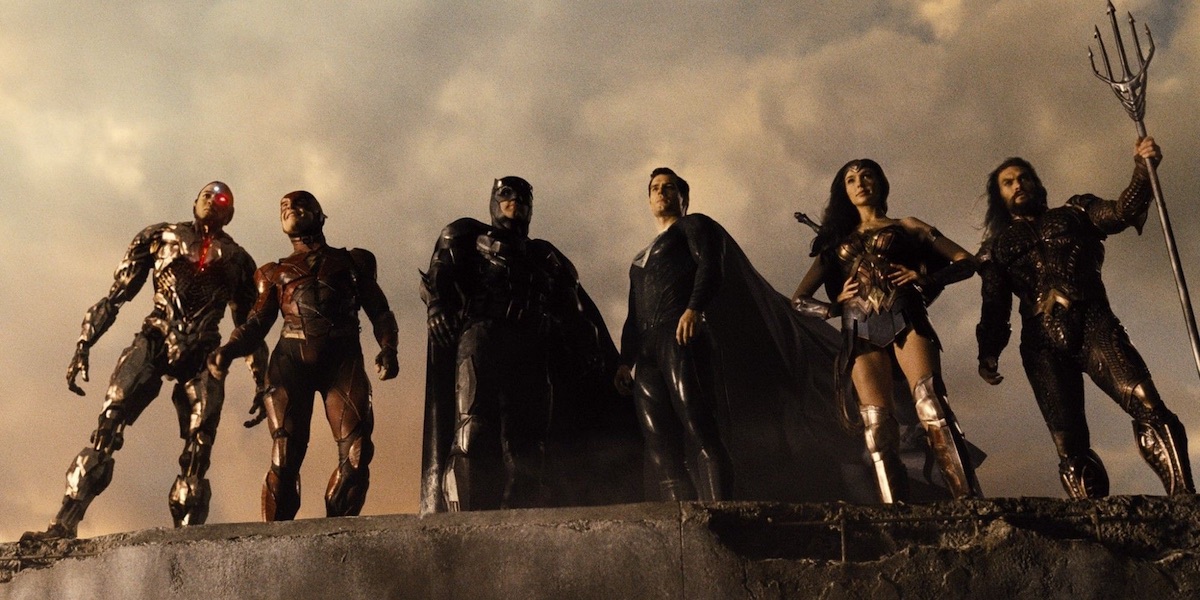

After Superman dies at the end of Batman v Superman, Batman/Bruce Wayne tries to bring together a team of superheroes to fight a growing threat. He’s not yet sure what this threat is, but he knows it’s so big that he can’t stop it by himself. Aquaman/Arthur Curry, Wonder Woman/Diana Prince, Flash/Barry Allen, and Cyborg/Victor Stone each have reservations about joining the team (well, except for Flash; he’s all in), but once they come together they figure out the true nature of the threat: Steppenwolf, a villain from another planet, is trying to find three Mother Boxes that have been hidden on Earth for thousands of years. If he and the parademons he controls can find and unite the three boxes, he can destroy the world.

The heroes try to stop Steppenwolf but he’s too powerful, so they take a risk: they use one of the Mother Boxes to bring Superman back from the dead. At first, Superman has no memory of his past life and he sees the heroes as enemies, but Lois Lane intervenes and helps Superman remember his past and his commitment to protect the Earth. The heroes’ risk pays off, Superman helps them kick Steppenwolf’s ass, and the end of the world is prevented. Afterward, the heroes all go their separate ways, but Batman starts building a Hall of Justice where they can come together again when the need arises. And in a kicker scene, Lex Luthor makes a deal with Deathstroke/Slade Wilson to team up in opposition to the heroes, providing the spark for future sequels.

Okay, so if this plot is essentially the same across both movies, how are they each so different?

It all comes down to thematic intent.

The Whedon Cut (like most Joss Whedon stories) is a tale of flawed individuals who must find ways to overcome their internal and interpersonal conflicts in order to defeat an external threat. Specifically, each of the heroes — and the world at large — is living in the shadow of fear, doubt, and hopelessness after the death of Superman. To succeed, each hero must learn how to trust the others — and themselves — in order to combine their abilities and stop the overwhelmingly powerful Steppenwolf from turning Earth into a living nightmare of fear and suffering. Every story choice Whedon makes supports this goal / arc.

The Snyder Cut (like most Zack Snyder stories) is a tale of righteous individuals whose exceptionalism cannot be questioned, who must learn to actualize the highest form of their innate power in order to accomplish what no one else can. To succeed, they must resurrect Superman — the only being even greater than them — in order to prevent Earth from being enslaved by a foreign power and defend every individual’s sovereign right to make their own independent choices. Every story choice Snyder makes (kind of) supports this goal.

Importantly, while Whedon’s Justice League is about people, Snyder’s Justice League is about heroes who basically become gods. The seeds of this epic worldview were planted throughout the Snyderverse trilogy: In Man of Steel, Superman is essentially God. Thus, Batman v Superman = man vs. God, except that Batman’s prize for “winning” is realizing he was wrong: there are more threats coming than man can stop alone. Therefore, the key to survival isn’t beating God; it’s getting a team of gods together (Justice League) to protect the world.

Now that we’ve established the different thematic and narrative purpose of each cut of Justice League, let’s look at the specific differences that help each director tell his version of the story despite using mostly the same ingredients.

The Major Storytelling Differences Between The Whedon Cut and The Snyder Cut

There are plenty of online resources that compare the differences between these two versions of the film side-by-side. I’m not going to go through them all, but I will highlight the ones that most clearly impact each director’s execution of their vision. (Also, keep in mind that screenwriter Chris Terrio is the sole author of the script that became The Snyder Cut, so some of Whedon’s changes were alterations to Terrio’s choices and intentions, not just to Snyder’s.)

Let’s Start at the Beginning

The Whedon Cut opens with a prologue: a brief clip of Superman being interviewed on the street by two kids who ask him a bunch of excited questions. He mentions that the “S”on his chest stands for hope which, like the bend of a river, is something that comes and goes. “A man I knew said hope is like your car keys: easy to lose, but if you dig around, it’s usually close by.” When the kids ask him what the best thing about Earth is, he stares off into the distance to think before he answers, smiling at all the possibilities… and the clip cuts to black.

The next sequence does a lot of heavy lifting. It frames Batman as the main character, sets up the threat of the parademons right from the very first scene (and makes Batman directly active in attempting to understand and defeat them), introduces the iconography of the Mother Boxes as a related puzzle for Batman and Alfred to ponder, establishes fear as a theme that will recur in various ways throughout the film, and gives the scene’s petty thief a bit of dialogue that encapsulates the story’s overarching problem: Superman’s absence has left the world without hope, regressing toward humanity’s worst instincts, and leaving humans vulnerable to threats that are infinitely powerful. “It’s ’cause they know he’s dead, right? Superman. He’s gone. Where does that leave us?” That’s Batman’s — and this film’s — problem to solve.

This scene is followed by a title sequence that shows the aftermath of Superman’s death from a sociological perspective: newspaper headlines, flowers at his memorial, and an alarming rise in violence targeting marginalized people. In the absence of a unifying hero, we’re back to fighting over our differences.

So, to recap, The Whedon Cut opens with a three-part narrative strategy:

- It establishes Superman as an icon of hope, who is now lost — and, crucially, it depicts him from the perspective of the people who love and are inspired by him

- It establishes Batman as the central protagonist who must solve the problem of a pending alien invasion by defeating a swarm of creatures who feed on fear, which is at an all-time high on Earth since Superman died — an event that Batman is also kinda responsible for

- It shows how Superman’s absence is affecting life on Earth for common people, who now face depression, violence, and other conditions that make fear seem so much stronger than hope

Meanwhile, Snyder’s version opens by re-enacting Superman’s death from Batman v Superman, a.k.a. “the grunt heard ’round the world.” Literally: when Superman dies, his last breath echoes in a seismic ripple around the planet that can even be heard underwater in Atlantis. We see Lois’s tradition of bringing coffee to the cops on duty at the Superman memorial. We see the Kent house, foreclosed and empty, as Martha Kent drives off in a U-Haul. We spend a large chunk of time steeping ourselves in the bleak emptiness of a post-Superman world, like sad teabags. Largely, we do this alone; there is almost no dialogue in this sequence, and little commiseration. Just sad people being sad in isolation.

Already we see the difference in each director’s approach and intentions.

Whedon’s version of this story will be plot-based, character driven, and focused around a pair of themes: coming together and overcoming fear. Meanwhile, Snyder’s version of this story is theme-based, focused on the iconography of exceptionalism, sacrifice, and the eternal quest for righteousness in a world filled with weakness and evil.

Wonder Woman’s Changing Role

In both versions of Justice League, Wonder Woman rescues a group of hostages from anarcho-terrorists who want to plunge the world back into a golden age of fear. But her pivotal line of dialogue at the end of each version of this scene is vastly different because it lampshades what each film is all about.

In The Whedon Cut, Wonder Woman saves the hostages from a hail of gunfire by deflecting every bullet at high speed. The wide-eyed gunman says “I don’t believe it! Who are you?” Wonder Woman looks him in the eye and says “a believer.” Meaning? Unlike these villains who think hope is dead, Wonder Woman believes you can create your own hope.

In The Snyder Cut, Wonder Woman does the exact same thing, but the “who are you” line is cut. Instead, after dispatching the terrorists, Wonder Woman handwaves away all the trauma these hostages have just experienced by smilingly reassuring them that they’re okay and everything’s fine. One little girl asks her, “Can I be like you when I grow up?” To which Wonder Woman replies: “You can be anything you want.” Meaning? Wonder Woman is a benevolent god who is here to save her lambs, and those lambs don’t need to limit themselves by simply wanting to become good; they can grow up to do anything they want.

That’s because in the Snyderverse, maintaining the sovereign independence to make your own decisions is always the most important ideal.

Batman’s Motivation

In The Whedon Cut, Batman is gathering a team of superheroes together because he sees the world falling apart and he believes there are beacons of hope who can make a difference. His quest is framed partly as an ideoligcal investment in rekindling hope, but also as a choice he makes to “undo a mistake,” in his own words. While he previously saw Superman as a threat worth eliminating, he now realizes that Superman was the ultimate beacon of hope, and he’s taking it upon himself to re-light that torch by motivating these other heroes to come together. A large part of his motivation is to assuage the guilt he feels over the Superman-less problem he’s created.

In The Snyder Cut, Batman is gathering a team of superheroes together because he believes a great evil is coming and he needs warriors to defend and protect the world. Assembling this team is his obligation, and something that only he has the means (technological, financial) to achieve. His quest is framed in mythic proportions, and his guilt is something he mostly suffers with in silence, if he acknowledges it at all.

In both versions, Aquaman and Cyborg are reluctant to join. But Whedon’s version adds extra dialogue between Bruce Wayne and Arthur Curry that establishes their differences in perspective while also giving each of them a valid point: they disagree as equals. (“Doesn’t mean I’m wrong.”)

In Snyder’s version, there’s less dialogue, which gives the impression of a wider ideological gap between them. When Aquaman swims away, the women on the shore sing a sad and lengthy folk song about him that positions him as a mythic hero in their eyes. This is because it’s crucial to Snyder’s vision that every hero must seem larger than life at all times, as gods among men who only deign to save humanity when it suits them.

Cyborg’s reluctance to join the team is depicted even more differently in Whedon’s version, and here we get into one of the biggest storytelling changes between the two movies:

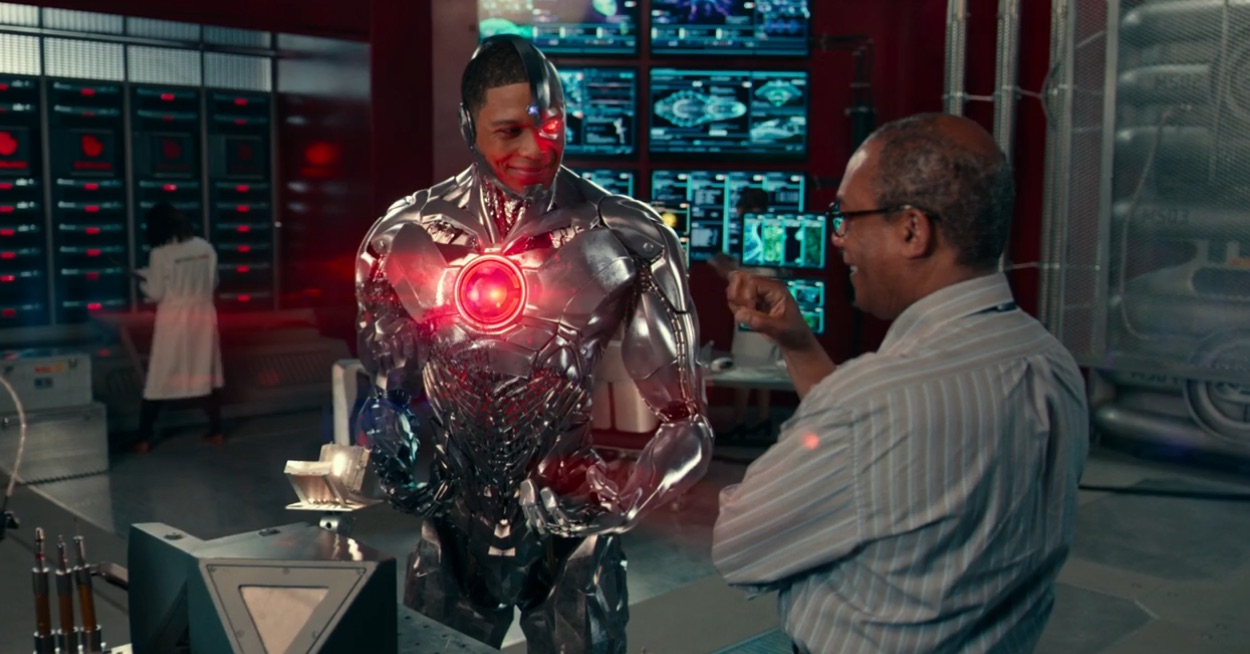

A Tale of Two Cyborgs

Ray Fisher, who plays Victor Stone / Cyborg, has very publicly criticized Joss Whedon, Geoff Johns, and several other WB/DC execs for what appears to be hostile, racist, and dismissive treatment during Whedon’s reshoots of Justice League. Combined with other reports of Whedon’s problematic, sexist, and sometimes abusive behavior, it’s likely that Fisher truly did have a terrible time working with Whedon, and that he felt a much closer, more collaborative, and more supportive working relationship with Snyder.

This is a shame for many reasons, and if there’s one actor who I hope feels vindicated by the release of The Snyder Cut, it’s Fisher, since he’s publicly said he had more input over Snyder’s interpretation of the character than Whedon’s. But the irony is, from a story perspective, I think that aside from a few cringeworthy dialogue choices, The Whedon Cut actually serves Cyborg better as a character and Fisher better as an actor, because Whedon’s version gives Cyborg more emotional and narrative range.

Snyder’s version of Cyborg is rooted in anger. He’s upset at his father Silas for never being around. He’s mad that his father wasn’t present at the accident that killed his mother and which nearly killed him. And he’s furious that his father rescued him from the brink of death by turning him into what he sees as a mechanical monster.

Whedon’s version of Cyborg is still angry for all these same reasons, but he’s also given a pair of additional traits that make his character feel more fully formed and more proactively motivated than Snyder’s version.

First, he’s struggling to understand the “voices in his head” and his newfound abilities, which we quickly learn were bestowed by one of the Mother Boxes. Victor points out that after Superman died, people began worrying about where the next alien threat might come from… and now Victor is worried that it might be him. Feeling trapped in a body that might betray you is a more complex character angle than paternal resentment alone, and it also creates a direct interpersonal conflict with Aquaman, who’s never quite sure if Victor should be trusted.

Second, Victor is shown as being more proactive in learning how to use his powers and defend himself in Whedon’s version than he is in Snyder’s, where Silas basically gives him a user manual to walk him through his newfound abilities… and there are a lot of them.

The Snyder Cut includes a lengthy voiceover where Silas explains every one of the powers he’s bestowed upon Victor — including limitless control over the world’s entire nuclear arsenal and all of its money — followed by a sequence where Victor spies on a woman, decides she deserves more money in her life, and gives her an extra $100,000 from Gotham Bank, proving that Victor — like all of Snyder’s heroes — is above the law in every way. In the Snyder Cut, Silas essentially gives Victor enough power to be a technological, military, and economic god, putting him in the same mythic league as the other heroes.

But in Whedon’s version, Silas didn’t architect everything about Cyborg; he simply plugged Victor’s dying body into a Mother Box out of desperation. As a result, neither of them fully knows what Victor can do now. This uncertainty adds to Victor’s existing resentment and anger at his father, as well as giving the audience a chance to root for Victor to master his abilities over time — something he doesn’t need to do in Snyder’s version, where he becomes the master of his powers all at once. Whedon also shows that Victor is quickly figuring things out when he hovers menacingly above his dad during an argument (“Couldn’t do that yesterday”), and when he’s shown monitoring and scrambling Bruce and Diana’s attempts to find him.

Structurally, Whedon explores Victor’s internal doubts and interpersonal conflicts through dialogue and action. His uncertainty is usually intertwined with a story problem that must be solved, or a character flaw that must be resolved. Meanwhile, Snyder’s version of Cyborg doesn’t have character flaws. He was a perfect student, athlete, and hacker with a heart of gold, who has now been granted immeasurable power by his father and a mandate to use it for self-actualization.

Snyder’s version of Cyborg is also always, always, always angry.

He’s angry when he’s upset. He’s angry when he’s joining the team. He’s angry when he’s fighting alongside the team. He’s angry when they’re putting a plan together. He’s angry when they’re losing, or when they’re winning. His depicted emotional range is a grunting flatline, which makes him identical to Batman, Aquaman, Deathstroke, and the other righteous men who dominate the narrative.

Whedon’s version of Cyborg is often justifiably angry, but he’s also shown to be scared, surprised, awed, excited, defensive, desperate, and elated. He spends the first third of the movie clad in a grey hoodie that hides his mechanical body, only removing it when he finally joins the team and embraces his new identity as something he no longer feels ashamed of. This makes more sense for the character’s journey than Snyder’s version, who alternates between wearing a hoodie and stomping around in full mechanical display. That seems more like an excuse to burn through FX money than a concious choice related to the character’s inner state of mind.

With Snyder’s version of Cyborg becoming an overnight master of his domain, Flash becomes the only hero in the group with something resembling a growth arc… except Snyder and Whedon disagree about where that arc is headed.

Flash, and Snyder’s Problem with Saving People

In The Whedon Cut, Flash has a panic attack before their first big fight with Steppenwolf. He explains that he’s never actually been in a fight before; he doesn’t know what to do. Batman, in a moment of fatherly mentorship, says: “Save one.” Just get in there and save one hostage. If Flash can do that, everything else will start to click. It’s a human moment that reminds us our heroes are still human too.

In The Snyder Cut, where heroes are never allowed to show weakness or simply be human, Flash doesn’t have this conversation; that was a Whedon addition. But he also technically doesn’t save any of the hostages; not directly. Instead, he guides them to a stairwell and then just… runs up and down it, acting more like a traffic guard or pep talker while the hostages essentially save themselves.

Why?

Because Snyder’s movies have a strange relationship with the idea of saving people.

Granted, the whole reason Batman is assembling the team is ostensibly to save the world, and the world includes people. But Snyder’s heroes rarely seem happy when they’re saving individual people.

When Aquaman saves a sailor whose boat is sinking, he’s visibly upset that he has to do it and yells that the man should “respect the ocean” next time. When Flash saves Iris during a meet-cute in The Snyder Cut, his gentle hands-on slow motion assistance comes across as unsettlingly voyeuristic. And when Cyborg saves a cop during Superman’s rampage, he growls “maybe you should get out of here.”

To Snyder’s godlike heroes, humans are only ever in the way.

The Movie’s Biggest Problem

More than anything else, the resurrection of Superman is the storytelling flaw that renders both versions of this movie off-puttingly problematic.

A plot that depends on the heroes literally playing god will obviously leave a bad taste in many people’s mouths by default. After all, digging up a grave so they can electrocute the body back to life sounds more like the scheme of a supervillain than a hero. Because of this, both versions of this film were likely doomed from the conceptual stage, since there’s no way Whedon could have edited around this plot point even if he’d wanted to. And judging from the changes he does make, it’s pretty clear he was as uncomfortable with this plot twist as a lot of viewers were.

That’s why Whedon reshot the entire “hatching the plan” scene, and the gravedigging scene.

In The Whedon Cut, the team collaboratively stumbles on the idea of using a Mother Box to resurrect Superman, which they believe is their best chance to defeat Steppenwolf. Aquaman thinks it’s a bad idea, but Diana is downright opposed to it.

Diana: “What if he doesn’t want to come back? What if he’s at peace?”

Bruce: “He’ll get over it.”

The two of them argue about ethics, which Bruce assures her Steppenwolf isn’t thinking about at all. They also pick away at each other’s insecurities about the risks of death — Diana losing Steve Trevor, and Bruce clearly grasping for redemption after his hand in the death of Superman. Whedon’s version of this scene addresses all of the moral quandaries a resurrection plot needs to tackle in order for the heroes to not feel like monsters in the eyes of the audience.

The Snyder Cut addresses none of these issues. Instead, the team uniformly comes to the idea of using the Box to resurrect Superman while barely addressing any of the legal, ethical, or moral issues that decision entails. They spend more time talking about the physics of getting the plan to work than about whether they should do it in the first place. That’s because it’s unthinkable that Snyder’s version of these characters would second-guess themselves.

And speaking of second-guessing…

Lois and Martha

In The Whedon Cut, Martha Kent and Lois Lane have a friendly discussion in a break room at The Daily Planet. Each of them is still obviously struggling with the absence of Superman/Clark Kent in their lives, but they’re each also moving on in their own way. Importantly, Lois is still working, but she’s just doing “fluff pieces,” not actual journalism — she isn’t ready for it yet. Martha is understanding, but she also encourages Lois to get back to doing what she loves because she’s so good at it.

The message in Whedon’s version of this scene is that while loss is difficult and grief is valid, we can’t let it derail us from living our lives and sharing our gifts with the world.

In The Snyder Cut, Martha and Lois have a sad, somber discussion in Lois’s apartment, which she evidently hasn’t left in days. When Martha tells Lois that the Kent farm has been foreclosed, Lois offers to help but Martha refuses; she’s not here for a handout. Instead, Martha encourages Lois to go back to work — not because it’s what she loves, or what she’s good at, but because it’s her obligation. Lois, drained from grief and the pointlessness of living without Clark, agrees to consider it.

… and then, in a twist that (IMO) drastically undercuts the scene, Martha exits Lois’s apartment and it’s revealed that it wasn’t Martha at all, but the shapeshifting superhero Martian Manhunter posing as Martha in order to motivate Lois. “The world needs you too, Lois,” he says, to… uh, to no one, really; so: to us.

The message in Snyder’s version of this scene (besides “never accept a handout”) is that Lois has a duty to continue working, and it’s time she gets back to it. But having this advice come from someone else posing as Lois’s spiritual mother-in-law feels distastefully deceptive, as though Lois is being manipulated amid her grief. It reads as a very disempowering scene, which I suspect is the opposite of what Terrio and Snyder intended. (It also, by revealing Martha isn’t actually Martha, means The Snyder Cut fails The Bechdel Test, but that’s another issue for another day.)

But we’re not done with Lois just yet, because…

Superman Returns!

In both versions of the film, Cyborg and Flash work together to electrocute Superman’s corpse and bring him back to life with the power of the Mother Box. But Superman returns with none of his memories intact, so he views the heroes as a threat and proceeds to whip their collective ass.

In The Whedon Cut, Alfred foresees this possibility and asks Bruce what he intends to do if things go wrong. Bruce replies that he’ll have “a contingency” for that, which he refers to as “the big gun.” We may presume he means a kryptonite gun, but in actuality he means Lois Lane. Just as Superman is about to kill Batman, Bruce asks Alfred to bring in the big gun and Lois Lane steps into frame. Seeing her jolts Superman out of his murderous stupor; they embrace and fly away to somewhere safe where he can collect his thoughts.

In The Snyder Cut, Lois just so happens to be walking past the Superman memorial that morning on her first day back at work after her inspiring conversation with “Martha.” Batman didn’t have a backup plan to avoid getting killed, but luckily Lois yells to Superman at precisely that moment and he recognizes her, and they fly off together.

The purpose of the scene is the same in both films, but Snyder’s robs Lois of her agency by making her appearance on the scene a matter of incidental luck. Whedon’s version is actually a better validation of Snyder’s characterization of Batman as a hyper-planner, and it implies that Bruce must have shared his plan with Lois and asked her to be there, which makes her involvement a conscious choice on Lois’s part rather than a matter of Martian Manhunter-induced happenstance.

The Final Showdown

In both versions of the movie, the heroes defeat Steppenwolf and save the world from being destroyed by the unity of the Mother Boxes. But how they do it is markedly different.

In The Whedon Cut, each hero gets a spotlight moment in the boss fight:

- Batman’s firepower takes out the protective grid around the Mother Boxes, which allows the other heroes to storm Steppenwolf’s lair while Batman lures the parademons away with a diversion

- Wonder Woman momentarily becomes the team’s leader despite her discomfort at asking people to potentially sacrifice themselves for the greater good

- Aquaman comes to trust Cyborg when Cyborg saves him from certain death

- Flash and Superman step away from the main battle to save the lives of innocent people trapped in the unity’s radius

- Cyborg and Superman work together to split the three Mother Boxes apart and stop the unity from taking hold

At a pivotal moment, Cyborg explains to Superman that detaching the unity will create a massive energy surge, “but I think we can take it.”

“I hope so,” says Superman. “I like being alive!”

With his plan for world domination foiled, Steppenwolf then gets his ass beat so badly that he becomes legitimately afraid of the heroes’ power… which is when his fear-eating parademons turn against him and swarm him just as he’s teleported back to his home planet.

Afterward, as the unity recedes and the world around them returns to normal, nature begins reclaiming the malevolent energy that had been surging through the environment, visually representing the triumph of hope over fear.

Meanwhile, the heroes in The Snyder Cut take a slightly different path to victory. That difference begins with Batman’s movie-long characterization in both films.

In The Whedon Cut, Bruce is worried almost the entire time about whether or not his plan will succeed,but in The Snyder Cut, Bruce tells Alfred he’s not worried. Why not?

“Faith, Alfred.”

Faith in what? In himself? In Superman? In good karma? In the long moral arc of justice? In the inevitable righteousness of his own infallible plan? Whatever the reason, Snyder’s Batman enters the endgame of his plan against Steppenwolf feeling very confident that the team he has assembled will win.

And yet, ironically, they don’t.

Not at first.

But luckily, Bruce recruited the Flash, and the Flash has the ability to run faster than time. When the team initially fails to stop the unity from occurring, Flash pushes himself to run faster than he’s ever run before, giving himself the ability to rewrite the past and change the future. Which he does. The heroes win, and Wonder Woman kills Steppenwolf for good measure.

Thus, if we compare the lessons learned and the arcs traveled by the heroes in both films…

In The Whedon Cut:

- Batman overcomes his guilt and makes up for his past mistakes by assembling a team that will protect the world

- Wonder Woman overcomes her doubts and learns to become a leader

- Aquaman overcomes his isolationism and learns to trust his teammates

- Flash overcomes his nervousness and learns how to become a hero

- Cyborg overcomes his fear and anger and learns to trust himself, makes friends, renews his relationship with his father, and finds a new purpose

- Steppenwolf is undone by his own hubris, ultimately overwhelmed by his fear-eating parademons when the combined might of the Justice League makes him afraid for the first time in eons

In The Snyder Cut:

- Batman is right all along

- Wonder Woman is also right all along

- Aquaman temporarily learns to work with others

- Flash pushes his limits further than they’ve ever gone before… twice

- Cyborg overcomes his resentment toward his father but is otherwise right all along

- Steppenwolf is mocked and maimed by Superman, then beheaded by Wonder Woman

In other words, in The Whedon Cut, the heroes win by learning how to overcome their flaws and work together as a team, while in The Snyder Cut, the heroes win by learning how to master death and time itself.

Slightly different vibes.

(Also, in The Snyder Cut, Flash and Superman never step away to save anyone because the battle is occurring in an unoccupied zone. Once again, despite it being a story about “saving the world,” the humans who comprise the world are largely absent.)

The Aftermath

The Whedon Cut wraps things up with a happy montage, in which the heroes are back to being heroic separately while also tying up their emotional loose ends:

- Bruce buys the bank that foreclosed on the Kent farm so Clark’s family can have it back

- Bruce also begins renovations on what will become The Hall of Justice: “A big table with six chairs” — “with room for more,” Diana adds

- Wonder Woman stops another crime and then takes a moment to chat with some kids at the scene, which pays homage to the Superman scene that opens the film and keeps her “I’m a believer” theme of inspiring others alive

- Aquaman returns to the sea

- Victor shows off his increasing mastery of his powers to his dad, in a happy bonding moment that shows their relationship is improving

- Flash celebrates getting his new criminal justice job (“I got a recommendation from a friend” — presumably Batman or Commissioner Gordon) which gives Barry and his imprisoned father the hope that Barry might someday be able to find a way to get his dad out of prison after all

This montage is narrated with a voiceover from Lois, who seems to be typing a brand new feature article for The Daily Planet:

“Darkness — the truest darkness — is not the absence of light; it is the conviction that the light will never return. But the light always returns, to show us things familiar — home, family — and things entirely new, or long overlooked. It shows us new possibilities and challenges us to pursue them. This time, the light shone on the heroes, coming out of the shadows to tell us we won’t be alone again. Our darkness was deep and seemed to swallow all hope. But these heroes were here the whole time, to remind us that hope is real, that you can see it. All you have to do is look up in the sky.”

Thus, the Whedon Cut ends by showing us that Lois, too, has healed from these events. She’s found her voice and returned to doing the work she loves and excels at. The hope that the film has been searching for is back, and like the opening scene, the focus isn’t on the heroes but on the people they inspire.

Meanwhile, The Snyder Cut inverts this montage in several ways:

- Bruce still agrees with Diana’s addendum to his table-and-chairs plan, but Snyder adds one more crucial line of dialogue for Bruce: “With room for more… God help us”

- Instead of stopping a crime, Wonder Woman returns to reclaim the Amazons’ ancient arrow that alerted her to Steppenwolf’s threat — an arrow that was fired by her mother earlier in the film

- Back at the fishing village he protects, Aquaman tells Mera and Vulko “I gotta go see my father” — which is interestingly worded as an obligation, not a desire

- Flash still celebrates getting his new criminal justice job, but the line of dialogue that refers to it being the product of “a recommendation from a friend” has been deleted — Snyder’s heroes don’t ask for help because they don’t need it; they accomplish their goals on their own

The biggest difference is the voiceover, which belongs not to Lois but to Silas Stone. While Silas is still alive at the end of The Whedon Cut, he sacrifices himself in The Snyder Cut, in a move intended to “stamp” the final Mother Box with a heat signature that Cyborg can trace after Steppenwolf takes it. As a result, Victor is alone at the end of The Snyder Cut, listening to a recording that Silas left for him:

“Now, let me speak to you from my heart, not as a scientist but as a father. Your father, twice over. I brought you into the world and back to it. You can’t imagine how proud I am of who you are, and always have been. So many years I’ve wasted with you, so many wrongs I’ve left un-righted. Everything breaks, Victor. Everything changes. The world is hurt. Broken. Un-exchangeable. But the world’s not fixed in the past. Only the future. The ‘not yet.’ The now. The now is you. Now — now is your time, Victor. To rise. Do this. Be this. The man I never was. The hero you are. Take your place among the brave ones. The ones that were, that are, that are yet to be. It’s time you stand. Fight. Discover. Heal. Love. Win. The time is now.”

While Lois’s voiceover in The Whedon Cut is about finding and embodying hope, Silas’s voiceover in The Snyder Cut is about honoring your obligation to fix a broken world.

Again, slightly different vibes.

BONUS: The Burden of Parenthood

Although this aspect is almost entirely missing from The Whedon Cut, The Snyder Cut (and basically Snyder’s entire filmography) are about the twin themes of Duty and Parenthood.

Cyborg’s character arc is all about his father. Batman’s character arc is as the “godfather” of this group of heroes, whom he brings together to protect everyone else; he gives Cyborg a moment of fatherly support (“She was made to fly.” / “So are you.”), and his post-climax dream sequence is a nightmare about a world where the heroes lost — where he wasn’t a sufficient father and leader, where he’s reminded of his parents’ death, and the death of Robin, signifying his failure as a dutiful protector. Superman comes back from the dead to protect his adopted planet and finds out he’s (apparently?) about to become a father with Lois. Flash dedicates his life to exonerating his wrongfully-incarcerated dad; every choice he makes is in honor of his father. Wonder Woman’s mother worries about her from afar. Aquaman doesn’t have much of a character arc, but it involves living up to the expectations and obligations of his parents, who sacrificed so much for him; after the final battle, his first action is to go see his father, which he does without an inkling of happiness.

In Snyder’s view, the world is filled with evil, and it would fall into ruin if not for the heroes who do the thankless work of protecting us from that evil. It is a never-ending battle, and none of the heroes seem to take much joy in it. Like parenthood, the duty of protection is a joyless obligation, occasionally punctuated by stern but silent pride… until the next crisis.

Conclusion

To appreciate either version of Justice League, we need to be honest about the inherent limitations of the project as a whole.

Zack Snyder wanted to make a visual opera about the unbearable weight of heroism, expectation, and obligation, designed around a graverobbing resurrection plot. Amid challenging personal and creative strife, Warner Bros. asked Joss Whedon to step in and remix Snyder’s operatic dirge into a poppy Top 40 hit that could sell merchandise tie-ins. Whedon’s stitch-up job was ultimately a thankless task that failed for multiple reasons: the marketing was terrible, the tone was divergent from what Snyder had conditioned DC fans to expect, it felt too much like an MCU movie to seem original, Whedon developed his own bad karma during production, and some of the story’s central plot points are unavoidably problematic.

Only by looking more closely at the ingredients Whedon was handed can we actually appreciate how well he was able to execute on the studio’s request while delivering a film that works better in retrospect than it did at the time.

The Snyder Cut is a lot of things.

It’s the culmination of one director’s vision of an epic superhero trilogy.

It’s a reclamation of that vision from a studio who had assigned another director to warp it into a different vision entirely.

It’s a masterclass in the ways that editing can change the meaning of scenes, sequences, and entire films.

It’s one of the most visually aggressive films of the past decade.

It’s a rare example of an ensemble film filled with mostly static characters.

It’s overlong, filled with clunky exposition, and conveys an isolationist tone that seems to be at odds with its foundational concept as a story about learning to work together.

Above all else, it is undeniably A Zack Snyder Movie.

But The Whedon Cut is a lot of things too.

It’s a bizarre hybrid of two directorial styles that could not be more diametrically opposed.

It’s a sitcom sensibility stapled atop a tone poem.

It’s a story of hope and change, where the heroes never lose sight of who they’re fighting for.

It’s a collection of glib one-liners and joyful moments that frequently work well but occasionally misfire so badly that they threaten the credibility of the entire narrative.

It’s closer in sensibility to the heroism that traditional DC fans likely expect from these iconic characters.

It’s a tighter, more efficient, and more narratively and thematically cohesive story that sacrifices grandiosity for relatability.

Above all else, it is neither a Zack Snyder movie nor a Joss Whedon movie, but a rare cinematic specimen that no one can truly claim ownership of. (Not that anyone really wants to.)

But maybe we can give it credit where credit is due: as imperfect as The Whedon Cut is, The Snyder Cut now helps us understand what a unique and underratedly satisfying accomplishment Whedon’s version actually is, on its own terms and — to paraphrase Silas Stone — in its own broken way.

If You Liked This Post, You May Also Like…

How Avengers: Endgame Succeeds on the Strength of Marvel’s Characters

Why Black Sails Has One of the Best Main Characters in TV History

0 Comments