In the final episode of Game of Thrones, showrunners D.B. Weiss and David Benioff finally pulled off their biggest surprise of all:

They nailed the landing.

Despite all the storytelling problems that plagued this final season of Game of Thrones — from bad dialogue to sudden plot armor to sadly disappointing endings for major character arcs — the series ended on a deservedly melancholy note. The tone and lessons from its final chapter are an entirely fitting ending for author George R. R. Martin‘s cautionary tale of power, persuasion, and possibility.

In memory of the show’s eight seasons, here are eight reasons why the Game of Thrones finale works so well.

WARNING: SPOILERS AHEAD for the last episode of Game of Thrones, and the series.

You Can’t Truly Judge a Story Before It Ends

Despite several years of fanboy second-guessing that reached a fever pitch this season, it turns out this story has been in far more capable hands than it may have seemed.

In fact, before I say anything else, I strongly recommend watching this video.

It explains the crucial difference in storytelling structure between the show’s early seasons and its later seasons, which Weiss and Benioff had to write from Martin’s loose outline. (Honestly, once you get past the video’s self-referential setup, this is the best Game of Thrones writing analysis I’ve ever seen.)

In light of all the fan frustrations, one of the most gratifying “twists” is that it turns out Weiss and Benioff knew what they were doing all along. They may have rushed or stumbled at a few points along the way, but in the end, the dots connected and the ending feels fulfilling at all three levels: plot, character, and theme.

For a story this huge, that’s a massive accomplishment all by itself.

A Palpable Sense of Dread

The first third of this episode was an expertly-designed vice grip.

After the destruction of King’s Landing, Tyrion and Jon each go on their own journey through the ashes. Jon finds Grey Worm executing more Lannister soldiers who had attempted to surrender, which offends his sense of honor. Tyrion finds the bodies of Jaime and Cersei, which personalizes his epic sense of loss.

Both men know that they’re going to have to take action against Daenerys — and the episode builds that tension, layer upon layer, until their odds are insurmountable and their choices are inevitable.

The moment when Tyrion throws down his Hand of the Queen pin, and the Unsullied — who had been stamping their pikes in solidarity with Dany’s announcement of unending war — just… stop? That sudden silence was as powerful a depiction of the stakes as any closeups could have been.

Likewise, when Jon approaches the throne room only to be stopped by an exhausted Drogon rising from the ashes… these are the larger-than-life moments that remind us not just why we love the spectacle of Game of Thrones, but also why we care so much: because the stakes are massive.

Poetic Justice

Ultimately, Dany did break the wheel — she just had to sacrifice everything to get there.

After eight seasons, she was finally able to touch the Iron Throne that her dragon-riding ancestor Aegon the Conqueror had built through Targaryen fire and blood centuries earlier. Her arc had come full circle. She had achieved everything she’d ever wanted… but, in true Game of Thrones fashion, she couldn’t keep it.

Meanwhile, Jon never wanted the throne. He never wanted to be Lord Commander of the Night’s Watch either. Or the King in the North. Or a bastard. All of these birthrights and titles and labels were assigned to him by others, by laws and rules and the political games that other people play. Yet, in the end, Jon did what he had to do, because his defining traits have always been loyalty and honor — and, in the end, his loyalty to his ideals required him to be disloyal and dishonorable to his own oath.

In retrospect, Drogon melting the Iron Throne is the only way this story about power and ambition could have ended. And it’s doubly poetic that the character who had the foresight to do what no one else ever would have is the only character who never wanted the throne, and all it represented, in the first place: the dragon who never really had a say, until now.

“Uncle, Sit Down”

The cultural debate over whether Game of Thrones is feminist, misogynist, realistic, or exploitative will probably never end.

But I believe Martin has always intended for this story to serve as a feminist repudiation of the male power fantasy that fuels most “chosen one” fantasy tropes. Ending his story by trading in a throne for a council of representative government that includes four women in a kingdom so often ruled by male heirs is the clearest sign that Martin favors humanism over tradition.

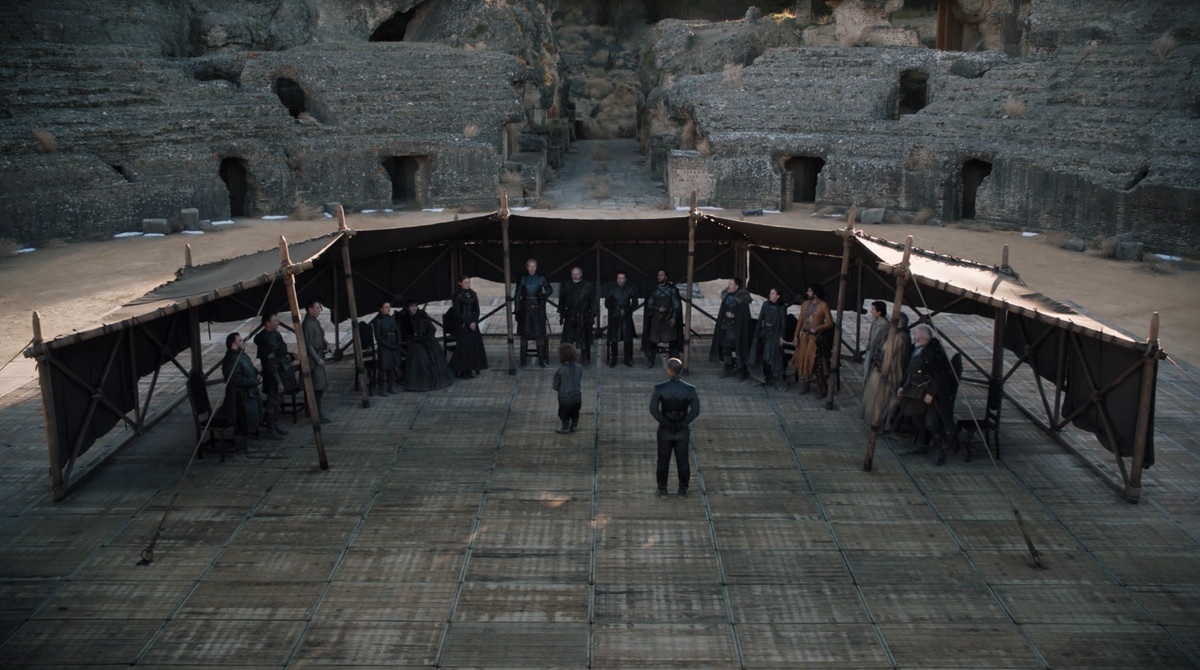

This is made explicit when Sansa cuts off Edmure Tully’s long-winded attempt to nominate himself as the new king with three simple words: “Uncle, sit down.” It’s a signal that the times are changing, and that simply being an old white man with a title granted by other old white men isn’t enough to lay claim to anything anymore.

In the larger sense, the last of the Starks — Sansa, Bran, and Arya, who would normally not be in positions of power — are the only three characters who end the story with true decision-making agency. Bran the Broken is named king of the seven… er, six kingdoms. Sansa declares the North will be its own nation, with her as its queen. And Arya forsakes her titles to travel the world and chart new maps for worlds that have yet to be written.

If that’s not an indication that Martin believes in the inevitability of progress, I don’t know what is.

“Satisfying” Doesn’t Need to Mean “Happy”

The end of Game of Thrones isn’t happy, but it is earned.

In the end, no one is entirely right or wrong, which is true to the theme of Martin’s complex and frequently subjective tale of right vs. wrong, good vs. evil, and choice vs. destiny.

Dany doesn’t want to lose the game of thrones… but her victory is what makes her dream of breaking the wheel possible by others.

Tyrion doesn’t want to serve as the Hand of the King… but it’s better than being executed.

Grey Worm and the Unsullied want justice for Tyrion and Jon’s treason… but they’ll have to settle for sailing to Naath and living Missandei’s dream of freedom without her.

Jon doesn’t want to do… well, pretty much anything he ever did, really. And in the end he’s made a politically sacrificial lamb so that the rest of the world can be better off.

In the end, no one gets everything they want. As Tyrion notes, “no one’s entirely happy about it — which makes it a good compromise.”

And that might be Martin’s most subtle lesson of all.

Bookends and Mirrors

For all its narrative sprawl, the entirety of Game of Thrones came down to Jon and Tyrion in a room.

This last episode of the show bookends the first episode both structurally and thematically, which helps tie up our subconscious loose ends.

The series opens with White Walkers decimating a wildling camp and the Night’s Watch ranger who lived to tell the tale being executed by Ned Stark for desertion of duty while Bran, Robb, Jon, and Theon watch. It ends with Bran, our first point-of-view character who was pushed from a window to his near-death in the very first episode, now ascending to become the ruler of Westeros while Jon, whose actions led to an alliance with the Wildlings and the destruction of the White Walkers — thereby making the Night’s Watch irrelevant — leading a band of wildlings north of the Wall, where people can finally be truly free.

It’s also worth noting that each of the surviving Stark children became “better mirrors” of their mentors on the show, thanks to the influence of Ned Stark, who taught all of his children the value of duty, honor, and staying true to your own convictions.

Bran may be the King of Westeros and the Three-Eyed Raven, but he’s also an explorer who won’t be constrained by titles or expectations — as he proves when he suggests he may be able to find Drogon when no one else can.

Sansa, who learned how to play the game better than anyone by studying and learning from the wisdom and mistakes of Cersei, Littlefinger, and even Ramsay Bolton, rose to the challenge of leadership and forged a new independent future for her people. She’s shrewd… but with honor.

Arya won’t be married off as a lady for another house’s political benefit; she’ll forge her own path across the sea (not unlike Daenerys did before her). Her tomboy autonomy is a distillation of Syrio Forel, The Hound, The Brotherhood Without Banners, and the Faceless Men… but with honor.

Perhaps most interestingly, Jon’s journey ends up mirroring Jaime’s. Both men struggled with the limits of titles. Both men became great warriors. Both men became kingslayers on the steps of the Iron Throne, slaying a Targaryen to save the innocents at the expense of their own reputation. But while Jaime couldn’t break his own wheel — his love for Cersei — Jon gets one more chance at a fresh start up north. He’s the son of many “parents” — Ned Stark, Catelyn Tully, Lyanna Stark, Rhaegar Targaryen, Jeor Mormont, Mance Rayder, and even Stannis Baratheon — but he’s ultimately his own man.

The Greatest Power Is Choice

For a story that revolves around laws, rules, and traditions, the drama in Game of Thrones depends on the choices each character makes within that framework.

Should Jon tell Sansa and Arya about his true heritage, even though Dany warned him it would be the end of everything? As Bran says, “It’s your choice.”

As Jon is about to leave Tyrion for the final time, Tyrion challenges him to take action. “What does it matter what I do?” Jon asks. “It matters more than anything,” Tyrion replies.

And when Jon confronts Dany over her war crimes, and she assures him that it’ll all be better once she’s the ruler of the world, essentially replacing all tyrants with one — her — Jon challenges her: what about all the other people who think they’re right?

“They don’t get a choice,” Dany says. And this forces Jon to make the biggest choice of all.

This theme of choice also calls back to the pilot episode’s two most famous maxims:

First, Ned Stark taught his sons that “the man who passes the sentence should swing the sword,” imbuing each of them with a moral code of responsibility — one that Jon would ultimately need to draw on when he passed his own sentence on Daenerys’s fitness to rule.

Then, just before Jaime Lannister pushed Bran out the window and set the wheels of the show’s plot in motion, he attempted to outsource his responsibility for that action: “The things I do for love,” he shrugged.

Yes, Jaime, the things we do for love… but, as Jon Snow knows all too well, those things we do are still our choice.

What Unites Us?

When Tyrion is asked who he thinks should be king, he responds with a monologue about the only thing that truly unites people: not armies or politics, but stories.

Now, it may be self-serving for a writer to assert that stories are what make us “us,” but he’s also not wrong. Especially not within the context of one of the biggest and most-watched TV shows in history, based on a book series that’s beloved around the world.

Stories give us a shared culture. They help us find our people, our tribe. They provide us with ideals to aspire to, lessons to guide us, and cautionary tales to avoid. In the case of prophecies, they can often be galvanizing yet misleading. And, as Tyrion astutely notes, the ultimate power of a story is (for better and for worse) notoriously hard to break.

Of all our stories, history is the only one that never ends; it just changes, depending on who’s writing it.

They say history is written by the winners — or at least the survivors. We see the truth of that adage in this episode, when Ser Brienne of Tarth, newly promoted to head of the Kingsguard, sits down to finish Jaime Lannister’s story in the White Book that records the history of each member of the Kingsguard. Had the job fallen to anyone else, very different words may have been written. But Brienne, who loved and respected Jaime despite his flaws, writes her own version of his very sordid truth.

In the official record, Jaime didn’t threaten to murder every man, woman and child in Riverrun; he “took Riverrun from the Tully rebels, without loss of life.” He didn’t slaughter his former allies the Tyrells and then foolishly charge a dragon head-on; he “outwitted the Targaryen forces to seize Highgarden” and “fought at the Battle of the Goldroad bravely, narrowly escaping death by dragonfire.” He didn’t abdicate his duty to the throne when Cersei forbade him to ride north; he “pledged himself to the forces of men and rode north to join them at Winterfell, alone; faced the Army of the Dead, and defended the castle against impossible odds until the defeat of the Night King.” And he didn’t reject a future of peace and love with Brienne in order to return to Cersei’s side when Daenerys attacked; he “died protecting his Queen.”

May we all be so fortunate as to be so well-remembered despite our mistakes, and to be so forgiving in our remembrances of others.

It’s also a bittersweet irony that Tyrion — admittedly Martin’s favorite character and his unofficial mouthpiece throughout the story, the character who has architected so many of the show’s highs and lows — finds that he has ultimately been entirely left out of the official history of the events, which Samwell Tarly has dubbed “A Song of Ice and Fire.”

This slight serves as the audience’s reminder that, as Varys knew: “Power resides where men believe it resides. It’s a trick. A shadow on the wall. And a very small man can cast a very large shadow.”

Tyrion’s name, like the names of Davos, Jorah, Missandei, Melisandre, Littlefinger, and even Varys himself — and like the names of the powerbrokers who pull the strings behind the scenes of our own real-world political battles — will likely be lost to time… but their shadows will live on long after their own story ends.

BONUS: The Lone Wolf Dies, But…

As we were discussing how we felt about the last episode of Game of Thrones, my friend Maura pointed out something I hadn’t noticed: “I like how the Starks all end up becoming their direwolves.”

Robb was fast and powerful, but his rule was impermanent — a Grey Wind.

Arya grows up to be a free-spirited warrior like Nymeria.

Bran grows up to become the king who will lead his people into a bright new age — Summer, the opposite of winter.

Sansa grows up to be a Lady.

And Jon Snow, ever the outlier, heads north to become a Ghost.

More Game of Thrones Posts

How Game of Thrones Uses Scene Structure to Reveal Character and Theme

What Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead Can Teach Us About Modern Storytelling

0 Comments