I was recently playing a 20 year-old video game, and it taught me a critical lesson for living a better life.

Let me explain how this game works and you’ll see what I mean.

Heroes of Might & Magic III (or HMM3) is one of my favorite games of all-time. It’s a turn-based PC strategy game in which players control “heroes” (or generals) and “towns” (or revenue streams). The goal? Dominating the map by eliminating all of your competitors.

Defeating your enemies is accomplished by seizing all of their towns, which ends their ability to produce cash and hire new heroes. If a player controls zero towns for a week straight, they’re removed from the game. So, the win condition is simple enough.

But overtaking enemy towns isn’t easy. They’re usually fortified by defenses, armies, and opposing heroes. This means your own forces must be strong enough to withstand and overcome the town’s defenses that are designed to slow your assault and sap your strength, and then have enough power left to defeat the opposing army on the other side of the wall.

While I’ve played this game for two decades, only recently did I realize I was playing the game wrong — and the lesson I learned here also applies to real life.

Where I Went Wrong (and You Where You Probably Do, Too)

The real conflict in HMM3 isn’t between you and your opponents. It’s the age-old battle of resources vs. time. How quickly and efficiently can you amass an army that’s capable of achieving the necessary objectives? Each player tries to solve that puzzle, but their main resistance isn’t coming from other players: their main resistance is their own doubt about how capable they really are.

You ask yourself this same question whenever you launch a new business: how quickly can you create a minimum viable product that will start earning the revenue and attention you need in order to grow, improve, and defend yourself from competition?

You’re also doing the same thing when you date: what’s the minimum viable presentation you need to make in order to attract the attention of a possible mate? Then, how can you use this initial influx of positive investment to grow, improve, and defend your bond from competition? (It’s funny how love and money basically work the same way — they’re both external validators of how we see ourselves — but that’s a topic for another day.)

As I played HMM3, I noticed something about my play style that correlates to the way I live my life: in most cases, I was overpreparing for risk.

Like, drastically.

I spent so much time and money building armies and gaining experience that by the time my main hero did roll out to explore the map, s/he was essentially unstoppable. While this might sound like a safe and solid strategy, it’s actually a bad move for two reasons.

1. I could have won faster if I’d just trusted my own experience.

The longer you play any game, the better you get. And, in most cases, your experience matters more than the raw materials you have to throw at a problem.

In the case of storming enemy towns, I realized I didn’t need a massive army; what I needed was an army that was just good enough to win without suffering cataclysmic casualties that would require me to stop and replenish my entire force before moving to the next town. By being able to move faster and use my accumulated experience to win more battles — even pitched battles that, on paper, I should have lost due to the other side’s stronger army — I found that I was able to overtake towns more quickly with smaller armies, defeating opponents with strategy rather than waiting to crush them with my massive endgame force. This ultimately led to much faster finish times and higher overall scores.

2. Being overpowered is boooooooooring.

Commanding a nearly-undefeatable army can be lot of fun for the first few battles. But by the 30th, or the 300th, it’s just a repetitive slog with no deeper emotion or purpose.

When you can’t lose, you don’t get to experience the thrill of a near-loss that you masterfully salvage in the final moments, or the difficult lesson you learn during a near-win that fell short, which leaves you with a renewed itch to keep fighting and improving.

Instead, you go on autopilot. You plateau. You play it safe.

You stop growing.

And once you stop growing, you’re only playing to not lose… which means, in a way, you already lost.

Why We All Need to Take Bigger Risks

First, let’s be clear about something: taking risks satisfies a biological need.

When we take risks, we get a jolt of dopamine. Science has proven that different people need different levels of dopamine to feel satisfied, so that guy who jumps out of a plane with no backup parachute probably needs more of a dopamine spike to get through his day than you do.

But everyone needs to take risks or else their systems become stagnant. When we play it safe, we stop learning, adapting, processing new information, or encountering new stimuli that require us to find new ways to solve problems. We also become sedentary, which is a massive physical health risk.

In other words, our comfort zones are where we go to die.

And yet, most people will only take a risk if they’re so overprepared that they can’t possibly lose.

This is a mistake, and it’s holding you back from living the life you really want.

From Casablanca to Steve Jobs, we romanticize the risk-taking mavericks and rule-breaking antiheroes in history and pop culture. We like to think we’d behave the same way if we had the chance… and yet we already squander the opportunity to do this every day.

For example…

You won’t invest in Company X unless you’re guaranteed to make your money back.

You won’t start a new venture unless you have so massive a nest egg that a complete collapse won’t hurt.

You won’t travel to a new country unless you feel conversably confident in their language.

You won’t ask someone out unless you’re receiving multiple signs that they’re interested in you first.

You won’t volunteer for a new opportunity unless its skill set is already in your wheelhouse.

In short: most people won’t do anything if there’s a sizable chance that they might not succeed.

We need to fix this.

Don’t Worry: Avoiding Risk Is Totally Normal

As James Clear notes, we excel at talking ourselves out of taking chances, so we content ourselves with the appearance of effort rather than actually taking action.

We’re also terrible at understanding what a real risk actually looks like.

As Margie Warrell notes in her books like Brave and Stop Playing Safe, humans tend to drastically overestimate their odds of failure, which prevents us from taking the risks that could improve our lives. You see this born out by studies that show some people believe the world in the worst condition ever, even though global quality of life is actually better than it’s ever been before.

So, here’s the problem in a nutshell: humans are incredibly reluctant to take risks… and yet nearly every innovation, influential work of art, and meaningful connection we experience happens outside of our comfort zones, when our risk of failure, misunderstanding, embarrassment, and defeat seems high.

Given the known upsides to successfully navigating risk, why, then, are we so risk-averse?

Why do we pursue the safety of known paths, rather than the thrill of leaping across chasms?

Why do we choose to maintain boring routines instead of exploring new methods?

What do we have to lose?

Rationally, you know that if you lose money, you can always make more. If you get embarrassed, you can always recover. If you lose someone’s respect, you can always earn it back (or, if you can’t, fuck ‘em). And if you lose time, you’re still learning from the experience of not reaching your intended goal, so it’s really not a loss; it’s just a different product than you were pursuing.

Rationally, we know that we’re far more adaptable than we give ourselves credit for.

So, again: why are we so risk-averse?

Ultimately, I think it comes down to the story we tell ourself about winning.

We Think Success Is for Other People

We perpetuate the myth that victory is all that matters.

We want to celebrate achievements without acknowledging the process of getting there.

We want to believe in genius without believing in work.

Therefore, when we do win, one of two negative things usually happens.

Sometimes we (mistakenly) believe we won because we’re special. This is understandable due to our cultural obsession with winners. We devour endless retellings of “the hero’s journey” that lionizes the idea of “the chosen one,” and we believe that this is how victories are achieved: by being the only one true right person who could have done what we did.

Sometimes we (mistakenly) believe we won completely at random. Deep down we suspect that success is the product of such an unknowable and uncontrollable series of variables, rather than a product of skill and persistence, that we’re just glad we were in the right place at the right time to find this particular golden ticket.

In either case, our victory has now defined how others see us, and how we see ourselves… and we’re terrified of changing that story.

If we think we won because we’re special, we’re now afraid to put ourselves in a situation where we could reveal that we’re actually not special at all. This is why companies at the top of a market have so much trouble innovating or evolving. Change involves risk, and a high likelihood of failure, so those darlings of the industry are petrified of racking up a few losses that might make them look mortal. (Ironically, if they don’t innovate or evolve — if all they do is play it safe — they eventually WILL be overtaken by the smaller, scrappier risk-takers who see themselves as underdogs, because their competitors’ self-image allows for the “take as many risks as you need to get to the top” approach that the company at the top can no longer stomach.)

If we think we won because life is a roulette wheel, we undervalue the factors that actually did play into our success — things like experience, expertise, strategy, precision, efficiency, attention to detail, and communication. In that case, we may take risks we have no business taking because we truly don’t understand the process — and, thus, any future failure will validate our “oh well, life is random” POV — and we won’t be able to capitalize on the things that we or our team actually do well.

So, What’s the Cure for These Mindsets?

How do we stop overpreparing for risk, or avoiding it altogether in favor of clinging to safety?

We increase the one ability that helps us weather failure:

Resilience.

If you’re resilient, you trust yourself to bounce back from a failure. You know it may take time, effort, money, and luck to get back to a point where you can feel competitive again, but you also trust that you can get yourself back there.

If you’re resilient, you’re confident in your abilities while being humble about the variables that occasionally work out in your favor. You know that one of your competitors could win this round, but you trust that you could win the next one if given another chance. Likewise, you know that you might win this round, but you respect that your competition — or life’s general ups and downs — might win the next round, and that doesn’t worry you.

if you’re resilient, you’re excited about learning. You appreciate the act of moving toward a goal for its own sake, and not just as a component of a winner-take-all worldview. Likewise, you realize that winning and losing are only temporary pause points on a longer continuum of lifelong learning, not destinations unto themselves at which point all learning and growth stops.

If you’re resilient, you don’t allow yourself to be defined by any one experience, win or lose.

If you’re resilient, you’re excited about tomorrow, not afraid of it no longer being today.

From my point of view, increasing your own personal resilience is the greatest investment you can make in yourself every day. Becoming resilient is a matter of practice, and there’s plenty of science about what methods work. But what it all comes down to is reframing the stories we tell ourselves about how we learn and what we value.

Taking risks is the only way we can grow.

So stop judging yourself only by your wins and losses, because they’re all temporary.

Stop overpreparing.

Start taking more risks, and learn as you go.

Start asking for help, and inviting others to share your success.

Get better at bouncing back, until you’re no longer worried about falling.

Make your life the singularly thrilling adventure it can be, rather than only taking the bets you know you can’t lose.

That’s how you build a business, create a work of art, or live a life that just might change the world.

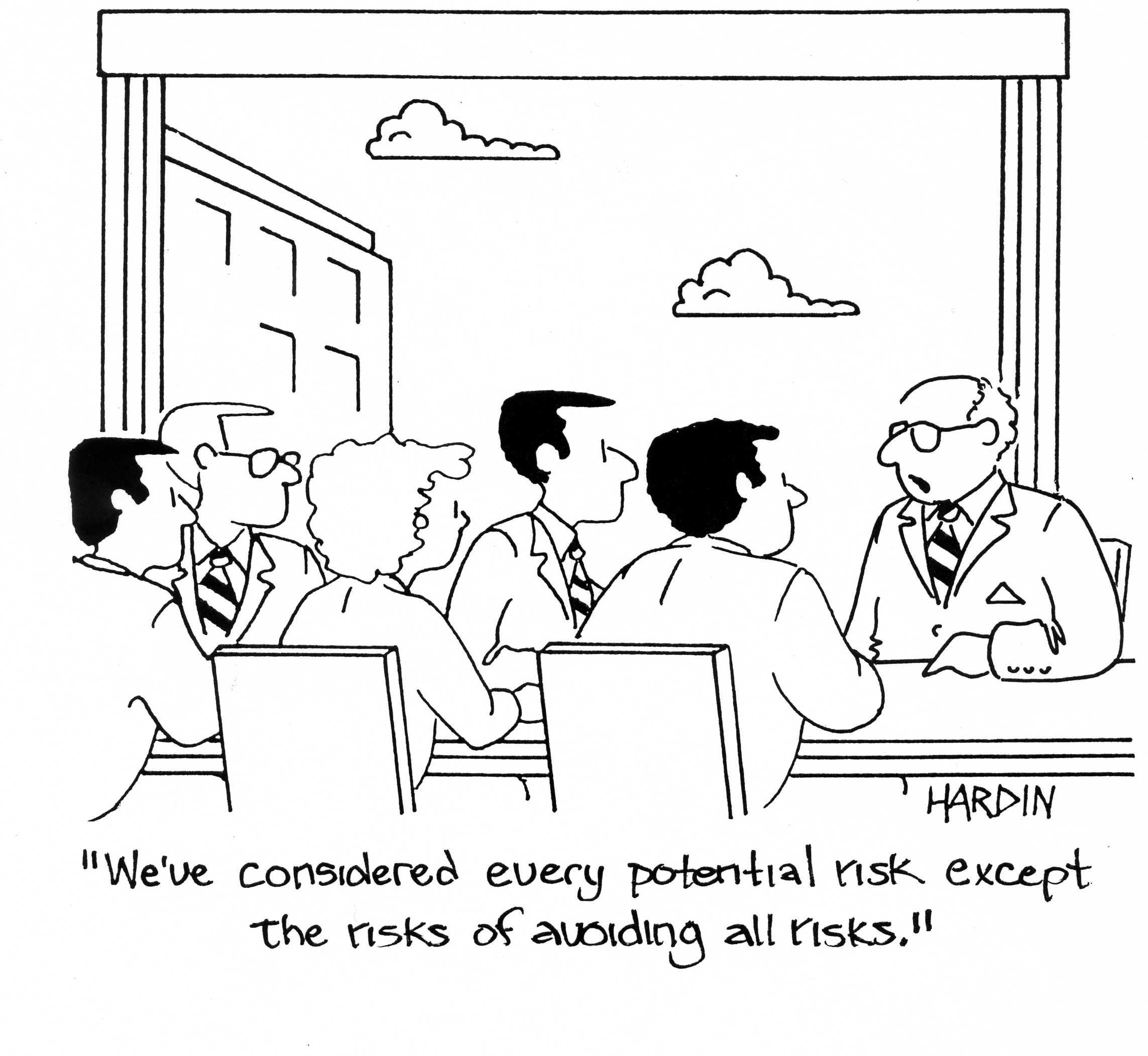

“Oregon Vacation” image by Chris Weber and “Time Is Money” image by Jon Vonica, both via Flickr Creative Commons. // “Risk Avoidance” cartoon by Pat Hardin and “Iceberg of Success” cartoon by Sylvia Duckworth

If You Liked This Post

… then you may also enjoy this post about how to feel like you’re doing “enough,” or this post about how to find a life goal that’s actually worth pursuing.

0 Comments