Yesterday, Harry Anderson died.

Best known as Judge Harry Stone on Night Court, Anderson’s homespun blend of magic and comedy was a formative influence for many Gen-X and Millennial comedians. On Monday night, his fans and colleagues of all ages took to Twitter to share their memories of Anderson.

As they did, I noticed a recurring theme: “but.”

Many fans felt like they had to qualify their love of Anderson’s work, or of Night Court in general, with caveats.

“I watched this with my parents when I was growing up” was a common code for “I didn’t know any better at the time.” Another proclaimed, “no shame, no embarrassment, I loved Harry Stone” — as if they were preempting the judgment they knew was coming from people who viewed Night Court as something less than a high-quality work of art.

And that’s why I think we need to reconsider how we talk about media.

In Praise of “Bad” Art

In a recent post on Collider, critic Matt Goldberg suggested that good movies are overrated.

Clickbait title aside, he has an extremely valid point.

Goldberg’s concern is that many good ideas, concepts, performances, set pieces, etc., get buried in “bad” films. By overlooking these “bad” movies (or “bad” TV shows, books, songs, etc.), we miss out on all those jewels in the murk.

I can corroborate this claim firsthand.

Back in 2014, I committed myself to watching one new movie in theaters every week.

As you can imagine, there weren’t 52 movies I was dying to see that year, which meant I sometimes had to drag myself to see something I absolutely would have skipped otherwise.

Guess what: it turns out that some of my favorite films from that year are movies I would have skipped if I hadn’t forced myself to go see them. (Chief among them was Edge of Tomorrow, the Tom Cruise-Emily Blunt sci-fi video game riff that’s now been rebranded as Live. Die. Repeat.)

But even some of the movies I disliked that year still had some amazing moments or ideas that I still think about even now.

Transformers: Age of Extinction is a glorious and almost completely unfulfilling clusterfuck of a movie… that’s also gorgeously shot and features an iconic Stanley Tucci performance you won’t find anywhere else. It also made me think more about how masculinity is portrayed on film than any other recent movie.

Tammy won’t be remembered as one of Melissa McCarthy’s better movies… but her character is also a type that we hardly ever see on film: a female fuckup who isn’t glamorized into redemption, but who’s simply allowed to just… be. And by doing so, she connects with a super down-to-earth Mark Duplass (who, incidentally, gave the best speech I heard at 2015’s SXSW).

And no one should lament having missed Cameron Diaz and Jason Segel in Sex Tape. But the few of us who saw it probably spent more time thinking about the pressures and expectations of our sex lives, the commodification and artificial shame ascribed to porn, and the manic comic stylings of Ellie Kemper than we ever would have otherwise.

None of these films are classics by any stretch. Most of them aren’t even arguably “good.”

But that’s the whole point: there’s still good in “bad” art.

This is why I’m reluctant to openly deride a movie or TV show, because I know someone probably loves it and found something inspiring in it, something potentially life-changing. And who am I to tell them their POV is invalid?

If you think Netflix’s Bright is the best movie you’ve ever watched, I can disagree with you all day and it won’t diminish your enjoyment of the film. But it might stop you from making something of your own, or from talking about what you love in a way that inspires others to do the same. And that, not the film’s questionable world-building and ethos, would be the real shame.

Which brings me back to Night Court.

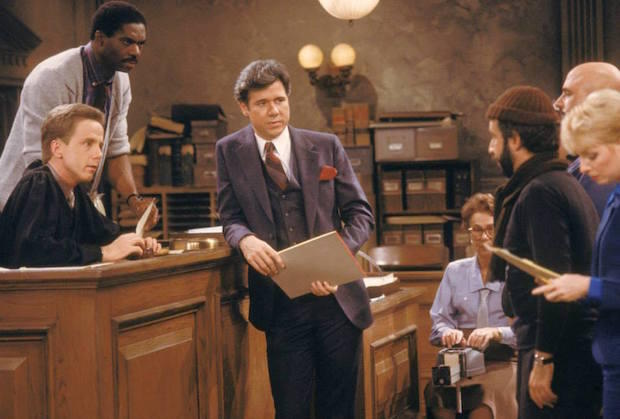

The Emmy-Winning Guilty Pleasure of Night Court

When you think of Must See TV on NBC, you have to think back to where it all started.

In the mid-1980s, NBC’s Thursday night primetime lineup featured four all-time great sitcoms: The Cosby Show at 8, Family Ties at 8:30, Cheers at 9, and Night Court at 9:30.

Those first three shows are bona fide TV classics, inarguable hall-of-famers. Books are written about them, classes are taught on them, and every TV-loving family in America will happily share their memories of watching Cliff and Clair, Alex and Mallory, and Sam and Diane.

But ask them about Night Court and you’ll hear a different phrase:

“Guilty pleasure.”

It’s the same term we use for pop music we like despite ourselves, movies we hate to admit we enjoyed, and books we only read “because everybody else was doing it, so… you know…”

Why do some people feel obliged to apologize for liking certain art?

I think it’s because we have a lofty idea of what “good” media is supposed to be, and anything that colors outside those lines somehow doesn’t count. It can be good-ish, or occasionally noteworthy, but it doesn’t deserve the same respect as media that’s consistently “good” (or at least aspires to be).

But why is that?

Why is Cheers “good,” but Night Court is derided as “the black sheep of NBC’s sitcom dynasty“?

Both shows had ensemble casts in a “friends from work” environment that covered the comedy gamut from highbrow (Diane Chambers and Dan Fielding) to low (Coach/Woody, Bull).

Both shows had the occasional serious moment to counterpoint the comedy — as when Sam starts drinking again, or Harry talks to God after a hurricane.

And both shows won Emmys while earning huge ratings, both of which are a measure of perceived quality by their peers, critics, and the viewing public.

I think there are four reasons why Night Court and media like it — the “guilty pleasure” category of art — is considered to be “less than” other art whose appreciation is more easily defended.

The Four Ingredients of a Guilty Pleasure

First, while Cheers was grounded in reality (more or less), Night Court was grounded in fantasy.

The “rules” of Night Court were far more open and cartoonish, which implied that it didn’t need to be taken so seriously because it wasn’t asking to be. Night Court was, in many ways, a reprieve from the “very special episode” formula. Even their “special episodes,” like Dan almost dying in a plane crash, were played mostly for laughs.

Second, Night Court was zany.

Not always, and not every character. But by and large, the breadth of its comedy was much broader than that of Cheers, or other comparable sitcoms. Its scope was wider, ranging from traditional setups and payoffs to openly vaudevillian wordplay, puns, and pratfalls.

This broad view was mirrored by its characters. Every ensemble cast has its cartoonish eccentric, its lunkhead, and its paragon of virtue straight man/woman, but the characters at the edges of Cheers would have seemed almost unremarkably normal on Night Court. Meanwhile, it’s almost impossible to imagine Bull as a regular customer in Cheers. Their worlds don’t have the same limits.

Third, Night Court was openly horny.

The show didn’t just dance around taboo topics like sex and lust; it wove them directly into the narrative. Nearly every Dan Fielding subplot features actor John Larroquette lusting after that week’s nubile object of desire. (For this, and for many other skills, Larroquette won four Emmys in a row.) Years before Seinfeld and Will & Grace took things to a whole new level, Night Court was already pushing the TV censors’ envelope to see just how much it could get away with in primetime.

Fourth — and I think this is the sticking point — Night Court didn’t apologize for any of this.

It’s one thing for a mostly-serious show to have the occasional zany moment, or to have a lone character who exemplifies its most eccentric abnormalities, or to throw in the occasional blue joke as an eyebrow-raiser. Night Court did all of this in just about every scene, to the point that it almost became self-parody — and it never once asked its audience to think less of it for doing so.

And this, I think, is what truly separates the media we think of as “good” from the media we feel obliged to classify as a guilty pleasure: we have an invisible definition of “quality” that we expect our media itself to feel guilty about not meeting, which means we compel ourselves to apologize for enjoying it “despite its shortcomings.”

And that should stop.

Our Appreciation of Art Is Imbalanced

We’ve been trained to value certain kinds of art more highly than others.

We perpetually reward high-minded drama over slapstick comedy because drama seems hard and generates deep feelings, while comedy seems easy and generates laughter. Ask any comedian how “easy” comedy is and they’ll laugh you right out of the room, and yet there’s a reason why even the best comedians can’t win Oscars until they act in dramas: as a culture, we overvalue seriousness.

We rush to excuse the media we like as being somehow “better” than the “trappings” of their genre, so we can justify concepts like “the golden age of TV.” As if Game of Thrones isn’t just an illogical soap opera with dragons, or The Shape of Water isn’t the PG-13 version of a horny tween’s take on socially woke monster movies.

In doing so, we honor tragedy over comedy, and we prize intellect over joy.

What’s missing from this equation is the fact that the absence of comedy and joy are what make tragedies feel so tragic in the first place.

And what else gets overlooked is the difficulty in blending so many disparate tones, textures, and expectations together to create a comedy pastiche that manages to please everyone, at different levels, all at once.

Which, when you think about it, means we should probably step back and re-evaluate why we insist on celebrating drama — which often evokes universal feelings — over comedy, which requires a higher level of skill, specificity, and relatability to succeed.

At the very least, maybe it’s time we stop apologizing for loving what we love, and start celebrating the art and media that moves us not just in large ways, but also in tiny moments of buried genius.

If You Liked This Post…

You should subscribe to my newsletter so you’ll never miss a post. (I send it weekly-ish.)

Also, you may enjoy why Stranger Things 2 has a near-perfect first episode, or why Black Sails has one of the best main characters in TV history.

Why Black Sails Has One of the Best Main Characters in TV History

1 Comment

Naked Truth of Markie Post – Measurements, Net Worth, Wiki · June 4, 2020 at 1:17 am

[…] found regular work in the game show “The $10,000 Pyramid”, and was also cast as a regular in “Night Court”, playing the character Christine Sullivan. The sitcom follows the story of an unorthodox judge […]