As much as we celebrate change, there’s an ugly truth to society:

Our systems tend to resist most attempts to change them.

That’s not necessarily because the people who power those systems are assholes. (Although, yes, some people are just assholes. And when assholes get a little power, their terribleness tends to multiply.)

Broadly speaking, most systems remain intact because (at best) they work, and (at worst) the act of changing them is more effort than anyone can prove is worthwhile.

This isn’t because people want broken systems; they just don’t want to have to go through the effort of changing if that change isn’t guaranteed to be tangibly better for them.

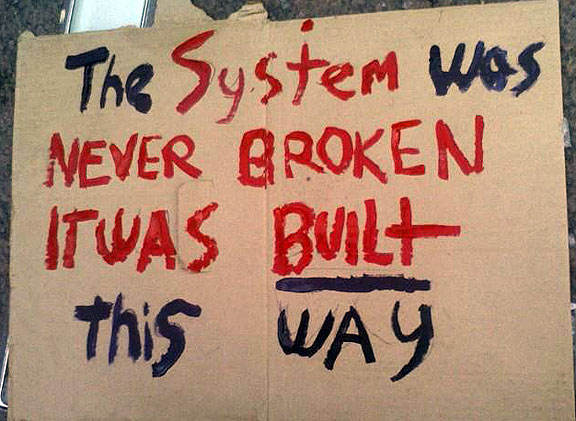

And yet, from our seemingly endless examples of police brutality to our institutionalized education problems, there’s no shortage of obvious systemic flaws.

“Our police department is racist.”

“Our political system is doomed.”

“Our school system is a joke.”

“Our economy is broken.”

“Hollywood is sexist…”

And on, and on…

Now, maybe these systems don’t seem flawed to you. (If not, congratulations, you’re probably a straight white guy with money.) But it’s not hard to find data, conventional wisdom, and firsthand accounts that explain — both logically and emotionally — how and why these systems are broken for large percentages of the population, and why society as a whole — yes, even straight white guys with money! — would be better off if these broken systems were fixed.

So why is it so hard to change them?

To figure this out, let’s start with a bus schedule from hell.

Remember When Chile Ruined Everyone’s Quality of Life?

Public transportation is usually near the bottom of anyone’s “efficient systems” list, because it requires human beings to make optimal decisions on behalf of large groups of strangers with ever-changing needs.

But as the citizens of Santiago learned, sometimes even the best of intentions can actually make things worse.

When the city rolled out its Transantiago program in 2007, it became a case study in how not to fix a public transit system. Poor communication, bad design, inadequate routes, overcrowding, and operators who were given incentives that didn’t align with the needs of their passengers — all contributed to a $250M USD project spinning further and further out of control.

And yet, it’s illogical to believe that anyone wanted to make the situation worse than it already was. (And it was bad.)

So why did the new system fail?

Because the people, the processes, and the results were misaligned. And this is in a situation where everyone involved stood to benefit from system-wide improvements. So even in a case where all participants win… sometimes everyone still loses.

But can’t we do better?

Yes…

… but first we need to understand what exactly it is that we’re trying to change.

It’s Alive… IT’S ALIVE!

When we talk about systems, it may feel like we’re discussing something intangible — an infallible belief, or a collective illusion that can’t be broken. But that’s not true.

A system is really just people following a set of processes that achieve a desired result.

To break any system down into its components, you have:

- People

- Processes

- Results

If you change any one of those elements, you affect the system. (But that can be hard.) And if you change all three of those elements, you replace the old system with a new system. (That’s even harder.)

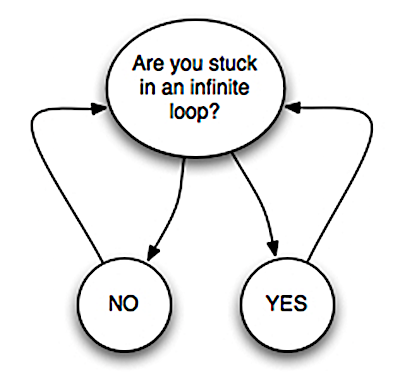

The problem is, a system is inherently difficult to change.

That’s because as long as a system is capable of achieving the desired result, that system is considered to be “good enough” by the people who participate in, program, and enforce it.

To consider changing it, those people would need to evaluate their system, consider alternative processes and results, and decide that the efforts necessary to change their system will result in demonstrably better results than what they’re already getting.

This doesn’t happen easily.

There’s also an opportunity cost, or a risk, associated with even the noblest attempts to change a system.

Any effort to improve that system could fail, and that might be considered a waste of time, effort, and resources by the participants and programmers — especially compared to the likely outcome if all their time, effort, and resources hadn’t been diverted from what was already “working” well enough. (This explains why your day job is so slow to adapt to… well, anything.)

This failure to effect change may also impact the participants’ attitudes toward future attempts to improve their system. If attempted change already failed once, trying again might seem foolhardy.

This is why participants in any system often feel it’s better to trust the devil you know (a flawed but effective system) than the devil you don’t (a different system) because at least you know the existing system “works.”

So… how do you actually change a system?

Get Real

First, let’s start with a basic premise: we’re all humans. (If you’re a bot, please enjoy this instead.)

As evolved as we may be, humans still operate from two primary motivation sources: logic and emotion.

Logically…

- We want to be sensible

- We want to be efficient

- We want to survive

Emotionally…

- We want to be happy

- We want to be loved

- We want to be safe

Any system we create is meant to solve one of those problems. And as long as it solves one of those problems without making one of the other problems worse, that system will last.

For example, do we want to be sensible? Then we establish systems of logic, reason, language, morality, justice, politics, economics, and other ways to measure our actions and outcomes according to a mutually agreed-upon (by the majority of the participants) concept of sensibility.

If someone robs, kills, or cheats within that system, its rules are intended to re-establish sensibility through morality, justice, etc., so that the system stabilizes itself, on average. (Obviously, no system is perfect for all participants.) But if the outcomes are incompatible with most participants’ expectations of the system — e.g., offenders receive no penalty, or the penalties are too high or low compared to the perceived transgressions — then that system will begin to fail because its processes are not delivering its peoples’ desired outcomes.

But just like no one in power will relinquish power unless doing so would improve his own life, no system will change itself unless its own participants realize that a changed system would improve their own lives.

And that means to change a system, you need to change people.

Which, as you probably know, is hard as hell.

Mirror, Mirror, on the Wall…

Are you a racist? Of course not!

At least, not as far as you’re concerned.

The truth is, even if you behave in a manner that others would consider to be racist (or sexist, homophobic, etc.), you probably don’t think you’re a racist. You think you’re behaving appropriately, and that other people have a problem with a system you believe is completely equitable because it’s delivering results that you have no problem with. And if someone else has a problem with those results, that’s their problem.

Now, imagine you’re of a different skin tone or gender.

Would your system still seem equitable to you? Actually, it probably would, because few of us really have any idea what it’s like to experience life as someone else does. And because we don’t want to believe that our chosen system is inherently flawed — or that we’re knowingly behaving in a way that literally makes other people’s lives worse — we convince ourselves that even if we were someone else, we’d be just as successful within our system as we are now, because we believe our voluntarily engaged systems are meritocracies that we can win — even when multiple data prove otherwise.

This is why trying to convince other people that they need to change their system on behalf of someone else is a losing proposition: because what you’re really saying is, “reduce your power so I can benefit.” And even if logic and emotion both justify your position, the participants in that system are going to have trouble believing the implication that they’ll be better off if you are.

After all, they’re OK right now. If they change their system, they might not be as OK, and they’re afraid of being less OK. They don’t want to have to learn a new system, and they definitely don’t want to have to process the shift in identity that comes with being less OK. Plus, if you become more OK as a result of that change, they’re going to perceive that shift as you profiting at their expense. And no matter how noble or altruistic that change was intended to be, it’s hard to convince a human that him being less OK is good for him.

So, how do you convince the people within a system that their system should change?

Aw, C’mon, Man…

Generally speaking, here’s what won’t work:

- “It makes sense.”

- “It’s the right thing to do.”

- “It would help [someone who isn’t them].”

- “The existing system is outdated.”

- “Other people are changing their system, so why aren’t we?”

Those arguments may be emotionally compelling or logically true, but they don’t address the key obstacle: they don’t explain how a new system would be better for the participants of the existing system.

But wait! Wait! I can hear you all now:

“Why should we care if a system is better for the people who are already benefiting from it? If it’s broken, we need to blow it up and start all over!”

On paper, sure, that may seem logical.

In reality, not so much — for two reasons.

First, blowing up a system creates a vacuum in which no one is solving the original problem anymore. If your police department, school system, or business isn’t producing the desired results (a safe and happy community, well-educated students, or acceptable profits, respectively), then blowing up those systems creates temporary anarchy in which no one is reliably providing even a broken service.

But isn’t that better than putting up with a broken service? In some cases, maybe… until you factor in reason number two:

Once that vacuum exists, all parties with an interest in establishing a new system to solve this currently unserved problem are now racing each other to establish a new dominant system. And who’s most likely to win that race? The people with the most resources to expend — which, in most cases, are the people who were already profiting from the last system.

Am I saying that an insurgent system can’t topple an existing system, establish its own dominance, and better serve its constituents? No. It happens all the time. (See: military coups, disruptive technologies, and people who get happily remarried after a divorce.)

But those successes come with the added burden of needing to defend themselves against the rulers they deposed. (Or at least the angry gossip of jilted spouses.)

Is there a better way to change a system than blowing it up?

Sure: convince and convert.

Four Tactics for Proactively Changing a System

If the arguments above won’t work, which ones do? Ones that make the existing system better for everyone.

- “Here’s how we can (all) save more time by becoming more efficient.”

- “Here’s how we can (all) make more profit by changing a process.”

- “Here’s how our (mutual) health can improve by changing our habits.”

- “Here’s how killing fewer unarmed citizens makes (all) our lives better.”

Granted, these arguments don’t work every time. People can be hard to persuade (although there are proven tips that help). But that’s the key:

Changing people takes time.

Unfortunately, the immediacy of the Internet means we want to see wrongs righted as quickly as those wrongs become news. But while a headline can travel around the world in seconds, changing the systems responsible for those headlines takes a little longer.

A racist or sexist or calcified thinker doesn’t suddenly become inclusive and open-minded overnight. Even if he consciously admits he wants to change, he’s still fighting a lifetime of inherent biases, learned behaviors, and Pavlovian responses to stimuli. No amount of logic or emotion can undo that in a day.

Ditto the company that realizes it needs to evolve in order to remain competitive.

Or the couple who sees the cliff’s edge of their relationship and knows they have to change their behavior in order to avoid it.

A couch potato won’t wake up tomorrow and run a marathon. He starts by trying a salad, realizing that salad isn’t terrible, paying attention to how he feels after eating a salad vs. a carton of ice cream, and consciously choosing to eat a few more salads and a few less potato chips, week after week, until he wakes up one day and notices a demonstrable change in his appearance, his energy, and how he feels about himself.

He’s not an idiot. He knows he should be eating better and exercising.

But he has to want to change his behavior.

In order to change his own behavior and belief system, he has to create better habits and stick to them. And that takes willpower, which can be astoundingly difficult to cultivate. (Some studies claim we even have a finite amount of willpower. You can learn more about how to boost yours here.)

Because systems are comprised of people, those people have to want to change. And the benefits they see from behaving differently have to be demonstrably better for them than what they’re already doing. Otherwise, they’re going to resist that change, and the flawed system continues.

(And it doesn’t help that most people don’t communicate clearly in the first place.)

If a System Won’t Change Voluntarily, Can’t I Just Defeat It?

Sure. And you don’t even need a military coup to do it. Instead…

- Join the system and create change from within (which can take a long time)

- Beat the system at its own game (which can take a lot of time, effort, and resources)

- Identify a structural weakness within the system and build your own system that meets those same needs more efficiently (which requires you to outmaneuver, outrace, and out-defend your system against the dying gasps of the old one)

None of these routes are easy, but then, neither is convincing someone else to change. But your odds of convincing them to change are much greater if you’re…

- already in their system (seen as a peer or cohort)

- exploiting their own processes (thus proving your own competence and, therefore, earning the respect of the old system)

- proving that there’s a better system by achieving concrete results through alternative processes (rather than just theory)

Note that doing any of these doesn’t guarantee that you’ll be welcomed into the old system, or that the old system will happily change to accommodate you. But results have a way proving a point that all noble theories and good intentions in the world just can’t.

A Word About Victimhood

Remember when I said that systems can seem intangible — like an invisible force that just “exists”? We all have a tendency to believe those systems are out to get us, or that the system itself is the sole reason why we’re not happy or satisfied.

“My job wants me to fail.”

“My family wants me to be unfulfilled.”

“My government wants me to be miserable.”

In no world do those statements make logical sense, so we’d never say them out loud. But we do say things like “my life would be so much better if my job / family / school / government would just [change].”

That may be true.

But you’re part of that system too.

So even though you’re just one person within that system, you can change. And if you change, the system changes.

“But I’m completely and 100% right and the system is completely broken,” you insist. “Why should I have to be the one who changes?”

Maybe you don’t have to change yourself; maybe you just need to change your approach.

Are your beliefs not coming across clearly? What if you change the way you express them, or the people you express them to?

Is your behavior not leading to your desired results? Maybe you need to lead by example, or try different tactics to achieve those same goals.

However, a little change — even temporarily — may not be a bad thing.

Attempting to understand the system from the opposite point of view will help you see why it behaves the way it does, which could help you find a new thought process that bridges the gap between you and it.

And if that doesn’t work, you can try convincing the system to like you instead. (It worked for Benjamin Franklin.)

When All Else Fails… Prove It

When you’re in a results-based system (which most are) — or when interpersonal politics or personalities seem to be creating a roadblock that you just can’t get around — there’s still a way to get what you need: ask forgiveness, not permission.

If your boss / parent / elected official hasn’t been swayed by your logical or emotional arguments… do what you want to do anyway, and then show them the results.

If you were right, and your methods are proven to achieve a better outcome than the existing system, you’ll have a stronger case for convincing them to implement your approach.

And if they’re more angry that you circumvented their approved process than they are happy about your improved results, now you have two new options: ignore their obstruction and keep achieving your improved results, or quit their system and use your proof to build your own new, competitive system.

But the one thing you don’t want to do is believe that the system is “out to get you.” Because when you think it is, you start to believe that the only way you can achieve your own goals is to completely overwhelm the system — and that takes a level of time, effort, resources, and risk that’s statistically unlikely to succeed.

If anything, the system is probably ignoring you because the people within it just want to get their own jobs done and go home to their families. And as long as they’re achieving the results most people expect, then the system is doing “good enough.”

Don’t agree?

Prove it in a way that they not only can’t argue with, but in a way that makes them wonder why they haven’t been doing it better all along.

If You Like This Post

… then you may also enjoy this post about the 12 tough truths we all need to hear, or this post about how to create incremental change in your own life.

If You Want to Change Your Life, You’ve Got to Start Somewhere

2 Comments

Glen E Quiring · June 24, 2019 at 3:10 pm

Nice job.

12 Tough Truths | Justin Kownacki · July 29, 2015 at 9:22 pm

[…] can easily be gamed and exploited, from finance to politics to education to justice. If you try to “fix” those systems, you’re likely to be defeated or destroyed, because the people in charge of those systems […]